| Saturday, September 27, 2014 |  |

|

|

|

My wife and I don't always see eye to eye on what it takes to learn something. I will quite readily accept that it might take years of hard work to acquire a particular skill. She will tend to think that an activity better start paying off right away, or it isn't really worth it. We both have some kind of point. Hers being in part that learning might as well be fun and rewarding from the beginning, and there's nothing noble about suffering through a process that won't provide a result before much later. My wife and I don't always see eye to eye on what it takes to learn something. I will quite readily accept that it might take years of hard work to acquire a particular skill. She will tend to think that an activity better start paying off right away, or it isn't really worth it. We both have some kind of point. Hers being in part that learning might as well be fun and rewarding from the beginning, and there's nothing noble about suffering through a process that won't provide a result before much later.

Learning is an important subject to me. I'd love to see better learning methods become available all around. I'm convinced that many things could be learned many times faster and much more thoroughly, if somebody would manage to understand how we learn, and would construct an approach that provided the required input and feedback. Instead, we're usually required to listen to somebody talking and look at some examples of the subject matter, and we're supposed to just learn from that. We do, but usually very slowly.

Until we have this learning robot that I can plug into, which will provide me instant feedback and just the right amount of repetition and variation, and which teaches the core structure of the matter, not all the random blahblah around it, it will take time.

People who've mastered a skill or a subject will know very well what kind of very substantial effort it took to get there. You're not playing classical violin in front of an audience unless you've practiced for years, hours and hours every day. You wouldn't be a stage magician with your own show if you hadn't practiced for thousands of hours to manipulate cards or coins until you do it so well that people don't see what you actually do. You won't be a Ph.D. unless you've digested a mountain of research in your particular field and you know pretty much everything that anybody else has said about it.

People who aren't in the process of mastering anything, or who haven't already done so, would tend to be very unaware of what it takes, and might even be quite likely to ridicule the work. Which is why it often happens out of sight.

My wife and I take dancing classes and enjoy going out dancing. But it is also an arena where our differences show up. In most partner dances, it is quite well known that the leaders and the followers have a quite different journey and different learning curve. The followers mostly focus on relaxing and not trying to anticipate what the leader will do. The leader on the other hand must know what to do, must know the sequence of steps and how to lead them and when to do them. Which obviously he can't do well from day one.

I hate the uncomfortable feeling of being a klutz who doesn't know what to do in a beginner class. Particularly if it seems to be easier for other people. And I'm really not fast at getting something new at first. My approach to keeping up will often be to put in an extra effort, study up on it in my own time, take the beginner class two or three times if I can.

I had started this dance that my wife wasn't yet doing at the time, West Coast Swing. I loved it right away, and decided to do what it took to learn it, even though it is considered quite difficult. So, I put in some extra effort, went to weekend workshops in a addition to the regular classes, watched videos, etc.

And now, here's the thing, that wouldn't go on for more than a few months before my wife would start making remarks like "You must be an expert by now, with all those classes you're taking". Or, when I'm signing up for another weekend class next month: "Do you really need to be an expert?".

If I wanted to be an expert and really master something, I should be practicing it for some hours every day. Not some hours every second weekend.

Many well-meaning people will be very interested when a friend or family member starts to learn something new. "You should give us a show!", "When are you going to perform?" two weeks after somebody starts learning to dance or play the violin.

There are surely activities that might be worth watching even when done by beginners. Most are not.

Some people (Malcolm Gladwell) say that you need to practice something for 10,000 hours to master it. That number is completely arbitrary and probably unfounded, but it gives the idea. That's something like 40 hours per week for 5 years. And doing that mindlessly, repeating the same actions over and over, surely wouldn't do it either.

Many people think they're not gifted or not able to learn, because they tried something a couple of times and they didn't succeed. You know, they tried making a drawing and it wasn't good. They obviously have no clue what it would take to succeed. Probably to a certain degree it is the fault of a general anti-mastery atmosphere. Or, we could say, a need for instant gratification. We celebrate people who've mastered fantastic skills, but we usually render the required work completely invisible, leaving the illusion that the mastery somehow was easy or didn't take much time.

Some people show up for the audition in American Idol or So You Think You Can Dance after having practiced for hours per day for years, and they do great. The show makes it look like they do what they do in a few days. Obviously the illusion fools enough people that some people will show up to the same auditions never having practiced anything, thinking they have a chance, and the only chance they get is to look like complete idiots in front of millions of people.

So, if you should be an expert by now, you should obviously have started years ago and have worked on it every day. It takes a lot of practice. And not just repetition of stuff one is trying to do, or that one is repeating in the wrong way. It takes attentive exploration of all aspects of what one is trying to learn. Getting to understand deeply why one has difficulty with some particular part, and how one can overcome it. And then moving on to some other part.

Most people who're really passionate about something, or who are trying to master something, will have a great need to talk about it or think about it. And, there again, unless they're surrounded by people who're passionate about the same thing or learning the same thing, they'll probably find that others have a very limited patience for this. We're used to the TV format. Sure, we'd like to see your audition, and a couple of snapshots of you practicing, and a few soundbites of you talking about your challenges, and then we'd like to see your performance, preferably flawless. But that's of course not really what has been going on. Again, they'd have been working on it for years, every day.

I'm writing in a blog here. Blogs could be a format for talking about what one really is working on, and others might be interested if they're on the same path. But not if they aren't. If you have a somewhat general blog, like this one, and you suddenly get passionate about something specific, and you start writing about that all the time, you would probably lose most of the audience. For example, I was really into aquaponics a couple of years ago. That meant that I spent hours every day doing research, trying to solve problems, or constructing things in the garage or in my greenhouse. I have written about that in other places. I could very well have written several posts here every day, but I didn't, because it would be much too much for most people. Right now I'm passionate about dance, and I could write about that every day. I don't, or I only do it in my private notes.

If you don't already have it, it would be a good idea to seek out a forum where your passion and your learning actually is welcome, also at great length. That's maybe really obvious to some who already have it, but not to others who didn't know where to look. You'd want to communicate with people who're on a similar level of involvement with the subject, or who would like to be. People immediately around you are not likely to follow you, so you might have to go out of the way to find the others. And if what you're into is something really specialized, it is quite possible that you won't find anybody else in the world who's deeply into that. Don't let that stop you. Later on, when you've succeeded, everybody will show up to congratulate you, including those who didn't really have the patience for you working so much on it, or who even tried to talk you out of it.

[ Knowledge / learning | 2014-09-27 00:04 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, September 26, 2014 |  |

|

|

|

At some point, a few years ago, I became good at saying wise stuff very concisely. At some point, a few years ago, I became good at saying wise stuff very concisely.

It was sort of accidental. The challenge I set myself was to say more things that were quotable. It is a Toastmasters principle that one ought to always have some material ready, in case somebody unexpectedly asks you to get up and speak to a crowd. Some stories, some jokes, some unusual facts, some quotes. One could simply collect some of those when one runs into them, put them on a list, and glance at them once in a while so that one is likely to remember them.

And I thought -- quotes -- I can't remember anything I've said that was quotable. Once in a while other people would quote me on something I had written years ago, and I usually was impressed. But I couldn't myself think of anything. So I decided to write it down when I said something that would make a good quote.

Incidentally, Twitter or Facebook are ideal for brief statements. On Twitter you simply can't write more than 140 characters, so if one has any hope of writing something memorable and meaningful, it would have to be within that limit.

