| Tuesday, July 4, 2006 |  |

|

|

|

At Tenth Dimension, you find a quick tour of the possible 10 dimensions of a universe based on string theory. Well, I don't know how scientific it is. Scientists who talk about 10 dimensions tend to bend over backwards to point out that they're not really the kind of dimensions that are useful for us to move in, but they're just sort of curled up in a very small place, of no practical significance to us, and only needed to make the equations add up. Which I tend to not believe, so I like it better this way. Rob Bryanton has a fun Flash animation that helps to visualize 10 dimensions. Essentially it is like the difference between 2-dimensional flatlanders, and our well-known 3 dimensions, which is something we fairly easily can visualize. So, we can imagine the same magic continuing in more dimensions. Seen from a lower dimension, somebody who moves in a higher dimension can do impossible things, like appear out of nowhere, or travel huge distances in an instant. Because higher dimensions fold lower dimensions. Just like you might find certain distances on a piece of paper (a 2D plane), but you can fold it in 3 dimensions, and bring any two of its points together, so you can get from one to the other, without traveling any 2D distance. It would be equally logical that you can do the same with time and 3D space, or with whole timelines, or universes of possibilities, once you use more dimensions. At Tenth Dimension, you find a quick tour of the possible 10 dimensions of a universe based on string theory. Well, I don't know how scientific it is. Scientists who talk about 10 dimensions tend to bend over backwards to point out that they're not really the kind of dimensions that are useful for us to move in, but they're just sort of curled up in a very small place, of no practical significance to us, and only needed to make the equations add up. Which I tend to not believe, so I like it better this way. Rob Bryanton has a fun Flash animation that helps to visualize 10 dimensions. Essentially it is like the difference between 2-dimensional flatlanders, and our well-known 3 dimensions, which is something we fairly easily can visualize. So, we can imagine the same magic continuing in more dimensions. Seen from a lower dimension, somebody who moves in a higher dimension can do impossible things, like appear out of nowhere, or travel huge distances in an instant. Because higher dimensions fold lower dimensions. Just like you might find certain distances on a piece of paper (a 2D plane), but you can fold it in 3 dimensions, and bring any two of its points together, so you can get from one to the other, without traveling any 2D distance. It would be equally logical that you can do the same with time and 3D space, or with whole timelines, or universes of possibilities, once you use more dimensions.

And if we assumed that the real reality is the 10 dimensions, rather than the 3, 3 1/2 we're used to, it potentially can change our perspective greatly. And, indeed, it might be an important element in our growth process that we're able to visualize these dimension, so that we maybe can start living more in the real reality, rather than insisting we're just flatlanders forever.

The website there seems to be an intro to a book by Rob Bryanton, called "Imagining the Tenth Dimension".

[ Patterns | 2006-07-04 12:00 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, June 8, 2006 |  |

|

|

|

These are always cool. Spanish Castle. Stare at the dot in the middle for 30 seconds.

Then, without moving your eyes, move the mouse over the image.

It will look like it's in color until you move your eyes.

[ Patterns | 2006-06-08 17:28 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, March 19, 2006 |  |

|

|

|

From Ross Mayfield, Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, outlining what he regards as the most important success factors:Access: open access, level playing field, transparency, equal access to information are attributes of any environment with positive outcomes

Connection: enabling individuals to connect and interact with one another. Market solutions, collaboration and wisdom of crowds.

Sense of ownership: skin in the game lets individuals feel there is an investment required to participate and accountability (e.g. reputation systems). (Via The Obvious)

[ Patterns | 2006-03-19 00:18 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, November 30, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

Douglas Rushkoff, except from a forthcoming book, Get Back In The Box: Innovation From The Inside Out, found on BoingBoing:In a renaissance society driven by the need to forge connections, play is the ultimate system for social currency. It's a way to try on new roles without committing to them for life. It's a way to test strategies of engagement without being defined by them forever. It’s a way to rise above the seemingly high stakes of almost any situation and see it as the game it probably is. It’s a way to make one’s enterprise a form of social currency from the beginning, and to guarantee a collaborative, playful, and altogether more productive path toward continual innovation.

And this play begins at work....

In their crude efforts to make work more fun, however, most companies are missing the point. Employers are busy installing foosball tables, hiring chefs, and building gyms for their increasingly disgruntled employees, but these are just ways of trying to make a bad situation more tolerable. (or to coax employees into spending long hours away from home) A foosball table is not the sign of a fun place to work; it's a glaring symbol that work is not fun and employees need a break. Why would they rather be playing foosball than doing whatever it is they've been hired to do?

Many have argued that it’s immature and idealistic to believe that everyone,or even a majority of people,should be allowed to enjoy their jobs. In the words of one dark New York TimesOpEd piece, "We're still just means of production....Work is often more bearable when we don’t, in addition to money, expect it always to deliver happiness." The same might be said for life itself, particularly when our duty to perform an economic function extends from what we can produce to what we can consume. Both work and life should be much more than "bearable."

Luckily, renaissances celebrate immaturity and idealism.

Ah, yes, play! Of course we should be able to enjoy our lives and our work, as it really ought to be the same thing. Crank up the renaissance!

[ Patterns | 2005-11-30 22:34 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Tony Judge wrote a paper about haikus and martial arts and strategic decision making. As usual, Tony's article is very deep and extremely well researched.

I've never really understood haikus. But this helps. Like, here's a little overview: The following comments on haiku benefit notably from the insights of Kai Falkman (The String Untouched, translation of En Orörd Sträng, Ordfront, 2005).

Haiku is essentially a very short poem depicting a specific experience in nature or in a human context. It is contrasted with a related form, senryū, which tends to be about human foibles while haiku tend to be about nature -- senryū are often cynical or darkly humorous while haiku are serious.

The traditional Japanese rules for haiku require the use of 17 syllables grouped into three lines composed of respectively 5-7-5 syllables. These rules are applied in a multitude of languages by a worldwide "haiku movement" (cf World Haiku Club; Haiku International Association) [more]. The emphasis is clearly placed on succinctness and appropriateness, requiring extremely careful consideration of the pattern of words used and the effect they together create. The superfluous is excluded. In the words of Antoine de Saint Exupery, "Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away."

