| Monday, February 10, 2003 |

| Mimicry Nation |

My three year old daughter is great at learning by mimicking. She will do things sort of like grownups do it. She'll go through the motions, press the buttons, say the words, and often she'll quickly learn to do things for real. She's recently been practicing jokes, and she's mimicked the rhythm really well, even if the punch line isn't strictly speaking funny. Oh, it is very funny when she does it, no matter what the punch line is. It is a great strategy for a baby or a toddler. Just start faking it till you make it. It is delightful and wonderful and entertaining that it works. My three year old daughter is great at learning by mimicking. She will do things sort of like grownups do it. She'll go through the motions, press the buttons, say the words, and often she'll quickly learn to do things for real. She's recently been practicing jokes, and she's mimicked the rhythm really well, even if the punch line isn't strictly speaking funny. Oh, it is very funny when she does it, no matter what the punch line is. It is a great strategy for a baby or a toddler. Just start faking it till you make it. It is delightful and wonderful and entertaining that it works.

But what starts worrying me is that it also seems to be a pervasive principle in education in schools as well. American schools is what I'm talking about. Their homework and essays often adds up to sounding like you're actually talking about something real and useful, even if you aren't. So, if you can just regurgitate some of the materials you've studied, and put together sentences that look fairly correct, you'll do pretty well. And if the components are mostly right, you'll get a good grade. Nobody pays much attention to whether the things you do actually are useful. I realized some horrible things about education some years ago when it was part of my job to hire computer programmers. I hired a dozen or so programmers over several years. To do that, I had to look through the stacks of thousands of applications we'd gotten, and I needed to interview hundreds of people and pick the ones to hire. And a disturbing picture quickly started forming. Very often, the more advanced a degree the person had in Computer Science, the more hopeless it was to expect them to program anything real. Well, generalizing is dangerous, so let me point out that I'm talking about those who didn't have real jobs as programmers while they were studying, and who didn't spend all their sparetime programming video games. And, don't get me wrong, there are some really useful things on the curriculum in Computer Science, which all programmers really ought to know. What I'm talking about is the people who just went through the college courses and exercises and exams, hoping to be great computer scientists, hoping they'd have a career once they were done. If it were just a Bacherlor's degree, there might be some hope that they could actually program, and that they might apply some of what they learned. If it was a Master's degree, it was probably too late. And the clerk in the store where we bought our computers, he had a Ph.D. in Computer Science, the poor fellow. The point is that here we have some people who've worked hard for years, and they've learned to get things *mostly* right, who've learned that if they get 80% of the questions right, they're doing well. If they can regurgitate what the textbook says, and make their answers look about right, they do well in school. They've been thoroughly trained and validated into doing things that look sort of right, but which aren't. The problem is that in the real world, if you have the job of building something that actually works, as a computer programmer or as an engineer, or you need to do something very precise and important, like surgery, you can't get away with anything much less than 100% right. You might get away with 99.99% right, and the last 0.01% will still haunt you. But if you're several percent off, the bridge will fall down, the patient will die, and your software just won't run. You can't *almost* save an account record and still call it an accounting program. It doesn't matter if you made a good effort and that your notes look good if you amputated the wrong leg. I solved my hiring problem by giving people actual tests that involved solving a problem by writing a program, and I hired the people who wrote a working program. The best programmer I hired was a 19 year old guy fresh out of highschool. The bigger point I'm trying to make is that a large percentage of the human population, even as grownups, are just mimicking what others are doing, regurgitating what they've heard, and trying to look right. And a surprisingly small percentage of people are actually thinking through and figuring out how to make things work. And the horrifying thing is that sometimes whole countries are run by people who're just actors who're kind of winging it and trying to say things that sound about right. And they gather people around them who're good at making things sound like they know what they're talking about. And when they say these things in the media, lots of people will repeat them, and will go around talking about stuff they really have no clue about, but they know how to act as if they do. [ Knowledge | 2003-02-10 21:48 | 6 comments | PermaLink ] More > |

| Creating a Culture of Ideas |

Nice article in Technology Review by Nicholas Negroponte (MIT Media Lab). Nice article in Technology Review by Nicholas Negroponte (MIT Media Lab)." Innovation is inefficient. More often than not, it is undisciplined, contrarian, and iconoclastic; and it nourishes itself with confusion and contradiction. In short, being innovative flies in the face of what almost all parents want for their children, most CEOs want for their companies, and heads of states want for their countries. And innovative people are a pain in the ass. [...]Ah yes, how do we teach people to be awake, to think new thoughts, to see things from different angles ...when we mostly are teaching kids in school to be like everybody else? Negroponte does have a point about the U.S. though. The culture in the United States, at least in some major parts, is highly valuing individual creativity and success, and it is very forgiving about failures. And it values the unique perspectives of children, even if the school system doesn't really reflect it. That is quite different from many other countries, and is a big reason why the U.S. traditionally have produced many more innovations into the world than its population would indicate. [ Knowledge | 2003-02-10 22:46 | 0 comments | PermaLink ] |

| New Energy Device? |

I believe that sooner or later we'll be switching over to totally different energy production devices. Not burning old dinosaurs, but rather drawing a charge from the quantum field, or something along those lines. And there has been no lack of people who seemed to have invented over-unity devices. But either somebody managed to buy off or murder ALL of them, or they didn't really work when put under scrutiny. So it is with some caution that I pass on news about 'free' energy devices. But Stephen Greer of the Disclosure Project has his head screwed on fairly well, and even though he likes being the center of attention, what he presents is normally very solid. A while back he set up a company, Space Energy Access Systems, for the purpose of locating and marketing such devices. And he believes he has something now. See transcript of an interview."It's not very big at all. I picked it up - you can pick it up with one hand. Took it out actually on a sidewalk. This device gathered, very passively, less than one watt of power from the environment - I won't say how it was done, I'm not allowed to at this point - and the machine started up. It generated hundreds of watts of power in usable form. We hooked this up ourselves, so there was no mystery about it. We even selected the things to hook up to this thing. It ran a 300-watt light bulb, a 100-watt light bulb, a stereo and an oscillating fan with an electric motor, all at the same time with literally no artificial manmade input of power."I hope it stands up to further scrutiny. Getting rid of the oil economy would change everything. [ Technology | 2003-02-10 23:05 | 2 comments | PermaLink ] More > |

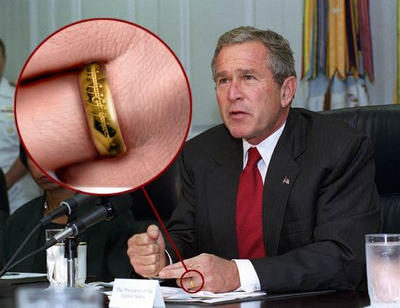

| Frodo has failed, Bush has the ring. |

Long list of some of the best signs from the peace march in Washington D.C. on January 18th:

[ Politics | 2003-02-10 23:34 | 5 comments | PermaLink ] More > |

| Powell's Evidence Refuted |

Informative article at ZNet, doing a good job of analyzing the facts in relation to Colin Powell's U.N. presentation the other day.Only two days after Colin Powell made his presentation to the U.N. Security Council, the evidence he provided is unraveling. Through interviews with experts, intelligence sources, and an examination of the physical evidence, reporters are piecing together facts that refute all of his major claims.In brief, most of it is really old, and the grainy spy pictures are of sites that U.N. inspectors already have gone over recently without finding anything. [ Politics | 2003-02-10 23:59 | 1 comment | PermaLink ] More > |