I was quickly surprised to find that it was quite easy for me to say something quotable. I had just meant to try to catch it when I said something clever, but by doing that, I started mainly writing things that were clever and quotable. That maybe shouldn't be surprising, one typically gets what one puts one's attention on. Anyway, the result became that I more or less copied everything I said on Twitter or Facebook to my quote list right away. So, now, several years later there are hundreds and hundreds of entries on it.

It is worth noting that even though my initial motivation was somewhat vain and self-serving, to collect clever things I've said in order to sound smart and quotable later, it was something else I managed to tap into.

See, I can't really come up with something clever on command. If I try to deliberately construct a wise and profound statement, I generally can't. I'd sweat over it and just come up with something mediocre and unoriginal. Because it is not really about constructing something clever at all. It is more about discovering something.

The way it works for me is that I'm busy with something else and suddenly, bing, an insight pops into my head, fully formed. That has certainly happened for a long time. What was new now was that words came along with it. I could just write those words down, a sentence or two, and post them on Twitter or whatever. And I would probably pop right back to what I was doing before, having just spent a minute or so noting down or posting that thought.

The cool thing is that most of those little packets of wisdom could be unpacked to something much larger if necessary. If somebody has a question about it, I'd have a lot to say about it, and I'd have examples, etc. Or any of them could be a whole discussion, or a lecture, or a book, if necessary, and if I had time to write it. Or they could just stay brief. What is very useful about the brief form is that it is enough to remind me of exactly what it is about. So, even years later, I could still unpack it into a speech or an explanation. There'd be nothing to forget, because the initial quote says it all, even if it maybe isn't clear to most other people. And it almost always has a built-in integrity and coherence. Nobody ever catches me in having gotten it wrong. I don't particularly mean that to brag. I'm after all only partially responsible. Those thoughts pop into my head from I don't know where. I didn't try to construct them, they don't represent something I painstakingly have figured out. I can explain them after the fact, though.

The downside of saying many little things like that is that I might not get around to the bigger and longer and more detailed explanations and articles. And even though I myself was quite happy with my mini version, and a bunch of people clicked Like on it, I'm quite aware that probably most people didn't quite get what I meant. They might have entirely misunderstood it, or have at least filled a few of their own fixed ideas into it. The advantage of longer form writing, like blog posts, is that the subject matter can be unfolded and illustrated in a variety of different ways, and it is more likely that the reader gets it and that it becomes real and useful to them.

So, I will give myself the challenge of also collecting longer treatments of simple ideas I care about.

[ Knowledge | 2014-09-26 15:15 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, November 6, 2011 |  |

|

|

|

We make many of our decisions based on what we directly perceive. If you have the choice between two cupcakes, and the bigger, more chocolaty one, looks better and the thought of eating it makes you feel better, that's probably the one you'll choose. Unless you directly perceive something else that tells you otherwise, like a little voice that tells you it is fattening, or a hunch that your friend would enjoy it more than you would. We make many of our decisions based on what we directly perceive. If you have the choice between two cupcakes, and the bigger, more chocolaty one, looks better and the thought of eating it makes you feel better, that's probably the one you'll choose. Unless you directly perceive something else that tells you otherwise, like a little voice that tells you it is fattening, or a hunch that your friend would enjoy it more than you would.

We humans in particular also make many of our decisions based on abstractions that we perceive or deduce. A table of calories in your head might make you not eat the cupcake after all. Its price might have a bearing on it. There are numbers and qualities attached to lots of things, which influence your behavior around them. This is symbolic stuff which carries a meaning to us.

Augmented reality glasses isn't yet something that is available to us, but we act as if we're already wearing them. There's an invisible heads up display that superimposes symbolic values and characteristics on most everything we deal with. Abstract information both changes our perceptions of what's right there in front of us, and it gives a lot of extra importance to stuff we don't see at all, which happens elsewhere. It is in our peripheral attention that we need to pay the rent and that there's a meeting in half an hour.

Within this mesh of perceptions and information we make the best decisions we can. Generally speaking, sane human beings will attempt to make the very best decision possible at any time, the decision that maximizes the benefits and minimizes the disadvantages. That has often been called selfishness, but it could just as well be called intelligence. Of course you choose from what is available the best experience with the lowest cost. And if you don't, it is because you have information that assigns value differently. You might be perfectly happy not getting a new fresh fluffy towel every single day in a hotel, because you know that it saves resources to use the same towel several times.

Not everybody makes equally good decisions. Most people try, but some have a harder time than others extrapolating what information means, visualizing consequences. A small percentage of people are altogether unable to empathize with the feelings of others, and will therefore make decisions that only maximize their own individual interests, no matter what costs and pain it incurs on anybody else, no matter whether they're aware of this or not. But for most people, the more the merrier, and they'd happily extend good decisions to those around them, and to the world at large.

So, if, as I claim, most people are benevolent, and they routinely choose the best decision available, why isn't the world a much better place? Most people on the street would be able to tell you what many of the problems in the world are. Pollution, deforestation, resource depletion, war, injustice, inequality, corruption, crime. Yet all of those things are the direct result of our collective actions so far. Why doesn't it add up?

The problem is bad or missing information. We supposedly live in an information age, but unfortunately it is mostly junk information, and the most useful information tends to be missing. If you have faulty information, you'll make faulty decisions. If the information is missing, you'll guess, quite possibly wrongly, based on the faulty information you have. Garbage in, garbage out. If you try to make a decision about the quality of a product solely based on an advertisement, which is meant to mislead you, you are likely to make a mistake.

There are many ways we might help people have better information so they can make better decisions. Creating networks of trust, where you know who's likely to provide reliable information. Independent information repositories about the activities of companies or governments. Raw feeds from the sources of information. Better visualization tools for understanding publicly available information. Training in critical thinking. But the most direct way is to actually count the right things.

A proper accounting system would change the world. If we actually were able to notice the degree to which value is added and taken away from our shared commons, and this information were integrated into our economic system, everything would change very rapidly.

The all pervasive global economic system we're living in uses a unit of measure, money, which is created out of thin air in bank computers and provided in the form of debt to people who're deemed able to pay that debt back with interest. There are a lot of things to say about that system. One is that it is based on the impossible idea of endless growth. Another is that it per definition will introduce a lot of scarcity and lead people to compete with each other for the perceived scarcities. And, important to this discussion, this kind of money only values that which can produce a monetary profit. Almost all resources on the planet, and many metaphysical resources, like ideas, words, thoughts, songs, have been converted into stuff that now is owned and counted in this unit of money. But what's much worse about that is that it isn't at all the valuable things that are being counted. What is being counted is the potential to produce more of those numbers that we count - money. What is being counted is not really most of the things we find valuable. Yes, some of the things that money can be paid for are good and valuable, but many more are terribly destructive.

Clean air, forests, good education, clean drinking water, happiness, creativity, health. If you have money, you can pay for creating more of those things. But that in itself isn't good business, so you would have had to make your money elsewhere first, before you can show such largesse. The very best ways of making money would be in exploiting natural resources for personal profit, leaving the cleanup costs to everybody else, or in speculating in the money system itself, amassing made up numbers, without producing any actual value whatsoever.