Non-Japanese haiku poets have explored an even more abbreviated 3-5-3 form of haiku, as explained by Keiko Imaoka (Forms in English Haiku) in discussing the linguistic circumstances that necessitate shorter English haiku to be more loosely structured than Japanese haiku:

Over the years, however, most haiku poets in North America have become aware that 17 English syllables convey a great deal more information than 17 Japanese syllables, and have come to write haiku in fewer syllables, most often in three segments that follow a short-long-short pattern without a rigid structure. This style is called by some "free-form" haiku.

The core feature of haiku is an experience described in a concrete image designed to evoke the same experience in the reader. A good haiku is not simply a static description. Three valued attributes are:

* embodiment of a transformation -- possibly with a surprising ending and/or a lingering poetic atmosphere. This may be catalyzed by describing an impression characteristic of one sensory organ through words normally descriptive of the impression through another. Images may be connected in a surprising way, possibly by changing perspectives calling for movement between them. Thinking is surprised and changes direction. Metaphors are however rarely used in haiku, because the image is expected to speak for itself and not be compared with something else in order to be accentuated or transformed in significance. However it is consequently recognized as a form that is wonderful for metaphorical descriptions

* capacity to hold several layers of meaning that may be discovered or explored -- possibly subsequently on reflection, or over a period of time. This may be achieved by using a proximate image like a fractal to imply the larger context of which it is a detail. Indirect insight is typical of haiku.

* act as a container for deep meaning, as characterized by a sense of poignancy, being touched, existential tragedy, or inevitability beyond conventional frameworks. It offers a value-charged integrative perspective.

Stress is placed on the concreteness of the images. Purely abstract or intellectual concepts are not considered valid haiku -- irrespective of their conformity with the formal rules or the value of the experience they may engender. Meaningful insights overtly expressed are considered as an imposition, potentially alienating to the reader. This is an implicit aesthetic that is discovered by a receptive sensitivity rather than an invasive technique. A degree of detachment or distance is valued. Although the concrete images may be anchored in the immediate or distant past -- perhaps specifically associated with a season -- the effect sought is an experience in the present moment, the immediate here and now.

And then he touches on stuff like the "catalytic role of haiku in kairotic time". Kairos or Kairotic is a concept that's hard to define, but it refers to some kind of irreducible experiential singularity, and it can be seen in contrast to chronological (linear) time. Some kind of moment of clarity and truth. Which relates to haikus, and it relates to tao and martial arts, and to paradoxical states of pure being or of not-doing. You know, going beyond the mind and linear logical thinking, and just experiencing the truth of what's in front of you, or in you. And acting based on that.

But I still can't write a haiku. Well, let me try...

Words in syllables

meaning frozen into portable bits

understanding is wordless

Was that a haiku? Hey, that went pretty well. How about:

I am speechless

A world is there now

saying it all

or

Red, green, blue

Pixels light on my screen

Nothing is hidden

I like the 3-5-3 syllable thing best. [But my mind glazed over, and I didn't notice it said "syllable" and not "word", and I counted words] I also like the Bontos. Actually it is a great creative exercise to construct stuff like that, so let me try one of those:

Have your supper in the fridge

Cold food spoils less

Freezing might catch you a cold

Tempered balance makes your way

Ooh, I can't stop now.

Writing haikus to be strategic

Striving to be singularly decisive

Do I transform or just explode?

Nothing new was known before

[I forgot the syllable rules there too. Poetic license!]

OK, I'm going to push "Post" now. But, indeed, it would probably be wise to check if world leaders, large or small, can get themselves to write haikus. Anybody who only lives in the linear world of mind is likely to be dangerous.

[ Patterns | 2005-11-30 21:45 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, August 26, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

Tom Atlee mentions The Great Story and the work of Connie Barlow and Michael Dowd in integrating science and religion into a bigger view of life, the universe and everything, where there's no conflict between evolution and consciousness. He's a former evangelical preacher and she's a science writer. Here's an article called "No more trivializing God!". Tom Atlee mentions The Great Story and the work of Connie Barlow and Michael Dowd in integrating science and religion into a bigger view of life, the universe and everything, where there's no conflict between evolution and consciousness. He's a former evangelical preacher and she's a science writer. Here's an article called "No more trivializing God!".

Do you believe in life?

Well, do you?

This is an absurd question, yes? Of course! It simply doesn't matter whether we "believe in" life or not. Life is all around us, and in us. We're part of it. Life is, period. What we say about life, however, is another story. If I say, "Life is wonderful," or "Life's a bitch," or "Life's a jungle," you may or may not believe me, depending on your own experience and the stories you've heard from others. What we say about life - its nature, its essence, its purpose, its patterns - along with the metaphors and analogies we choose to describe it, are all open for discussion and debate. But the reality of life is indisputable.

This is exactly the way that God can be understood, and is understood from the perspective of The Great Story - that is, from the perspective of those who see the science-based history of cosmos, Earth, life, and humanity in a sacred, meaningful way. And this is precisely why the question, "Do you believe in God?", is a non-starter.

[ Patterns | 2005-08-26 21:50 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, June 22, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

This one in strange. I put it in the full article, so you don't get stuck in your head. Anyway, the instruction is simply to concentrate on the + for a few seconds This one in strange. I put it in the full article, so you don't get stuck in your head. Anyway, the instruction is simply to concentrate on the + for a few seconds

[ Patterns | 2005-06-22 17:08 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, May 24, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

Robert Cringely had a couple of articles recently, DayJet May Be the First Peer-to-Peer Airline and Jet Me to Work Robert Cringely had a couple of articles recently, DayJet May Be the First Peer-to-Peer Airline and Jet Me to Work

DayJet Software Could Revolutionize More Than Just Air Travel. Essentially about a private jet company called DayJet, which has made a piece of software that makes it economical to provide relatively cheap business flights from just about anywhere to just about anywhere in the U.S. on cheap jets that have seats for just 3 passengers. They plan on having between 40 and 300 planes like that. The big deal is their optimization software. All airlines have to do a big optimization calculation, to figure out how best to utilize their aircraft, and transport the most people to places they want to go, for the lowest cost. But even for a major airline, the number of planes and routes and destinations is relatively small, and they don't change their routes very often. What DayJet has in mind is a much huger set of optimization calculations, done not every month, but every time somebody wants to go somewhere. The use of the planes will change all the time, and any little airport might be used, as long as the jets can land there. So, the whole calculation needs to be done basically for each customer, in relation to whoever else wants to fly around that time. You know, it isn't economical to fly just one person, so the optimization will figure out how best to serve everybody and fill up the seats as much as possible.

