| A City is not a Tree | 2004-05-23 14:13 8 comments |

by Flemming Funch by Flemming FunchClay Shirky mentions Chris Alexanders excellent essay A City is not a Tree from 1965. Alexander, the architect who invented the idea of Pattern Languages, is always brilliant, and no less so here. Clay says: It’s a moment of disorientation I’ve had a couple of times — you find a great piece of writing, and think “Wow, this is really going to change things!”, only to discover that it is in fact decades old. The clash of historical vertigo with Internet Now is both wonderful and daunting.Semi-lattices? Back to that in a moment. Here are some excerpts from Chris Alexander's essay: Whenever we have a tree structure, it means that within this structure no piece of any unit is ever connected to other units, except through the medium of that unit as a whole.He gives some good examples and indications that the human mind has a tendency, when faced with a complex organization, to re-organize it mentally into non-overlapping units. It is apparently difficult for us to comprehend anything that is overlapping, so we tend to drop most of the richness of complexity in order to be able to think simply.

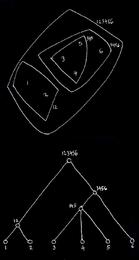

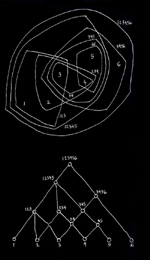

Now, about semilattices versus trees. That gets a little technical, even though he explains it simply.   If you have some sets of elements (numbers are used here) that don't overlap, you can express their relationship in a tree diagram, as you see on the left. A set is a subset of another set, which is maybe a subset of a bigger one, etc. But nothing is a member of two sets. On the right it is different. One number or set of numbers might belong to several different bigger sets. Which can be represented in a diagram that looks like a tree, but which is more complex. That's the semilattice. If you have some sets of elements (numbers are used here) that don't overlap, you can express their relationship in a tree diagram, as you see on the left. A set is a subset of another set, which is maybe a subset of a bigger one, etc. But nothing is a member of two sets. On the right it is different. One number or set of numbers might belong to several different bigger sets. Which can be represented in a diagram that looks like a tree, but which is more complex. That's the semilattice.I agree with Clay that the essays says something important about planned vs grown communities in general, and that this very much applies to information architecture rather than physical cities. But my first thought is then why it only is a semilattice and not a lattice. I can guess that a lattice would be where anything can link to anything else. And in the world of information, like on the web, I'm afraid everything can contain everything else. A "country" can contain all sorts of things, but I might also make "country" be sub-ordinated a bunch of those things. So, where it obviously would be better to use semilattices than trees, we really need to be better able to deal with lattices that have no such restrictions. Lilia talks about it. For me it mainly has to do something with classification. I believe that one of the reasons classifying information is difficult has something to do with the fact that in most cases tree structures are used for classification, so we have to find "unique folder" to put an idea or a document into it. And ideas never belong to "unique folders", they have multiple relations with other ideas, forming a web structure.[...]I have trouble with tree structures too. I have tried a number of mindmapping tools and similar types of programs. Each time I end up being really frustrated because I don't really think like that. My world is not a tree. So my e-mail program and my web bookmarks and my filing system aren't really working for me, because they're all trees. The day before yesterday Lionel and I were doing a little consulting job, helping a marketing directory visualize the network of people he was dealing with. It became really complicated to work out on paper which connections were key. And the mind mapping types of programs I had in mind suggesting would do no good, as they're tree oriented. A program could obviously help, but I don't know of any that fits the bill. We have to figure out how to better deal with multi-dimensional cross-linked information. Sure, on a wiki, or on the web in general, we can freely link anything with anything else. But we quickly lose the sense of any organization. We make a big picture with thousands of lines, showing that, indeed, all sorts of things link to each other. But if we actually want to see useful information, we tend to over-simplify it into some kind of tree, rather than what it really is. I will go as far as saying that it is essential for the further evolution of the human race that we learn how to better relate to multi-dimensional, multi-facetted, inter-connected information and relationships. There has got to be something between a colorful blob and a neat tree diagram. We have to be able to deal with complexity dynamically without having to reduce it no neither a big pile to search in nor a neat hierarchy. Google is great for searching the big pile. XML is great for all sorts of hierarchies. What is in-between? Society has the same problem. The news tells us it is a big confusing blob. Governments usually try to make everything into rigid tree-like hierarchies. In-between we'll have to invent a way of allowing everything to relate to everything else, overlapping as it needs to, without losing track of what is meaningful. Structures that support collective intelligence. |