It is all in what is counted. All that is needed is to move our money system from being based on self-reflective monetary profit to being based on something more real and valuable. No, not gold, nothing valuable about that, other than it being rare. Our natural environment would be a good choice. Air, land, water, and its productive capacity. Money could be based on our common environment. Thus the real costs of exploiting it or possibly destroying it would necessarily have to be included in the accounting. As would the real costs of regenerating it, so that it can keep being valuable.

The point is that what is being counted, and particularly what is given a value number, will be noticed. If those numbers actually mean that things are more or less easy to get at, we will start changing our behaviors around them. That a styrofoam cup costs 5 cents, and that it doesn't cost anything extra to throw it "away" after using it for 10 seconds and dump it in a landfill, that's a complete fiction. If all the costs were included, and all the benefits weighed against them, the situation would look very different, and most likely you would make different choices.

Individuals don't have to understand the full implications of everything. We're all busy with our particular projects and preferences. It isn't necessarily practical to become an expert on everything and understanding the ins and outs of how a planetary ecosystem best is managed. The economic system should assist us in making decisions that affect the whole.

It is very simple, really. Free market economics can be a perfectly sound self-organizing system. As long as we count the right stuff. I.e. we count the complete costs of stuff, and we try to count as valuable that which we really find valuable. If that styrofoam cup costs $1, and it would cost $2 to dispose of it, and it costs $0.01 cents to reuse your ceramic mug, you naturally will make a different decision than before. It doesn't take any persuasion, it doesn't take any idealistic desire to do something for the planet. Even if you're acting completely selfishly, the cheaper choice is likely to seem the better one. Unless there really were a unique value in drinking once from a styrofoam cup which somehow made it worth the trouble to make some extra money so you can buy it.

It doesn't have to be called money. We're basically talking about information. When the supermarket writes "Organic" on a sign next to the gnarly little lemons that cost a bit more than the good looking ones, it allows me to make an economic decision. I might be happy to pay a bit more to know that the coffee is "fair trade". But numbers would be better. We all know that $4 is better than $5 when we need to pay it. We aren't all so thoughtful as to consider more abstract implications than that. So, it would be better if the money system itself were based on something real.

If we can simply see the world a bit better, we make better decisions. That seeing includes the numbers attached to things. The numbers we need to pay is an important aspect, but there can be others. Even if nothing changed about how things are priced in today's world, if I had a heads up display that told me the actual costs and actual benefits of a given item, I'd act differently. So would most people. Buy this item for $4 and a kid in Sudan will no longer have clean drinking water, or buy this one for $6, which is produced in a sustainable way. Yes, it needs to be less crude and more sophisticated than that. And it can be. We can be pretty good with numbers. We just need to apply them to the stuff we actually want to measure.

It is a simple game we humans like to play. Give us a number and convince us it is good, and we'll put our creativity and hard work to use in making that number bigger. We're pretty good at it, but it is also our weakness. Unscrupulous people might temporarily trick us into maximizing their numbers instead of our own or instead of our overall shared numbers. We've caught on to that now. Still, we like making numbers bigger, so let's at least start doing that with some numbers that count what counts in the world.

[ Knowledge | 2011-11-06 21:33 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, January 23, 2011 |  |

|

|

|

It's when you act and speak in harmony with who you really are, what you feel, and what really is going on. It's the truth. Unfortunately we tend to be afraid of it. It's when you act and speak in harmony with who you really are, what you feel, and what really is going on. It's the truth. Unfortunately we tend to be afraid of it.

Our society seems organized so as to thwart authenticity at every turn. There are rules to follow. You need to live up to expectations. You need to be able to back up your words and your actions with reasons and logic and references to more important words uttered by established authorities. You'll often be rewarded for constructing convincing lies, apparently out of facts. But not often for expressing the truth.

Imagine that it all changed. Most people most of the time doing and saying what they actually feel is right for them, as opposed to what they're supposed to do or say.

It could just somehow become fashionable one day, for unknown reasons. An evolutionary shift. Or, a movement could be engineered. It would require some prominent role models. Some famous people who stand up and say the truth, despite the consequences. Collections of success stories, people who did the right thing and it turned out well.

Just even talking about authenticity is difficult. Our language makes it sound a lot more fuzzy than it is. We can express our authentic experience in words, but the problem with statements made of words is that they end up kind of frozen. Words are transportable, tempting us to take them with us and apply them to other contexts. Where they possibly might no longer fit. Yet we try to hold each other to the standard of standing by our words, or being able to back up our words with strings of arguments.

I'm implying, mind you, that there's a depth of unseen wisdom inherent in authenticity. Or, at least, that's the aspect I'm speaking to. There are lots of things you can say that literally are true, but which don't get you anywhere good. Lots of things that you can feel at any given point that maybe aren't really YOU. And one could have long discussions about which things are authentic and which are not. What I am talking about is that inside of you there's a compass. There's a sense of whether you're aligned, not just with yourself, but with the universe. With the environment, with others, with life. At multiple levels. It's not a separate thing, it is a connected thing. And the claim is that it is a lot smarter than most of the complicated but simplistic structures we've set up to manage our society.

We're used to thinking of it as something vulnerable. It can sometimes be awkward and embarrassing to just say the truth. You might sound naive, you might open yourself up to all sorts of attacks. But, really, what I'm talking about is quite the other way around. You might plug into the collected wisdom of the universe, or at the very least, the vast parallel processing capability of your sub-conscious mind. As opposed to the card house built of societal norms, the expectations of others, and your collection of acquired factoids and supposed-tos. What really IS is usually a lot deeper than what "should" be. We might get used to it also being more viable, stronger, more productive.

[ Knowledge | 2011-01-23 13:46 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, August 23, 2010 |  |

|

|

|

This is an answer to the question How does one perform a "cortico-thalamic pause"? on Quora. This is an answer to the question How does one perform a "cortico-thalamic pause"? on Quora.

The idea of a "cortico-thalamic pause" springs from General Semantics and was popularized in the Null-A science fiction books by A.E. von Vogt.

It has also been called a Semantic Pause or a Cognitive Pause.

Thalamus/Thalamic is here used as a shorthand for the lower brain functions, associated with feelings, sensing, pain, pleasure, instincts, bodily functions, etc. Massive sub-conscious parallel processing goes on there and responses are often immediate.

Neo-Cortex/Cortical is the shorthand for the higher, more recently developed, brain functions, associated with conscious thinking, reasoning, language use, deliberate decision making, etc. It can do abstract thinking, but can't focus on more than a couple of things at the same time.

We easily get in trouble when we mix the two. Our ability to abstract is rather new and apparently a bit faulty. The cortex might construct a "meaning" for some lower level sensations which gives rise to faulty decisions. The thalamic system might launch instant action based on what was sketchy reasoning in the cortex. E.g. killing somebody because they have the wrong religious belief.

Note that I don't personally buy the idea that consciousness originates in the brain. But clearly it is involved in the process, and what we know about brains is very useful in helping us understand the structure of thinking.

The idea of the semantic pause is basically to be conscious of the link between one's reactions and one's reasoning, and to make sure they're in sync. It doesn't have to be a literal pause in time, but it could be. It is an equivalent of "count to ten before you...".

If you were about to take impulsive physical action, the pause would allow you to think through the logic and implications of what you were about to do.

The other way around, if you thought you just arrived at a logical, well reasoned conclusion, a semantic pause would allow you to notice what you actually feel about it, what your instincts tell you. Does it feel right? Does it work?