I don't think I'll ever fly in one of those seats, so that's not why it is interesting. What's interesting is the general possibilities of optimizing a whole bunch of things, if you have the software and the computing power for it.

Our society is a rather inefficient machine in many ways exactly because we don't have very efficient means of coordinating what is available with what is needed.

If I have a book I've read and I don't need it any longer, why don't I give it to somebody else who'd like it, particularly if they live just around the corner, and they can come and pick it up this afternoon? Because we don't know of each other, that's why. And there's no good means for us to do so. I'm not going to go around and put up notices on the lamp posts for my book, that's too expensive in effort expended. And if everybody did that, there'd be too much information to wade through. But software could do it. It is a matter of representing what is available and what is needed in some kind of useful manner, and then it is an optimization problem.

Why don't everybody on a street share a small number of lawn mowers, instead of having to maintain their own? It could be much cheaper to share. The reason is that it is too much trouble to coordinate the sharing, and figuring how the right number of lawn mowers and the scheduling. In the absence of some kind of optimization program, it is just much easier to each have our own.

Why do I need to have my own bicycle or car? If I could always find an available vehicle standing close by, and it was reasonably cheap and somebody took care of the maintenance, it would probably be more economical for everybody that we shared. And, indeed, there are now companies that deliver that service in various major cities. Cars or bicycles with GPS systems, coordinated by optimization software.

Really, our whole society is not much more than one big optimization problem. We've got these resources, we've got these needs - how do we bring them together in the most optimum manner? On a micro level.

In a way the solution to that could be a synthesis of free market capitalism and centralized communism. Better than either of them. Both of them bog down because it is just too centralized and there's no good capability to give most people what they need, or to use their resources well. So the solution has been to just make up some product that a lot of people ought to want, and make a one-size-fits-all version of it, and market the hell out of it, and not worry about if it isn't perfect for everybody. Or, in the communist version, to decide what kind of appartment everybody ought to have, or what kind of bicycle, and then just manufacture the same for everybody, in a big dull centralized factory.

If we had the infrastructure for it, it could both open up a great many more business opportunities, and at the same time it can cheaply solve many social issues. As to the book I no longer need, I might either be happy giving it away for free, or I might participate in a business that gives me an appropriate amount of money for it. If I have a restaurant that throws away all the left-over food every day, it would be no extra trouble for me to let somebody come and pick it up and feed it to poor people. All based on that the communication infrastructure is very cheap and easy to use. And that it optimizes both the use of resources and the result or profit gained from their use. I might either want to get the most possible dollars for my book, or I might want to give it to whoever will have the biggest benefit for it. It is merely an optimization problem either way.

The way it will happen is probably that comparnies carve out a niche, delivering more personalized service more efficiently, and we start getting used to expecting custom solutions, rather than general solutions that don't quite fit. We'll start expecting that there will be public transportation in front of our door, rather than half a mile away.

It would be better if it were a transparent open-source system that did it, but competing business solutions would be a good start.

The more transparent, the better. It can potentially be a huge shift in how things are done. See, most traditional businesses are based on hiding from you what the optimum solution would be. In part because they might not know, but also because their economics are based on giving you roughly what they give everybody else, and making you believe that it is the best that is available. Imagine that instead you had your own optimizer, which was plugged into a vast and finegrained infrastructure, which pretty instantly could point out to you the shortest route between what you have and what you want.

[ Patterns | 2005-05-24 17:44 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, April 13, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

Various experiments have been done to try to figure out how people value things and make decisions. Psychologist Max Bazerman says that during the past ten years he has earned more than $17,000 by auctioning $20 bills to his MBA students at Northwestern University. In the course of almost two hundred of his actions, the top two bids never totaled less than $39, and in one instance totaled $407. Various experiments have been done to try to figure out how people value things and make decisions. Psychologist Max Bazerman says that during the past ten years he has earned more than $17,000 by auctioning $20 bills to his MBA students at Northwestern University. In the course of almost two hundred of his actions, the top two bids never totaled less than $39, and in one instance totaled $407.

Now, that's when it is very clear what you get for your money. A 20 dollar bill. Logic should dictate that no reasonable person would bid more than $20 for what obviously is a $20 value. But all sorts of other factors might enter into the calculation. The fun and excitement of the bidding, the prestige of being the winner, the expectation that there might be some kind of valuable hidden bonus, etc.

A similar, but somewhat more complex type of auction would be if you're not entirely sure of the value you're betting on. If, say, it is a glass jar full of coins, which you aren't allowed to count. If people make blind bids written down on paper, the average bid will tend to be less than the actual value, as most people are trying to avoid the obvious risk. But some people will over-estimate the actual value, so the winner of the auction would typically be somebody who ends up paying more than the actual value.

And then there's the particularly sneaky variant, the Entrapment Gam. Let's say that everybody who bids in an auction must pay the amount of their bid, whether they win or not, but you're allowed to continue over-bidding each other. People will start really low, like 0.50, as most people feel they can waste that. Bidding continues up to around $10 and pauses. Then the people who've bid $8 or $9 must decide whether they'll lose that or they'll continue. It will continue up to $20 when again there's reason for pause. One might realize that one now is likely to lose quite a bit. So maybe if one throws in a few extra dollars and wins, one will lose less, so it might be worth it. And it might go on quite a bit like that, as at each step one must evaluate whether one might avoid a loss by paying a bit more. Even if one ends up paying a lot more for the 20 dollar bill than it was worth. This was apparently the game Mr.Bazerman played with his students.

