| How much will you give me for my $20 bill | 2005-04-13 23:06 7 comments |

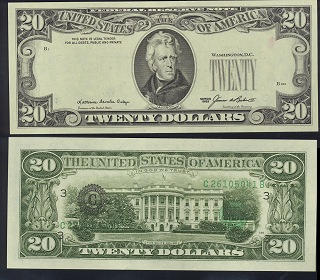

by Flemming Funch by Flemming FunchVarious experiments have been done to try to figure out how people value things and make decisions. Psychologist Max Bazerman says that during the past ten years he has earned more than $17,000 by auctioning $20 bills to his MBA students at Northwestern University. In the course of almost two hundred of his actions, the top two bids never totaled less than $39, and in one instance totaled $407. Now, that's when it is very clear what you get for your money. A 20 dollar bill. Logic should dictate that no reasonable person would bid more than $20 for what obviously is a $20 value. But all sorts of other factors might enter into the calculation. The fun and excitement of the bidding, the prestige of being the winner, the expectation that there might be some kind of valuable hidden bonus, etc. A similar, but somewhat more complex type of auction would be if you're not entirely sure of the value you're betting on. If, say, it is a glass jar full of coins, which you aren't allowed to count. If people make blind bids written down on paper, the average bid will tend to be less than the actual value, as most people are trying to avoid the obvious risk. But some people will over-estimate the actual value, so the winner of the auction would typically be somebody who ends up paying more than the actual value. And then there's the particularly sneaky variant, the Entrapment Gam. Let's say that everybody who bids in an auction must pay the amount of their bid, whether they win or not, but you're allowed to continue over-bidding each other. People will start really low, like 0.50, as most people feel they can waste that. Bidding continues up to around $10 and pauses. Then the people who've bid $8 or $9 must decide whether they'll lose that or they'll continue. It will continue up to $20 when again there's reason for pause. One might realize that one now is likely to lose quite a bit. So maybe if one throws in a few extra dollars and wins, one will lose less, so it might be worth it. And it might go on quite a bit like that, as at each step one must evaluate whether one might avoid a loss by paying a bit more. Even if one ends up paying a lot more for the 20 dollar bill than it was worth. This was apparently the game Mr.Bazerman played with his students. There might be surprisingly many situations in life that are similar to that scenario. Competitive sports, the making of business deals, buying a house, etc. You might have invested a certain amount of time and effort and money, and even if you know you won't get back the equivalent, you might think that just a little more would get you what you're going for and minimize the losses. More here or here. |