The pause is an opportunity for testing all levels of the machinery that is in play. If you were doing an experiment that you were about to draw certain conclusions from, it would of course be very wise to check and double check everything from the bottom up. What are the characteristics and limitations of the parts and materials you're using? Are there outside influences? At which points do you abstract (simplify) a complex phenomenon into something more simplistic? Are there ambiguities? Are there multiple possible interpretations? What would the words you use mean to different people?

The objective is to take decisions and actions that are coherent, congruent and sane at all levels. The cortico-thalamic pause is a system check and a consistency check at and between multiple levels.

The primary ingredient is consciousness. Pay attention. Be aware. Examine everything that is there, including your own thoughts, your premises, your feelings, what you perceive.

There are certain tools that are helpful. A consciousness of abstraction is vital. Simply being aware that there are many levels of abstraction between what really is there and what you put into words and thoughts. Not just being aware of that, but specifically examining the transition between a "thing" and its abstraction. At what point do some rays of light become a picture in your brain? At what point do you group it together with other tables you've seen, to identify it as a "table"? At what point does the word "table" lose its connection with the particular image you saw?

There are many ways that perceptions and cognition can be fooled. There are fallacies, there are the mis-directions of stage magicians. You'd need to be well versed in such tricks, and you'd need to be skeptical about what you're being presented with. Is there any way you might be fooled? It might not really be a table, just because it looked like one, or because somebody says it is.

There are degrees to all of this. For a person to be expected to act and respond sanely, he/she must have a certain command of infinity valued logic. Which means to always be aware that there are degrees of abstraction, degrees of certainty, etc., and to be able to make the best possible conclusions based on that, despite the always present degrees of uncertainty. Somebody who thinks in black and white two-valued logic is easily manipulated and fooled.

If you have some of these skills, they will naturally be active in parallel. It will be something you'll be aware of more or less all the time.

On top of that, it will be a moment of reflection, paying full attention at as many levels as possible.

Imagine yourself waking up at a level of a dream, like in the movie Inception. How do you know if you're dreaming? Can you trust your perceptions? Are you being fooled? Is there any test you can do to verify your conclusions?

It is that kind of awareness, but applied also to possibly very routine moments in life. Pay attention. Question everything. Perceive. Feel. Think systemically.

[ Knowledge | 2010-08-23 01:31 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, June 27, 2010 |  |

|

|

|

By Oglaf. Yeah, it's a bit subtle that doubt thing.

[ Knowledge | 2010-06-27 02:28 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, October 25, 2009 |  |

|

|

|

It is a good thing that many people have keen perceptions of the material world around us. I mean, that you can experience something and be pretty sure what you experienced and that it really is there. It allows for developing mental models that are calibrated with the material world, e.g. science, and thus to get very consistent results to certain very consistent actions. You'd probably want a surgeon to have very keen perceptions. It is a good thing that many people have keen perceptions of the material world around us. I mean, that you can experience something and be pretty sure what you experienced and that it really is there. It allows for developing mental models that are calibrated with the material world, e.g. science, and thus to get very consistent results to certain very consistent actions. You'd probably want a surgeon to have very keen perceptions.

But many otherwise pleasant people are not good at distinguishing between perceptions and opinions. I.e. they don't quite know the difference between knowing something because you've observed it and verified it, or because you hallucinated it. An opinion based on an emotional reaction is a lousy source of knowledge compared to perception or measurement. Folks who use guessing as their method of knowing stuff or making decisions can probably be perfectly adequate in many professions, but not in the ones where it is important to get things right, such as engineers or pilots.

Then again, keen perceptions and an absence of hallucination is not quite enough. You wouldn't want to be a passenger in a car driven by somebody who only goes by what they see and hear. You certainly shouldn't let such a person ride a motorcycle, as they'd probably not survive more than a few weeks. What would be missing would be the kind of intuition one has when one has mastered a skill. Where you somehow predict that a car is about to turn in front of you, despite that there's nothing visually that gives it away. Where sub-conscious or extra-sensory cues tell you something useful, despite you not knowing exactly how.

I suppose I'm thinking about this because I'm trying to convert parts of my life from being based on emotions, opinions and hallucinations to being based on something more real. Oh, I have very sharp perceptions in some areas, and super-human intuition in others, but in fields like finance, business, marketing, or even in "work" in general, I have more difficulty than I ought to have. Blindly making dumb decisions and failing to learn what works, even when frequently exposed to success.

A good start is to be able to recognize when there's something one doesn't know, and to then go and learn it.

[ Knowledge | 2009-10-25 17:04 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, October 15, 2009 |  |

|

|

|

It is such a fundamental thing that we do, and still most of us are hardly aware of it. We abstract the real world into each our separate set of abstractions, and then we get pissed off with each other when our abstractions turn out different. It is such a fundamental thing that we do, and still most of us are hardly aware of it. We abstract the real world into each our separate set of abstractions, and then we get pissed off with each other when our abstractions turn out different.

I'm using the word abstract as a verb here. Defined as "to summarize or epitomize". I.e. you simplify something into a much smaller and maybe more portable version. We'll often further abstract the abstraction, any number of levels deep.

If I walk around with some kind of image in my mind of what a table is, it is because I have created an abstraction of the real thing. That's called learning. Even for such a simple thing it is a relatively complex abstraction, allowing me to recognize tables, even when they have many different sizes and colors and shapes and number of legs. Being able to recognize most all tables is very handy, much easier than to just perceive some kind of fog of trillions of sub-atomic particles.

I also abstract my mental model of tables further by accepting that such a thing is called "table". Which is just as handy, because now I can talk about it, and send some statement about tables over even great distances, and somebody else can receive my communication and expand it into the understanding that I'd like a place to sit at their restaurant. As long as we're talking about physical objects, this usually works out with minimal problems.

But when we do the same thing, repeatedly, with more fuzzy and complex problems, we become more and more likely to get into trouble. I might form complex ideas about "relationships", "work", "right and wrong" or "freedom", and they might be very far removed from any actual experience. Opinions about abstractions of ideas one heard described by somebody else who had abstracted them from interpreted abstractions of abstractions of experiences that somebody once had.

The horrifying thing is that many of us go around being very sure about the absolute truth in our abstractions. You know, being very, very sure that our point of view or our religious belief or our scientific theory is fact. That's of course raving lunacy, but since the majority of us are doing it, it isn't worth the trouble to try to lock such people away in insane asylums. So, we just fight about it, have wars and elections about it, and try any which way we can to coerce others into accepting our abstractions, because they're the right ones.

The way out, towards more sanity, is to become conscious of abstraction. I.e. become aware of how and when you're abstracting, and how much, and based on what. And becoming able to go in the other direction, if necessary.

It goes kind of like this, through various levels:

- There's something fundamentally there. The quantum soup. Reality with a capital R. All-that-is. The Multiverse. God. Something way, way beyond anything we can talk about or theorize about.

- Nevertheless, something happens within that indescribable something.

- It leaves traces - light, sound, smell, radiation etc

- It is perceived through a nervous system - seeing, hearing

- It is interpreted into a picture, a sound, etc

- We make interpolations, extrapolations, guesses, to fill in the blanks

- We invent or select words that describe our experience

- We have a semantic or emotional reaction to what we think happened

- We make mental models of how things work and what to expect

- We communicate with language, exchanging ideas about ideas

- We construct bodies of knowledge, beliefs, systems, e.g. science

There are many more layers of levels to this, but you get the idea. All of this is useful, of course, allowing us to operate at a "higher level". But when we mistakenly start assuming that an abstraction is better than that which it was abstracted from, we start going insane. The anti-dote is to always remain conscious of abstractions.