There might be surprisingly many situations in life that are similar to that scenario. Competitive sports, the making of business deals, buying a house, etc. You might have invested a certain amount of time and effort and money, and even if you know you won't get back the equivalent, you might think that just a little more would get you what you're going for and minimize the losses.

More here or here.

[ Patterns | 2005-04-13 23:06 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, March 17, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

Dee Hock Interview via Synergic Earth News. Dee Hock Interview via Synergic Earth News.You can probably remember the days when a check would often take weeks to find its way through the banking system. That was called "float." This float was used as an early form of venture capital. Now, stop and think about other kinds of float. Think about information float (this is what Beck is speaking about): if you go back just a few centuries, it took, for example, almost a century for the knowledge about the smelting of iron ore to cross one continent. That brought in the Iron Age. When we landed on the moon, it was known and seen in every corner of the world in 1.4 seconds. Think about technological float: it took centuries for the wheel to gain universal acceptance. Now any microchip device can be in use around the world in weeks. Think about cultural float: it used to take centuries for one culture to even learn about or be exposed to a tiny bit of information about another. And now anything that becomes popular anywhere in the world can sweep through other countries in weeks. Consider space float: in just one long lifetime, a hundred years or so, we've gone from the speed of the horse to interstellar travel. People and materials now move in minutes when they used to move in months. And even life float - the time it takes to evolve new life-forms - is collapsing with genetic engineering. What all this means is the loss of change float - the time between what was and what is going to be, between the past and the future - so the past then becomes ever less predictive, the future ever less predictable, and everything is accelerating change with one exception: our institutions. There has been no truly new concept of organization since the ideas of nation-state and corporation emerged several centuries ago. That's probably about right.

But, now, *float* was a lag between when something supposedly happened to when it actually happens, and, in particular, the advantage somebody can have from the in-between state. You put a check in the bank, and at some later point the money becomes available. And in the meantime the bank has some extra money available. And the person who made out the check has the money still available, even though he apparently has paid you. And they can do stuff with it, even though it in principle isn't there.

Dee Hock is trying to make some other point there, of acceleration. He's more talking about lag than about float. Really, the float thing is more interesting in itself, I think. Like, I'd say there's a life float between your birth and your death, which we certainly get a lot of milage out of. From the perspective of the evolution of nature it might be more interesting that we move on to the next, slightly improved, generation. Whereas, for us, the interesting part is the float in-between, not the end point.

If you travel from one place to the other, the in-between part is the float, if you use it for something. And maybe the journey is the best part. If we could teleport from place to place, there'd be no float, and we wouldn't experience journeys the same way.

Lots of things in our society are based on the advantages we gain from a float. Lots of economic activity is just that. You can have a job mainly because there's some space in between some kind of manufacturer or provider and their ultimate customers. If the owner of the operation could get rid of you, they probably would. But you earn a living from the steps in-between.

You can enjoy a movie or a book because there's a lag between the conception of that work and you "getting" the result of it. If you could just swallow a pill and get it all at one time, you'd be missing out on the real enjoyment, which is in the float, rather than in the result. I once took a speed reading course that allowed me to read 200-page novels in 15 minutes, with greater retention than before. But it was no fun at all, so I dropped the technique.

To be a float, the lag must be a good thing for somebody. Sometimes it isn't obvious. In the old days, where people had conversations over snail mail letters, it would maybe take a letter a week to reach me. That might make me impatient, or on the other hand, it might give me breathing room, as I'd have no obligation to write my next entry before I've received the next answer. I could get a lot of things done in that time. And I'd treasure my letters more.

So, in the speedy internet and cell phone age, there's much less float available. So, despite the obvious advantages of more instant communication, we're missing all the stuff we could do with the float or in the float.

It is in the spaces in-between stuff that life often happens. In the gaps, in the cracks. The good parts often happen as side effects. What happens in the periphery might be as important as what happens in the focus of attention. So, it is important that we don't weed out all the gaps in the name of progress. Or there's no float for life to happen in.

[ Patterns | 2005-03-17 13:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, February 17, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

Article in Wired, Revenge of the Right Brain, by Daniel H. Pink, talks about how Right Brain qualities seem to be more and more what we need. Article in Wired, Revenge of the Right Brain, by Daniel H. Pink, talks about how Right Brain qualities seem to be more and more what we need.Until recently, the abilities that led to success in school, work, and business were characteristic of the left hemisphere. They were the sorts of linear, logical, analytical talents measured by SATs and deployed by CPAs. Today, those capabilities are still necessary. But they're no longer sufficient. In a world upended by outsourcing, deluged with data, and choked with choices, the abilities that matter most are now closer in spirit to the specialties of the right hemisphere - artistry, empathy, seeing the big picture, and pursuing the transcendent.

Beneath the nervous clatter of our half-completed decade stirs a slow but seismic shift. The Information Age we all prepared for is ending. Rising in its place is what I call the Conceptual Age, an era in which mastery of abilities that we've often overlooked and undervalued marks the fault line between who gets ahead and who falls behind.

To some of you, this shift - from an economy built on the logical, sequential abilities of the Information Age to an economy built on the inventive, empathic abilities of the Conceptual Age - sounds delightful. "You had me at hello!" I can hear the painters and nurses exulting. But to others, this sounds like a crock. "Prove it!" I hear the programmers and lawyers demanding.

OK. To convince you, I'll explain the reasons for this shift, using the mechanistic language of cause and effect.

The effect: the scales tilting in favor of right brain-style thinking. The causes: Asia, automation, and abundance.

And he goes on to explain that. I don't know if he makes a great case for it, or if The Conceptual Age is the best term. But, I agree, a different age is emerging, where it doesn't do it just to be rational and to have the right information. More dimensions are needed. And there's too much information, and not time enough to analyze it all rationally. So we have to resort to more effective methods of dealing with complexity. Which, interestingly, to a large degree is intuition, feelings, exploring patterns in artistic or playful ways, rather than just logically.

The plus side could be that we'll tend to deal with the whole thing, rather than fragmented pieces of information. The minus side could be that we're more easily fooled, because we act on appearances and emotions, and don't get around to analyzing the facts at hand.

