Interesting article from 1997 by Howard Bloom about how our reality is formed and manipulated by what we hear, what we remember, what other people seem to believe, etc. Not just that our memories and peer pressure is influencing and coloring how we see the world. No, much more tangible than that. We physically perceive that which we assume we'll perceive and that which we've been conditioned to perceive. I particularly find experiments such as these fascinating: Interesting article from 1997 by Howard Bloom about how our reality is formed and manipulated by what we hear, what we remember, what other people seem to believe, etc. Not just that our memories and peer pressure is influencing and coloring how we see the world. No, much more tangible than that. We physically perceive that which we assume we'll perceive and that which we've been conditioned to perceive. I particularly find experiments such as these fascinating:In the late 1970s, Loftus performed a series of key experiments. In a typical example, she showed college students a moving picture of a traffic accident, then asked after the film, "How fast was the white sports car going when it passed the barn while traveling along the country road." Several days later when witnesses to the film were quizzed about what they'd seen, 17% were sure they'd spied a barn, though there weren't any buildings in the film at all. In a related experiment subjects were shown a collision between a bicycle and an auto driven by a brunette, then afterwards heard questions about the "blond" at the steering wheel. Not only did they remember the non-existent blond vividly, but when they were shown the sequence a second time, they had a hard time believing that it was the same incident they now recalled so graphically. One subject said, "It's really strange because I still have the blond girl's face in my mind and it doesn't correspond to her [pointing to the woman on the videotape]...It was really weird." In visual memory, Loftus concluded that hints leaked to us by fellow humans are more important than the scene whose details actually reach our eyes.[...]

It was 1956 when Solomon Asch published a classic series of experiments in which he and his colleagues showed cards with lines of different lengths to clusters of their students. Two lines were exactly the same size and two were clearly not - the mavericks stuck out like basketball players at a convention for the vertically handicapped. During a typical experimental run, the researchers asked nine volunteers to claim that two badly mismatched lines were actually the same, and that the actual twin was a total misfit. Now came the nefarious part. The researchers ushered a naive student into the room with the collaborators and gave him the impression that the crowd already there knew just as little as he did about what was going on. Then a white-coated psychologist passed the cards around. One by one he asked the pre-drilled shills to announce out loud which lines were alike. Each dutifully declared that two terribly unlike lines were perfect twins. By the time the scientist prodded the unsuspecting newcomer to pronounce judgement, he usually went along with the bogus acclamation of the crowd. Asch ran the experiment over and over again. When he quizzed his victims of peer pressure, it turned out that many had done far more than simply go along to get along. They had actually shaped their perceptions to agree, not with the reality in front of them, but with the consensus of the multitude.[...]

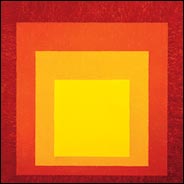

Another experiment indicates just how deeply social suggestion can penetrate the neural mesh through which we think we see hard-and-solid facts. Students with normal color vision were shown blue slides. But one stooge in the room declared the slides were green. Only 32% of the students ended up going along with the vocal but misguided proponent of green vision. Later, however, the subjects were taken aside, shown blue-green slides and asked to rate them for blueness or greenness. Even the students who had refused to see green where there was none in the original experiment showed that the insistent greenies in the room had colored their perceptions. They rated the new slides more green than they would have otherwise. More to the point, when asked to describe the color of the afterimage they saw, the subjects often reported it was red-purple - the hue of an afterimage left by the color green. The words of one determined speaker had penetrated the most intimate sanctums of the eye and brain. So, does that mean we're all just gullible sheep who're walking around in a trance, thinking we see things that aren't really there? Well, to some degree, yes. But we can start becoming conscious of our processes of perception, aware of how realities are generated, and we might actually catch when we're being mislead by words or memories or other abstractions. And we might learn to always expand our sense of reality, reaching beyond the hallucinations generated by our assumptions, beliefs and memories.

[ Patterns | 2003-11-30 07:14 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

Interesting article from 1997 by Howard Bloom about how our reality is formed and manipulated by what we hear, what we remember, what other people seem to believe, etc. Not just that our memories and peer pressure is influencing and coloring how we see the world. No, much more tangible than that. We physically perceive that which we assume we'll perceive and that which we've been conditioned to perceive. I particularly find experiments such as these fascinating:

Interesting article from 1997 by Howard Bloom about how our reality is formed and manipulated by what we hear, what we remember, what other people seem to believe, etc. Not just that our memories and peer pressure is influencing and coloring how we see the world. No, much more tangible than that. We physically perceive that which we assume we'll perceive and that which we've been conditioned to perceive. I particularly find experiments such as these fascinating: Relating to the preceeding posting, there's an article today in the NY Times about Color Cognition, referencing various studies of differences in color perception between people speaking different languages, using different distinctions.

Relating to the preceeding posting, there's an article today in the NY Times about Color Cognition, referencing various studies of differences in color perception between people speaking different languages, using different distinctions.