Further reading: Wikipedia: Abstraction, Consciousness of Abstraction, Wikipedia: General Semantics.

[ Knowledge | 2009-10-15 08:32 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, June 29, 2008 |  |

|

|

|

In everyday usage, we often use "complicated" and "complex" interchangably. Which makes it a little bit hard to discuss complexity. I mean, the "good" kind of complexity that you find in nature, for example. In everyday usage, we often use "complicated" and "complex" interchangably. Which makes it a little bit hard to discuss complexity. I mean, the "good" kind of complexity that you find in nature, for example.

We could say that we need the scientific definition of complexity, but science has unfortunately come up with at least 32 different definitions, that don't agree with each other. But if we cut through the confusion a bit, something like this would be workable:

Complicated is when something contains many intricately combined parts. It is something that is hard to figure out. Even if you do figure it out, there's no guarantee that things are put together in a sensible way.

Complex is when something acts as a system, and it is exhibiting systemic properties that aren't obvious. It is something more and different than simply a sum of its parts. There might or might not be many parts, but the result is something not very transparent, which takes on a life of its own in some fashion.

An Airbus A380 is complicated. A jellyfish is complex. The Paris Metro network is complicated. How people use it is complex. Your skeleton is complicated. You are complex. A building is complicated. A city is complex.

One scientific view, which tries to cut through the multitude of definitions of complexity is here. It says basically that complexity is any real world system who's properties can't be explained by being reduced to any one formalism. Formalisms would be stuff like laws of mechanics (vectors, forces), or pretty much any "Newtonian" kinds of laws.

Life is complex. Life forms, eco-systems, the behavior of indivual animals or humans, or groups of them, all of that is stuff that is beyond old-fashioned reductionist science. You can dissect them and catalogue what they're made of, but it tells you little about what makes them do what they do. Consciousness is complex. The tendency of nature to self-organize is complex. The universe is complex.

Many complicated things can be understood by isolating them from everything else, by taking them apart, understanding all the parts, understanding how they're put together, and we might then know something useful that we can apply the same way again and again. We can invent complicated things the same way, by putting together parts we understand, based on principles we understand. That all works quite well for mechanical stuff, and has brought us bridges and automobiles and phone systems and western medicine. Some people are so happy with all of these that they intuitively have adopted the belief system that this really is all that exists: the stuff we can take apart and put back together again.

But the much bigger part of existence is all the stuff that's complex. Life itself is something mysterious and very complex. The fact that we exist at all is quite a mindblower. The fact that the universe exists and that it appears to be somehow ordered and livable, that's quite wild. Consciousness is something strange and hard to fathom. All of that is complex. Stuff that is complex tends to defeat attempts of isolating it and cutting it to pieces. It seems to often relate to other stuff that is outside the part you've chosen to analyze. It is like you can't address complexity without being open to dealing with the whole universe.

All of that makes complexity fascinating to look into, but it requires different models. Where you can reduce complicated stuff into pieces that you can study and understand separately, complexity seems to require the opposite. You need to chunk it up and find what principles appear to be at work. Inductive reasoning, rather than deductive reasoning.

[ Knowledge | 2008-06-29 16:47 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, February 20, 2008 |  |

|

|

|

Fun article by Linda Moulton Howe: "Could Our Universe Be A Virtual Reality Processed By Other Intelligence?" about a professor in Auckland who wrote a paper about that. That's not a new discussion, but it is always stimulating. In part because it makes us question a number of things about our existence. Which is a bit dangerous, of course. Quote by John Vacca from "The World’s 20 Greatest Unsolved Problems": Fun article by Linda Moulton Howe: "Could Our Universe Be A Virtual Reality Processed By Other Intelligence?" about a professor in Auckland who wrote a paper about that. That's not a new discussion, but it is always stimulating. In part because it makes us question a number of things about our existence. Which is a bit dangerous, of course. Quote by John Vacca from "The World’s 20 Greatest Unsolved Problems":“Quantum physicists who work with quantum theory every day don’t really know quite what to make of it. They fill blackboards with quantum calculations and acknowledge that it is probably the most powerful, accurate and predictive scientific theory ever developed, but the very suggestion that it might be literally true as a description of Nature is still greeted with cynicism, incomprehension and even anger.” Theoretical scientists can propose outrageous theories about how the universe works, but you easily get in a bit of trouble if you propose that it might have something to do with our everyday existence.

Anyway, Professor Whitworth there has worked for years on finding analogies in the computer world for how the world works, and he also has some interesting answers for how certain qualities of the physics we discover seem to back up the idea that the universe is a simulation. Whis is the subject of the interview in the article.

So, how would, for example, the limited speed of light indicate that the universe is a simulation?There is a fixed amount of processing available, let’s say, in space. So, if an object is being passed from point to point in space, there’s only a certain amount of processing available to each point in space, OK? And if that processing is involved in the calculation of movement, that changes the processing. The smaller and smaller amount that is left makes the mass seem greater and greater. Or, expressed in a computer screen refresh metaphor: Your screen has a certain rate with which it refreshes, which depends upon the little points that make up the screen. And each of these points can only flash on and off at a certain rate. So when a pixel moves across the screen, what it means is that it starts off and one point flashes. Then that point turns off and the next point flashes and so on. So, the rate of movement depends on the rate of flashing of the screen. It’s the refresh rate and it might be 70 megahertz; it might be 80 megahertz ... But whatever it is, it doesn’t matter. That’s going to mean that a dot can move across your screen so fast and no faster. So, the speed of light is just the screen refresh rate, that is fun. What about the Big Bang? The Big Bang is when the simulation was started, when the virtual processing began...

A lot of people have trouble with the idea that Time began at the Big Bang. I know I certainly did – and that space began. How can Time begin? Surely something must have caused Time to begin, but how can you cause anything if there is no Time to have a prior event?

But if you say we’re in a virtual reality, or local reality, then the Big Bang is when our Time began and our Space began. That is perfectly reasonable. So, if you go online to Second Life or something, when you switch on your computer and enter the reality. That’s when that Time - or perhaps when Second Life was created – that’s when its Time began. And here's an angle I like: Now, if the physical world is a virtual reality that does not necessarily imply that our consciousness is in the virtual reality. It could be exactly the same as your playing an avatar in a game. It’s conceivable that while everything you see and hear is definitely part of the pixels – or certainly, part of the virtual reality – it’s possible that you are not looking from inside the virtual reality.

This relates to very deep questions about whether a mechanical universe could create consciousness. I must admit I haven’t worked through all these things yet, but it’s certainly something that has concerned a lot of people from Descartes on. Actually, if we imagine that the universe is a simulation, it makes it all the more unlikely that the consciousness which is you is fully generated by the simulation. There'd be no point to Second Life it you couldn't, from the outside, step into it and experience the simulation. You can change your hairstyle, or your body style, and you can redecorate your house, but if there's nobody there, there's just no point. Same thing with a universe. The postulate is that the physical universe – if indeed it is a virtual reality – cannot create itself out of itself. It’s just not possible. So, there must be Something outside of it. Therefore, quantum mechanics is describing that Something. The equations of quantum mechanics, which are quite different from our concepts of physical reality, are describing this Something. The idea is that what we are seeing as we walk around is just an interface which is calculated at the moment when we look, sort of an on-demand thing. Now we're talking.