So, different qualities than before become critical. Being able to know right from wrong, without analyzing the data. I.e. being in touch with your own intuition, your inherent abilities to know things, even in the absence of facts. Sometimes you can make better decisions if you don't let yourself be distracted by facts. But lots of people are very bad at it, and get distracted by superficial signs, to make decisions they wouldn't have if either they knew the facts or they were in sync with their own senses.

And the Information Age isn't exactly going away, but rather transforming into something else. It won't be so much about having an edge by having access to better information than your competitors, as most information will be generally available. It will be more about what you do with masses of information than what you do with little chunks of it. More about the forest than the trees, more about the landscape of information than about the facts.

Anyway, back to the guy's article, which ends like this: Want to get ahead today? Forget what your parents told you. Instead, do something foreigners can't do cheaper. Something computers can't do faster. And something that fills one of the nonmaterial, transcendent desires of an abundant age. In other words, go right, young man and woman, go right.

Cool. So, we could say it is a change of focus. What before was to look outside for work and jobs and positions, maybe becomes to go inside and be inspired to do what you're here to do. Which becomes successful if one at the same time connects up with the heartbeat of the bigger, complex society. Plugging into the zeitgeist, the desires, the ebbs and flows of human attention. Where before, what you did had rather little to do with neither YOU nor with what the world needed - that now becomes all important. That *I* am in it, and that it rides on some kind of wave within the state of the world. Don't know if I can come up with a better word for it. Integral Age. Complex Age. Or Virtual Age, but that gets into another angle. Or maybe Conceptual Age is actually pretty good, as it encompasses several of those aspects. What a concept.

[ Patterns | 2005-02-17 15:28 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, November 15, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Well, I've mentioned this kind of thing before. And now we can test it on you. Here's a video. It is a 7MB java thing, so it will take a little while to load. And here are the instructions: You are only allowed to watch it once. Seriously, do not cheat! In the video you will see a group of basketball players, some in white and some in black passing two balls around. Your goal is to count how many times the ball is passed by those wearing white shirts. It’s that simple. Remember, count just the passes of the ball by those wearing white. Once the movie is over, write down the number of passes you have counted. And, once you've done that, go on to step two. That's all I can say. Watch the white players, count the passes of the ball, and go on to the page where you can see how well you did. (via MetaFilter)

[ Patterns | 2004-11-15 02:07 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, September 20, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Strange, there's only two pages of matches right now in Google on the term "Evolutionary Triggers". I didn't think it was such a well-kept secret. Anyway, it is a term that appears in evolutionary biology, like here talking about the surprising explosion in complex lifeforms in the Cambrian era, a little more than 500 million years ago: Strange, there's only two pages of matches right now in Google on the term "Evolutionary Triggers". I didn't think it was such a well-kept secret. Anyway, it is a term that appears in evolutionary biology, like here talking about the surprising explosion in complex lifeforms in the Cambrian era, a little more than 500 million years ago: The appearance of such a large range of body plans and life strategies at the base of the Cambrian in an apparently short space of geological time has intrigued palaeontologists for many years. There is still a great deal of speculation as to what caused or triggered the metazoan 'explosion', and why it happened when it did after 3 billion years of potential evolutionary time. It seems obvious that something must have changed or reached a critical level favorable for the building of large, complex bodies and the construction of hard skeletal material. The theories of what such evolutionary triggers may have been can be split into extrinsic or external environment factors, and intrinsic or internal biotic factors. So, something happens which maybe breaks a previous equilibrium, and suddenly it becomes advantageous for new things to develop. Of course something needs to be present in the first place which is capable of evolving. But then a trigger event or circumstance might inspire or influence it into suddenly evolving a whole lot.

I'm not sure if it is an idea that is necessarily popular with the kind of evolutionary biologists who believe that evolution is blind and random. But I don't really care. What I find most fascinating is the use of the meme in systems in general, including human systems.

I've noticed it time and again with people. If we're stuck in the same familiar routine, in the same familiar circumstances, in the same self-consistent worldview, we have a hard time changing. But if we're pulled out of those circumstances, or something drastically changes around us, or something goes over a threshold, change is suddenly much easier. And that is often what at first glance seems unpleasant circumstances that facilitate it. We get thrown out on deep water, or our world falls apart, and suddenly we might discover that we can change quickly, and sometimes for the much better. But we wouldn't have chosen it consciously from within our familiar old frame of reference. It takes a trigger. Sometimes that's somebody yelling at us. Sometimes it is a wise person who doesn't buy into our worldview who knows exactly where to put their finger. Sometimes it is something unexpectedly wonderful that happens that shakes us out of our skull.

Some systems thinking stuff from a page by Paul Herbig:Systems evolve when they reach a sufficient level of complexity, have flexible feedbacks between their components, are exposed to a sufficiently rich and constant energy flow, and when their normal functioning is disturbed. ( Laszlo 1985)

It is this factor of disturbance that is the evolutionary trigger for systems. If it is below the critical level, the systems normal feedback buffers it out and a return to stability with no evolutionary change occurring. If it surpasses the critical level, the feedback cycles are disrupted and the previous system vanishes and decomposes to more strongly bound components to another stable level. But just at that critical level, it is moved out of normal flow to another level. When that critical level is reached, a freedom of choice occurs, a bifurcation, and a new system diverges from the old. The evolutionary change I'd be most interested in would be some rapid positive changes in the collective consciousness of humankind. You know, the kind of changes that might make us suddenly realize we can live in peace and work together and have a great time at it. The kind of change that would henceforth make it impossible for a few misguided wackos to mess things up globally. Because the rest of us would actually be working together. Doing what is needed, what we're inspired to do, what is fun to do, and what works.

Could happen. Not terribly utopian either. Incremental change isn't going very well. The world, however off kilter it is, is trying hard to continue on the course it is on, and will tend to resist reasonable gradual attempts of changing it. There's just too much invested in the status quo, and so many reasons why it can't be any different. What is needed is a whack that is hard enough that it knocks us into a different space, where we actually notice we have the freedom to choose something different. Hopefully it can be a whack that isn't too devastating. It could very well be something obviously wonderful. No reason it shouldn't be. But it has to be a trigger that tips a lot of scales, and makes it impossible to remain the same.

