| Hypertaskers do things faster but not better | 2004-09-05 23:59 7 comments |

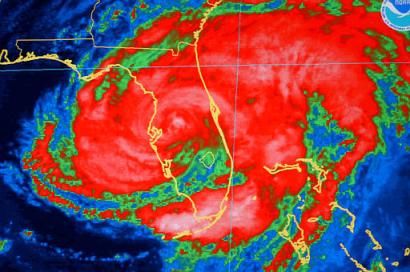

by Flemming Funch by Flemming FunchArticle in azcentral. Yeah, I'm probably one too. A hypertasker. Somebody who tries to do many things at once, who's always working, and who gets rashes if they don't have a fast internet connection close by. But doing many things at the same time isn't necessarily faster or even good for us, some researchers seem to say. "Hypertasking is excessiveness," says Patricia Arredondo, associate professor in Arizona State University's graduate counseling program. "It's overload in the sense of having your brain trying to respond to a number of stimuli at the same time, and that can really start to cost you."Excessiveness? Seems a little strong. But maybe they're right. Researchers argue that the brain isn't wired to do more than one thing at a time without loss of efficiency and quality.Hm, I'd say it isn't necessarily just too much. It is that certain activities might well dovetail together, and create a certain kind of synergy, where others don't. Like an example they give, one might very well go for a walk and talk with a good friend at the same time. One does several things at the same time, and yet one doesn't get stressed. But trouble certainly starts if we get anywhere close to trying to do time-sharing like a computer. You know, for years computers have pretended to do many things at the same time by slicing each second into many parts, and simply switching from task to task very quickly. Doing a little bit of one task, then a little bit of another, etc, and shortly return to the first one, and do a little bit more from where you left off. Might work for a computer, but that's the kind of thing that drives people crazy. So, if we have to talk brains, the problem might appear when we do several of the same kind of thing at the same time. Might not be stressful to walk and eat and juggle and talk at the same time, even if that is stretching it a little bit, because those are different systems. But if we need to talk to two people at the same time, we start getting inefficient and stressed. Just like if we're trying to taste two different foods at the same time. "How much can we push one part of the brain to do two things (at once)?" he asks. "Mother Nature didn't think we'd be sitting at a computer with four windows opened and the phone ringing. It's a cultural invention."So it isn't so much that we do strange and new things. It is more when we try to make several things occupy the same space when they can't. Some things can co-exist, if they complement each other, or if they operate on different wavelengths, so to speak. But if they're trying to use the same wavelength and they collide, then we start being just very busy and very inefficient. If we assume that we actually do need to deal with a much greater amount of continuous information than in past times, the task becomes to make it all appear simple and coherent. You know, a library isn't confusing, even if there's a million volumes in it. Reading 5 books at the same time, and not having time for it, that's confusing. Looking at a picture of the weather patterns on the planet, that typically doesn't stress us (unless there's a hurricane heading our way), but trying to predict the weather, while also trying to remember your shopping list, and keep track of your schedule, that might be confusing and stressful. The trick is to make it all fit together. To make information scalable, so that more of it doesn't have to mean that it collides. |