Of course, even if we conclude that the universe is a virtual reality, it doesn't necessarily mean it is running inside some huge computer. It means there's processing going on, but what medium it exists in, that's another matter.

[ Knowledge | 2008-02-20 16:39 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, December 8, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

An article I had meant to comment on for some time: "Playing Go - Braille Alphabet - Cognition - Creativity - Intelligence / Choice" by Heiner Benking. I don't always understand everything Heiner says, but we're on the same wavelength. An article I had meant to comment on for some time: "Playing Go - Braille Alphabet - Cognition - Creativity - Intelligence / Choice" by Heiner Benking. I don't always understand everything Heiner says, but we're on the same wavelength.

In today's information world I feel rather blind. There is more information available than ever before, and it is more easily and more instantly accessible. But it is hard to make sense of it, other than in little pieces at a time. I feel like a bat without my sonar, flapping around in the dark, bumping into stuff.

To make sense out of what is going on, you don't just need a lot of data. You don't just need a zillion disjointed pieces of information. It helps a slight bit that I can search on information by keywords, or that I can get chronological lists, but not much.

For information to have meaning, it needs context. You need to know what it relates to, and how. You need the background, you need to know how it came about, and you need to be able to cross-relate it with other information.

We do have new ways of discovering context and supporting information in the internet world. I can more easily than before find out more about an author of some piece of text. I can more easily get to talk with them. I'm more likely than before to already know them, and have some idea of their history. But the information we're talking about is still isolated clumps of somewhat arbitrary data. Articles, blog postings, comments, e-mails. People can organize them, bookmark them, tag them, link to them, quote them, but they still fit together rather badly.

A fundamental problem is in how our language works. It consists of words strung together. That is adequate for telling stories, or for working out how to work together on common ventures, or for sharing our day to day experiences with each other. Even for discussing deep philosophical issues. But it is not very adequate for examining, understanding or sharing something that is really complex. It can be done, but it is really cumbersome.

Yes, 10s of thousands of people might work together to design and build an A380 airplane, despite that none of them could do it alone. That takes 100s of thousands of documents and diagrams and complicated communication system. And they still discover when they try to put it together that the pieces the Germans made don't at all fit into the pieces that the French made. Nobody could see it, even though it was obvious once you saw it. Because large amounts of information don't necessarily add up to seeing the whole.

And it is seeing the whole thing we have a dire need for. The rapidly more complicated and complex inter-connected globalized world. Hardly anybody can see what really is going on, so we each specialize in some little slice, which we can gather enough information about to be able to seemingly talk intelligently about.

The computerized information revolution is mostly amplifying the little part of our minds that we could call the analytical or logical mind. Left brain. You know, where we try to focus on some facts in order to deduce their logical consequences. The same part of our mind that is incapable of focusing on more than 5-7 different things at the same time.

But we're not getting much help for the bigger part of our minds, the sub-conscious, the intuitive, the wholistic, the right brain. Which probably is atrophying rapidly.

Oh, the internet world has lots of raw material one could be creative and intuitive with. But it is not particularly wired to amplify our wholistic, intuitive way of seeing things.

I get back to dimensions again. The space of information we now live in has a great many dimensions to it, many more dimensions than we've lived in before, many more degrees of freedom. Yet all our tools have only a very small number of dimensions to them, and many limits and restrictions. You move around on the net and read documents, you can get lists of them, organize them on your desktop. You use an assortment of different applications that all have their own features, limitations and peculiarities. Much of that is cool. But all of it either has too few dimensions or not access to the data I'd want to see.

I'd want to not just have access to 100 billion articles, but more direct access to the actual information sources. Visual, auditory, kinesthetic channels, digital channels, all the raw numbers. And I'd want to be able to organize and visualize that as it suits me. Again, not as a catalog of articles, but as a mostly visual information space with many dimensions. And, since I can't make sense of it all alone, I need ways of navigating in multi-dimensional information spaces shared with others, and model shared meaning within them.

I'd certainly need the semantic web along the way there, or something better. A universal way of storing information so that it can be cross-related with any other information at will.

As to how to look at it, I don't know how exactly that will look, but I do know it has to be several quantum leap paradigm shift orders of magnitude above the collaborative newspaper interface we have to the net today.

It can happen in many small steps, of course. Google Earth and iPhone multi-touch interfaces go in that direction. Simple intuitive ways of accessing vast amounts of information quickly, without it ever getting complicated. More clever inventions like that might take us somewhere.

Anyway, back to Heiner's article a bit. He references some concepts and terms that hint at some of the thinking needed. And envisioned solutions like: COGNITIVE PANORAMA

A conceptual superstructure that defines and identifies topics as logical places, displays relations and connections within these topics or issues"

This concept has been introduced by H. BENKING. The following comments are BENKING's explanations, plucked from a series of papers and lectures (see bibliography)

"The cognitive panorama is a metaparadigm to counteract cyberculture's anticipated impact due to its: 1)open-ended universality, 2) loss of meaning' 3) loss of context"

It is now obvious that we risk drowning in an ocean of incoherent data which could lead us to total conceptual anarchy.

According to Benking, the proposed cognitive panorama "allows us to embody and map concepts in their context and develop common frames of reference"

Such a conceptual superstructure " helps us to locate and become aware of: 1) what we know or miss, 2) where we are and what we think, 3) where we miss, underuse or manipulate information. By avoiding a "flat" chaotic mess of data which leads to the known "lost-in space" syndrome, we actually define cognitive spaces.

Through reflection on conceptual positions, outlining and embodying situations or topics (logical places or containers) we can follow meaning into embodied context and semantic spaces, and also scrutinize abstract "realities" by exploring participatory and collaboratory approaches.

®Conceptual navigation; Convertilibilty of meanings; Ecocube; Harmonization; Knowledge map; Underconceptualization Yeah, I'd like one of those.

I think humanity has the potential for a great evolutionary leap, or several. But just like software lags years behind the capabilities of hardware, our information structures lag years behind the actual information. I hope we somehow can catch up, so I can feel a little less blind.

[ Knowledge | 2007-12-08 23:53 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, August 19, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

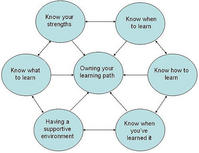

This is the chart that Ton Zilstra and Elmine Wijni put up for their converstion on Owning your learning path at the last Reboot conference. I don't know if we particularly arrived at any conclusion, but learning is an important subject, and maybe we made some kind of progress. How can one own one's own learning path, i.e. take responsibility for arranging things so that you really learn what you want to learn, and you know what you learn, etc. This is the chart that Ton Zilstra and Elmine Wijni put up for their converstion on Owning your learning path at the last Reboot conference. I don't know if we particularly arrived at any conclusion, but learning is an important subject, and maybe we made some kind of progress. How can one own one's own learning path, i.e. take responsibility for arranging things so that you really learn what you want to learn, and you know what you learn, etc.

One inroad to any subject is of course to break it down a bit into components. Like, from that chart, for learning:- Knowing what to learn

- Knowing when to learn

- Knowing how to learn

- Knowing when you've learned it

- Having a supportive environment

- Knowing your strengths

I'm sure it would be useful too to know what learning really is. But all of it seems to be about having a consciousness of learning. Rather than hoping to randomly learn something once in a while, or leaving it to somebody else to teach you, you could possibly be aware of the pieces yourself. You could decide what you want to learn, and you could arrange things so that it is more likely that you will, and you can recognize the opportunities when they're there.