[ Patterns | 2004-09-20 23:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, August 30, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

On the subject of Intimacy Gradients in Social Software, Chris Allen expands the discussion with much good detail. Like, directly from the horses mouth, from A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander: On the subject of Intimacy Gradients in Social Software, Chris Allen expands the discussion with much good detail. Like, directly from the horses mouth, from A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander:Pattern #127 - Intimacy Gradient:

Conflict: Unless the spaces in a building are arranged in a sequence which corresponds to their degrees of privateness, the visits made by strangers, friends, guests, clients, family, will always be a little awkward.

Resolution: Lay out the spaces of a building so that they create a sequence which begins with the entrance and the most public parts of the building, then leads into the slightly more private areas, and finally to the most private domains. That's very lucid. But however much it makes sense for physical buildings, it might not be useful in the same way for online spaces. As I mentioned earlier, the ability to easily link deep into just about anything short-circuits any hope for a gradual build-up of intimacy, as one works oneself deeper into more private areas. If you can go there in one link it might not feel any more intimate than the places intended to be very public.

Adina Levin also returns with some new angles: I suspect that the design principles for intimacy gradient are going to be different online than in 3d, and efforts to mirror 3d privacy patterns literally will be ineffective, just as interfaces mimicking 3d stores and offices don't work.

In 3d, the markers of privacy relate to

* property markers: my lawn vs. public sidewalk and street

* physical access: door and gate; bedrooms in back or upstairs

* visual and auditory access: conversation areas around a corner, with an insulating wall.

These design patterns designate ownership/membership, and different levels of physical access.

Online, there are different design patterns for signifying intimacy. Physical interference is less of a problem, while social accessibility takes some consideration. And she mentions some of the things that might mark intimacy in online "places", like the presence of personal information, pictures, related sites, recent changes, and more. All stuff that elaborates the context, and makes the participants more real. But, hm, is that really intimacy? Maybe. Makes me think, at least...

Calling it "markers" reframes the discussion a bit. In a house, it is not a requirement that the private spaces REALLY are harder to get to than the public spaces. But the sequencing and the appearance of them being more hidden will make you feel like respecting the arrangement. If you really wanted to, you might very well crash in through the bedroom window faster than you could walk through the entry hall, the living room, and the bedroom door. But all those elements act as markers that tell you that it wouldn't be right, and most normal people respect that. We could say that the space and the walls and the sequencing of rooms merely are markers. Which hint at a certain meaning of that which they mark. Like an implied meaning of privacy or public-ness.

Now, the object is how to establish markers in online settings that will imply certain kinds of meaning to visitors, and inspire certain types of behavior. For example:

Is it an intimate place where one can talk more openly and feel safe doing so without being attacked? Or is it a public place where one naturally would have one's guards up a bit, and expect to be accosted by random strangers?

Is it a place where one can leave some things around, and expect to find them again when one comes back? Or is it a place where thieves and vandals are to be expected, so one shouldn't count on anything staying in place?

Is it a place of continued, sustained work, gradually progressing, so you can come and check on progress at regular intervals? Or is it a place that is in the moment, that you need to experience while you're there, and it might be totally different next time you come back?

It is a place that is owned, somebody's property, or is there at least somebody obviously on-duty, taking care of it? In that case you might expect that they'd quickly clean off any grafitti you leave, so it might not be worth the trouble. Or if the ownership is too vague, or nobody's taking care of it, maybe you'll expect you can get away with whatever you do there.

Does it seem to be a place where important and serious work gets done? Or something that is just to pass time, and of no real consequence?

I can think of markers that indicate these various things. But an instant wrench thrown into any such attempts is the possibility that some automatic spam bot will not care, and is able to post anything whatsoever to any page that has a form for submitting something. It is a bit like when you leave your cellphone on in the movie theatre. Somebody who doesn't know where they're calling might disturb the peace. But there are solutions to that, of course. You might require registration and login, or make people type in characters from a graphic. That's probably a problem that can be overcome. So, what kinds of markers apply to real people?

The picture and name of a caretaker of a page will easily mark that the page is being taken care of, and indicates that it probably isn't just a free-for-all. Example: an about.com page that has an owner/editor.

Indications of goals, rules, a time-line, milestones, accomplishments, outstanding issues, etc., will indicate that somebody is trying to do real work there. Example: a sourceforge open source programming project.

An indication of a page being your personal page, like your preferences or a My[Something] page will mark that only you can change it, and that it is safe to do so, and whatever you do will be the same when you come back. Example: your Ryze profile.

A requirement of registration, and a list of members of the group which is rather small will tend to indicate that the space is somewhat intimate and that one safely can talk openly. That is often false, as even known people might disagree with you and attack you, so those are not very good markers. That one is harder.

A blog will surprisingly often indicate a fairly intimate and safe space, at least for the owner, despite that usually anybody can post comments. Because there is one owner, and they are in control, and you get to know a lot about them, so you can fairly easily determine what it is safe to say to them. One marker is a large amount of fairly personal and consistent information.

As to group-oriented spaces, there are more difficulties. The best markers for whether it is a fairly safe and intimate place is probably a continous and coherent body of work over some time. I.e. the group has worked with a certain focus for some time, and you can see what has happened, and the tone people have communicated with. If there's then also a visible care-taker, and a required registration and visible member list, and some clear rules, even better. But if there's no focus, or the activity isn't consistent, or it isn't clear who's there, it is probably less safe and intimate. But that's all a little too fuzzy. Hard one.

Clearly, context needs to be visible to be able to ascertain how intimate the space is. How long has the space been here? Who's here? How long have they been here? How much have they contributed exactly here? What are they working on? Are they working together? What has been accomplished? Where is it? What is projected for the future? The more detail there is, the more consistent it is, and the more all participants are inter-connected with each other, the more intimate the space probably is.