Actually it gets me to think about a more general subject: how to create tools to support any of a number of purposeful activities. You know, if there's something you want to do, there are of course tools that help you organize your progress towards doing it. I'm thinking of personal or group organization tools, like in a program or web page. And I'm very interested in the general subject of patterns, and of how to arrange things so that certain things are likely to happen.

For example, just by creating a few bins for certain named bits of information, you're creating an organizational structure that makes certain things more likely to happen. If you simply made a web application that had 6 boxes, where you could write answers to What To Learn, When To Learn... etc, you'd already have something. That would force you to pay attention to these things and come up with answers you maybe otherwise wouldn't think of.

But I'm also thinking of a type of software that doesn't really seem to exist. One that guides you through an activity in a way that corresponds with what you're trying to do. For example, if you were doing a brain storming session, you'd need some tools that inspired you to come up with new ideas, so maybe various kinds of random input that stimulates lateral thinking. And you'd need some bins in which you can place whatever you come up with, and maybe some other bins for picking out the most promising ideas

Or, if you were having a meeting with a particular goal, the organizational system would be different. There it wouldn't just be about coming up with ideas, but about ending up with a solution, or an agreement. So, you need different tools to help you do that, that show you how much progress you've made towards the goal, and what's still missing.

Different tools are calling forth different patterns. A blog or a wiki or a chat room each make you do different things. Like, a blog, even if it is collaborative, doesn't help you to arrive at common decisions. Rather, it helps you post anything you feel like, taking the conversation in different directions, but probably not towards a point of convergence. Because a blog is not a convergence tool.

There's a bit of a scarcity of tools that help people converge and make decisions together and accomplish goals. There's project management software, of course, but they don't necessarily help you much in developing the plan in the first place.

Learning is one of those things that both are directed (convergent) and scattered (divergent). You might know what you want to learn, but you probably don't know exactly where and how, and you might have to study a variety of things before you know better. So, you need a variety of tools. You need ways of exploring all sorts of subjects and remembering what you found. And you need ways of keeping track of your progress towards your stated goals, so that you can know when you get closer, and when you've made it.

What am I trying to learn right now? I can't even answer that readily. I'm trying to understand universal patterns, but there's a lot more. And how can one do something effectively if one doesn't know what it is, how to do it, and when, and when you've done it?

[ Knowledge | 2007-08-19 19:29 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, August 16, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

A post from Dave Pollard a while back. It is short, so I'll just quote the whole thing: A post from Dave Pollard a while back. It is short, so I'll just quote the whole thing: Nobel chemist and pioneer complexity expert Ilya Prigogine is cited by my friend Andrew Campbell as saying that nature has no secrets -- everything we want or need to know in the world is waiting to be discovered. That means it is waiting for us to be ready to learn it, which presupposes that we have: - Capacity to understand: That's not just a function of brain capacity, but also the ability to pay attention and to be open to new ideas and possibilities, and to imagine;

- Need to understand: Either an urgent adaptive/survival need, or intellectual curiosity to discover; and

- Tools to understand: The toolkit with which we were endowed by nature is comparatively poor (consider our relatively feeble eyesight, dim sense of smell, slow speed and inability to fly), but we have compensated for it with our ingenuity, especially at biomimicry -- inventing new tools that mimic the best nature provides.

We have a need to understand -- the challenges we face as a society have never been greater. And although our man-made tools are fragile and clumsy by nature's standards, they give us what we need.

What we are lacking, I think, is capacity. Despite (or perhaps because of) our large brains we are inattentive, prone to erroneous prejudgement, distrustful of our intuitions and our subconscious knowledge, and we suffer from dreadful and growing imaginative poverty. We are seemingly unable to grasp complex issues and concepts well -- we are so left-brain heavy that we over-analyze and over-simplify, and we are driven (I suspect because of our increasingly poor learning habits) to create mechanistic, complicated explanations for organic, complex phenomena. Then, when these explanations fail, we add further levels of complication, until we have thirteen-dimensional universes with vibrating strings.

We try to deduce when we should induce. We analyze when we should be synthesizing. We look for root causes when we should be looking for patterns. We try to impose order when we should let it emerge and study why it emerged as it did. We try to change and control our environments when we should change ourselves to adapt to them.

So what we should do now is build our capacity to understand -- capacity of attentiveness, openness, imagination, intuition, subconscious awareness, appreciation of complexity, ability to learn and intuit and induce and synthesize and see patterns and adapt and let come and let go. And then show others in our communities why this capacity is so important and help engender it in them, too.

Then we will be ready, together, to discover what nature has been waiting to show us and tell us. No grand unifying theory of everything -- just an understanding of how the world really works, and why our current way of living is unsustainable, unhealthy and unnatural. And what to do to make it better. Very well said, Dave. Can't say it better, so I'll just say what it brings up for me.

Humans have an amazing opportunity, but maybe only within a brief window of time. We can think abstractly, so we can communicate, work together and develop technology. But we're also bad at thinking abstractly, and we fail to include our own shortcomings in the equation.

We have fantastic minds, but we don't have any organized body of knowledge about how they work and what we can do with them. To some degree in various self-help disciplines, but nothing that's integrated into the main things we do together. Science comes with no complementary understanding of the human mind, which is a major oversight, because science is mostly a mental activity. Groups of people perceive stuff and try to construct mental models that allow them to predict what they'll perceive in the future. That's somewhat of a ship without rudder if you don't at the same time have a concept of how you perceive, how you abstract the work into mental models, and how beliefs work.

How do we learn, how do we think, what's the sub-conscious, where does intuition come from? These ought to be very central subjects, but you don't see much more than scattered studies done on one isolated piece of the puzzle or another, which makes for interesting popular science stories about various kinds of experiments and studies. But it is somewhat overlooked that WE ourselves, and our minds are an integral and central component in what we make of the world.

I thought general semantics maybe could have caught on. It isn't everything, but it is at least a valiant attempt of including our mental processes in the practice of science, or politics, or anything else important we do as a society. It is rather dangerous to hand the controls of anything important to a human being who isn't aware that their thoughts are just over-simplified abstractions of reality. People who think that their two-dimensional cartoon mental pictures ARE reality have no business leading countries or operating heavy machinery.

And how do we learn? That ought to be a very central question, because that's largely what we do in life, and what's what we do together. We try to figure out the best ways of doing things, and how to maximize the good things we can do while we're here. Don't we? And yet learning is mostly about occupying kids for 12 or 17 years, having them read a lot of books, and hoping they somehow get something out of that. All due respect to the teachers of the world, but it would make sense if somebody actually put together and applied the very best ways we can find of actually learning.

We ought to be feeling the need already, yes. There are lots of things that aren't working well. We ought to be motivated to do better.

Do we have the tools and the capacity? Not well enough. I suppose we can say that the tools would be the external levers of learning, and capacity would be the internal. We both need to organize some things in the outside world so as to facilitate learning. And we need to organize our internal world so as to actually be learning. As to both, we're somewhat in the stone age. We learn stuff, but very haphazardly.

The challenge is how to effectively deal with complexity, when we mostly are using a part of our mind that is lousy at doing so.