[ Patterns | 2004-08-30 23:20 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, August 24, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

From Jerry Michalski: From Jerry Michalski:Today at Tom Munnecke's GoodApples workshop in NYC, our lively moderator Izzy Gesell mentioned in passing the thirty-some fundamental plot lines. I couldn't help asking Google, which swiftly steered me to The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations by Georges Polti, and The 36 Plots site by Loren Miller, which lists them all. And here they are: - Supplication - Persecutor, Suppliant, a Power in Authority

- Deliverance - Unfortunates, Threatener, Rescuer

- Revenge - Avenger, Criminal

- Vengeance by Family upon Family - Avenging Kinsman, Guilty Kinsman, Relative

- Pursuit - Fugitive from Punishment, Pursuer

- Victim of Cruelty or Misfortune - Unfortunates, Master or Unlucky Person

- Disaster - Vanquished Power, Victorious Power or Messenger

- Revolt - Tyrant, Conspirator(s)

- Daring Enterprise - Bold Leader, Goal, Adversary

- Abduction - Abductor, Abducted, Guardian

- Enigma - Interrogator, Seeker, Problem

- Obtaining - Two or more Opposing Parties, Object, maybe an Arbitrator

- Familial Hatred - Two Family Members who hate each other

- Familial Rivalry - Preferred Kinsman, Rejected Kinsman, Object

- Murderous Adultery - Two Adulterers, the Betrayed

- Madness - Madman, Victim

- Fatal Imprudence - Imprudent person, Victim or lost object

- Involuntary Crimes of Love - Lover, Beloved, Revealer

- Kinsman Kills Unrecognised Kinsman - Killer, Unrecognised Victim, Revealer

- Self Sacrifice for an Ideal - Hero, Ideal, Person or Thing Sacrificed

- Self Sacrifice for Kindred - Hero, Kinsman, Person or Thing Sacrificed

- All Sacrificed for Passion - Lover, Object of Passion, Person or Thing Sacrificed

- Sacrifice of Loved Ones - Hero, Beloved Victim, Need for Sacrifice

- Rivalry Between Superior and Inferior - Superior, Inferior, Object

- Adultery - Deceived Spouse, Two Adulterers

- Crimes of Love - Lover, Beloved, theme of Dissolution

- Discovery of Dishonor of a Loved One - Discoverer, Guilty One

- Obstacles to Love - Two Lovers, Obstacle

- An Enemy Loved - Beloved Enemy, Lover, Hater

- Ambition - An Ambitious Person, Coveted Thing, Adversary

- Conflict with a God - Mortal, Immortal

- Mistaken Jealousy - Jealous One, Object of Jealousy, Supposed Accomplice, Author of Mistake

- Faulty Judgment - Mistaken One, Victim of Mistake, Author of Mistake, Guilty Person

- Remorse - Culprit, Victim, Interrogator

- Recovery of a Lost One - Seeker, One Found

- Loss of Loved Ones - Kinsman Slain, Kinsman Witness, Executioner

That's fun. Well, not exactly fun for the characters in those plots, but presumably, like most good stories, things get worked out in the end. And good stories often involve some kind of big problem or wrong that, against significant odds, gets worked out or reversed or balanced out along the way. An endless number of novels and screen plays and games could me made from those models. One might even imagine that it would be possible to automatically create reasonably gripping stories from such a basis. Oh, takes other elements too of course. But life probably consists of more archetypes and archetypical scenarios than we'd usually be willing to admit.

I also get to think of the power of metaphors, and of a great book, which I unfortunately don't remember the details of right now, and I'm away from my library. As a therapeutic tool, stories and metaphors can be very powerful. See, we all have an innate sense of how good stories are supposed to progress. We can not always express it, but we recognize it when we're presented with it. There are many kinds of stories, but each one has a certain kind of fundamental structure. Now, think of somebody who has a personal problem that seems unsolvable to them, and which is resistant to most direct attempts of helping them change it. Imagine that a wise and resourceful observer recognizes the structure of their problem, and presents them with a story. A story which happens to have the very same fundamental structure as their problem, but very different content, and a story which happens to get resolved in the end, like good stories do. If the person can get sufficiently involved in that story, following along with it, noticing that the difficult situations get resolved, something magical can happen. Without consciously noticing what happened, they might suddenly find that from the depths of their subconscious they suddenly also have the resources for resolving their own particular situation. The structure of a story from a very different setting might transfer to their particular setting, despite any "good" reason that it shouldn't. There's just something compelling about stories that get finished.

Knowing the archetypical structure of many fundamental human scenarios can thus be a tool for much more than just writing entertaining stories. I'm sure there are many more than 36, though. And some of them are more fun.

[ Patterns | 2004-08-24 22:34 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, August 8, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Benoît Mandelbrot is the guy who "invented" fractals. I.e. the mathematical formulas that made them visible in pretty patterns. Benoît Mandelbrot is the guy who "invented" fractals. I.e. the mathematical formulas that made them visible in pretty patterns.

He's obviously a smart guy, and now he wrote a book about patterns in financial markets, and part of it is quoted as an article in Wired. Now, when I first saw the link to it, I got excited. Actually applying the best possible math to really understand how to economy works - that would be a splendid idea. Maybe we can calculate how we maximize that everybody gets what they need, and creativity and good work is encouraged the most. That's just a matter of optimizing how the game is played. Well, I say "just", but I don't know how to do it. But with a study of patterns, and simulations, and lots of math, that ought to be possible.

Turns out it isn't about that at all. Seems he's rather appealing to the wizards of wall street to do better simulations of the stock market. And he's appealing to "regulators" to regulate global bank reserves. Oh, I'm sure he knows what he's talking about ...within a certain scope. I just think the real story is way outside that scope. I don't think the Bank for International Settlements have in mind suddenly being regulated. Their little corner of Basel have by treaties been beyond the law and scrutiny of any government for a long time, and I don't see why they would change that. And I have no doubt that they already are spending many billions of dollars each year on computer simulations. And, no, I don't think it is just of the stock market and the employment rates. But what do I know?