It's the old story of a human being able to pay attention to just 5-7 things at the same time. You might understand a model of a problem or situation if it has 2-3 dimensions to it, but not more. If presented with anything that has more dimensions or variables, you'd tend to default to some favorite cartoon belief that simplifies things into just a few variables. We make as if we're dealing with big, important, complex scenarios, but we do it with those minds that can only think a handful of things at a time. There's a big disconnect.

I think we're actually a lot better wired than we readily think. Your sub-conscious mind deals with millions of variables quite well. Your intuition does great with complexity. You probably do have the equipment you need to operate at a much higher level. But it isn't necessarily going to work if you leave your 5-7 bit mind in charge.

Paying attention, being open, imagining, yes, I'm sure that's part of the puzzle. But those are things you can't put in a test tube and measure, so we have to make some kind of quantum leap over the need to do so. We need to learn how to perceive, how to learn, how to know, how to be conscious of what we know and what we don't know.

[ Knowledge | 2007-08-16 21:57 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, August 15, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

NY Times article about researcher/philosopher Nick Bostrom, who has concluded that there's a high mathematical probablity that we're all living inside a computer simulation, created by technologically advanced descendents of ours in the future. Although his gut feeling tells him that it is only 20% likely that we actually are living inside a simulation. NY Times article about researcher/philosopher Nick Bostrom, who has concluded that there's a high mathematical probablity that we're all living inside a computer simulation, created by technologically advanced descendents of ours in the future. Although his gut feeling tells him that it is only 20% likely that we actually are living inside a simulation.

I always find that kind of conversation stimulating. We very well might live within The Matrix. It might be a computer simulation. Or this might be a universe created by some advanced race from a previous universe. Or the quantum soup universe might just basically work as if it is a simulation, where the reality we experience is the result of our laser beam of consciousness hitting the neutral stemcell type of quantum particiles, which happily will be whatever you want them to be.

But there are things that bother me. Huge fallacies that tend to appear in such a discussion.

There's the very widespread AI superstition that if you make a computer program that is sufficiently complex, it will be conscious and have its own thoughts and feelings. And that this simply is what consciousness is. So that if we make a simulation of your brain, it will think that it is you. That's a load of hogwash, in my opinion, and nobody has succeeded in demonstrating anything remotely like that. The corrolary of the idea is that if you're a sufficiently good simulation, you wouldn't know. Which is a very upside down way of looking at things, and if you believe it, you ought to be worried as well about your soul being stolen when somebody takes a picture of you.

And then there's the God thing. People who have this kind of discussion, of intelligent simulations in artificial realities, are usually atheists, and will usually take time out of their schedule to explain to you why you're a complete moron if you think the universe somehow is intelligently designed, or there possibly could be any intelligence guiding its evolution. And in the next breath we're having a discussion about exactly the same thing, the possibility of you just existing as a simulation in the computer of some advanced alien, who might or might not be benevolent, who might turn you off when he feels like it, if he doesn't like what you do. Uhm, sounds a lot like that God in the sky with the grey beard. So do you believe in it or not?

I don't. But I do believe in the primordial existence of consciousness, and I do believe I exist. The world responds as if me being in it makes a difference, and I can obviously guide my own path to a considerable extent. But I haven't seen any sign of outside influence, of anybody arbitrarily breaking in and changing things. Doesn't mean it couldn't happen, and the whole thing shuts down tomorrow with a "Memory Full" message. But I think it is very unlikely.

I'm sure we in the future will become able to simulate whole universes. But we won't be succeeding in developing artificial intelligence before we have addressed it from a totally different angle. And once we actually figure it out, it doesn't really matter if we're in somebody's simulation or not, and there'll be no need to worry about whether robots will become smarter than us.

[ Knowledge | 2007-08-15 17:17 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

There's an improv game that's useful in getting beyond one's built-in mental censor. It's a well-known kids game, for that matter. There's an improv game that's useful in getting beyond one's built-in mental censor. It's a well-known kids game, for that matter.

You tell a story by each person providing one word at a time in turn, quickly.

"Joe" - "ate" - "some" - "rotten" - "shoes" ...

The thing is that most adults will attempt to censor themselves in such a game. In particular, most people will have some fear of saying something dirty, and will concentrate on NOT saying "fuck" or "ass" or something. Thus they'll hesitate, because they first need to filter or sort the things that actually come into their mind first. And the funny thing is that people will do that even if they wouldn't think twice about using the same words in a proper context. But if it is an improvised stream-of-consciousness kind of thing, we're likely to pay too much attention to how we'd be perceived, and how people will judge us if we say "balls" every time it is our turn.

And, indeed, if one gets over it and stops censoring oneself, the stories would probably be fairly filthy at first. But once one becomes ok with that, it changes again, and better stories develop.

Our sub-conscious is wiser than we usually are willing to admit. We too often try to be smarter than our instincts and impulses, by processing and filtering our first responses, so that they sound reasonable and logic. And that isn't always better.

"What's the first word that comes into your mind?"

That should take about a tenth of a second. Most people will take several seconds to answer. Not because they didn't have a word right away, but because they have to think about why you might be asking, whether their answer is a good one, and what you'll think about it.

That sort of need to censor what naturally happens is at the root of a lot of evils in society. Repressed urges, moralizing, standing up for things one doesn't really believe in. The old freudian belief that what is sub-conscious is crazy and evil and perverted. It really only is as long as you're repressing and denying it.

And it is also something that blocks our natural creativity. Good creative ideas are rarely the stuff you figure out logically. It is typically something that comes to you. But you'd need to be willing to let it, without second-guessing in advance what it might be.

[ Knowledge | 2007-08-15 17:16 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, July 6, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

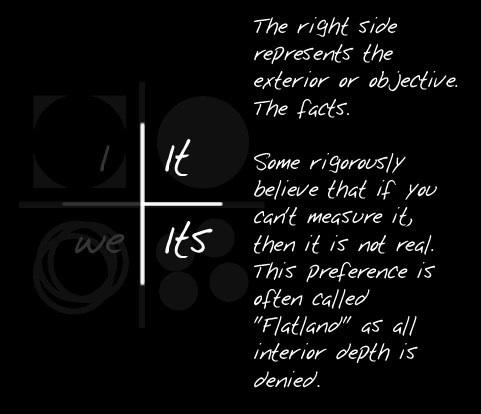

An excellent visualization of integral theory, according to Ken Wilber. (Via Chris Corrigan)

[ Knowledge | 2007-07-06 22:57 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, July 5, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

Matt Mower: Joel Spolksy has a good article on management books in which he quotes Michael Lopp:

The disagreement reminded me there are two distinct personalities when it comes to devising solutions to problems: Incrementalists and Completionists.

Incrementalists are realists. They have a pretty good idea of what is achievable given a problem to solve, a product to ship. They're intimately aware of how many resources are available, where the political landscape is at any given moment, and they know who knows what. They tend to know all the secrets and they like to be recognized for that fact.

Completionists are dreamers. They have a very good idea of how to solve a given problem and that answer is SOLVE IT RIGHT. Their mantra is, "If you're going to spend the time to solve a problem, solve it in a manner that you aren't going to be solving it AGAIN in three months." Hm, I guess that in that setting, I'd be a Competionist Completionist too. I'd often be a bit envious at people who are very pragmatic and who do things that work, from what is available, that can get out the door quickly, that end up succeeding, despite not being perfect. I'll tend towards trying to make the perfect thing, and then not getting around to getting it out the door.