Anyway, he does say some quotable things:A well-managed corporation devotes some portion of its research and development budget to basic research, in fields of science that underlie its main business. Isn't understanding the market as important to the economy as understanding solid-state physics is to IBM? If we can map the human genome, why can't we map how a man loses his livelihood? If millions can contribute a few cycles of their PCs to the search for a signal from outer space, why can't they join a coordinated search for patterns in financial markets? Well, yeah, why not. Or rather, why can't we run better simulations of our overall society? Or, rather, why can't WE do that, rather than just the supercomputers of some central central bank who isn't sharing what they find?

The first thing we'd notice would probably be that there's a curious absence of know-how on how to do that, and I lot of experts who'll say it is impossible or uncessary. All the more reason for somebody to do it.

OK, it isn't easy, as human factors play a big part. But we really ought to be able to evaluate alternative scenarios for how we structure our society economically. With an eye towards maximizing the lasting benefit for 6.4 billion people, not to mention the planet we live on. As opposed to just scenarios to help capital holders hold on to their capital.

[ Patterns | 2004-08-08 20:25 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, July 29, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

This is the text from a few slides of a presentation by Joel Barker called "Leadership Lessons for the 21st Century". It is obviously slides to go along with a speech he gave, which I didn't hear. I did hear him talk about quite similar things a few years ago at the World Future Society's conference. Or, actually, there he was concentrating on the lessons from diversity in ecosystems.

The Verge and Innovation - Where does radical innovation happen in nature?

- Old answer: in the richest part of the ecosystem

- where there's the greatest competition |

|

Or the most complex system of collaboration, whichever way you prefer to look at it. The right kind of diversity makes interesting systemic synergies happen.

The New Answer - at the Verge - A verge is where something and something different meet

- It is as far away from the center as you can get!

- In ecosystems it is where two ecosystems intersect

- ocean and seashore

- forest and prairie

- river and desert |

|

Actually his slide accidentally said "river and dessert". That would be even more strange, of course. But think about tube worms living in 600 degree sulphuric water by vents on the ocean floor.

The Safety of the Verge - Having a strange environment very near triggers an organism to explore it for possible advantage

- In that exploration, it discovers that novel changes give it advantage, i.e. innovations

- And, most importantly, it is safer to fail because you are not interacting with competitors

|

|

Barker is a management consultant and speaker. So, the point is obviously that we can draw lessons from how nature works, and apply them to our endeavors. Say, to business. Some juicy hints there for fostering innovation. Explore the edges, the boundaries. Hook up with the strangeness out there, and learn something new. And you'll have an edge, because there's no competition there yet. Good stuff.

[ Patterns | 2004-07-29 14:31 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, July 28, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Yahoo Dictionary: Yahoo Dictionary:Paradigm: A set of assumptions, concepts, values, and practices that constitutes a way of viewing reality for the community that shares them, especially in an intellectual discipline. An important word to know. The Paradigm Web:The word "paradigm" was originally one of those obscure academic terms that has undergone many changes of meaning over the centuries. The classical Greeks used it to refer to an original archetype or ideal. Later it came to refer to a grammatical term. In the early 1960s Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996) wrote a ground breaking book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, in which he showed that science does not progress in an orderly fashion from lesser to greater truth, but rather remains fixated on a particular dogma or explanation - a paradigm - which is only overthrown with great difficulty and a new paradigm established. Thus the Copernican system (the sun at the center of the universe) overthrew the Ptolemaic (the earth at the center) one, and Newtonian physics was replaced by Relativity and Quantum Physics. Science thus consists of periods of conservatism ("Normal" Science) punctuated by periods of "Revolutionary" Science. Even more important is finding out how to get these things changed, preferably faster than waiting around for the people with the old views to die. From the same source:Paradigm Shift: When anomalies or inconsistencies arise within a given paradigm and present problems that we are unable to solve within a given paradigm, our view of reality must change, as must the way we perceive, think, and value the world. We must take on new assumptions and expectations that will transform our theories, traditions, rules, and standards of practice. We must create a new paradigm in which we are able to solve the insolvable problems of the old paradigm. More good info at Wikipedia. Anyway, so, get that. A paradigm is on its way out when it no longer solves the problems it is meant to solve. Or, rather, it should be on its way out, and a better paradigm should replace it, which better solves the present problems. For various reasons, that might not happen readily. There are people with a vested interest in the old paradigm, who have based their careers on it. And we all have habits that might be difficult to change, including habits of thinking. And we might not really know what the new, better paradigm should be. Even if we bump into it.

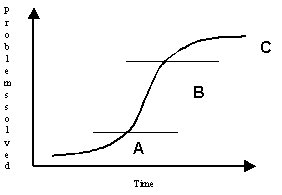

Paradigms usually don't start working well right away. And they don't suddenly just stop working either. One way of looking at the life cycle of a paradigm is with a diagram like this. There's a starting period, A, when the paradigm is still being developed, and one hasn't quite figured out the best way of using it yet, so it isn't all that impressive how well it solves problems. Then there's a phase B, where it all has been streamlined, and the paradigm accepted, and it solves lots of problems. Finally, phase C, it slows down, or might eventually drop. Maybe the problems get harder, or they change fundamentally. That's probably when somebody might start looking for better paradigms. Would be better if they did it in phase B, so that there would be time to develop the new approach. But most people wouldn't be looking at that time. Paradigms usually don't start working well right away. And they don't suddenly just stop working either. One way of looking at the life cycle of a paradigm is with a diagram like this. There's a starting period, A, when the paradigm is still being developed, and one hasn't quite figured out the best way of using it yet, so it isn't all that impressive how well it solves problems. Then there's a phase B, where it all has been streamlined, and the paradigm accepted, and it solves lots of problems. Finally, phase C, it slows down, or might eventually drop. Maybe the problems get harder, or they change fundamentally. That's probably when somebody might start looking for better paradigms. Would be better if they did it in phase B, so that there would be time to develop the new approach. But most people wouldn't be looking at that time.

Joel Barker explained all of that really well, in a (very expensive) video and a (cheap) book. Several books, actually.

It is worthwhile to learn to see paradigms. So one can realize which ones one is stuck in, and so one can recognize the alternatives when one sees them. Both are hard. The well-worn paths of the human mind makes it difficult to see where else one could go.

Imagine that changed. That we evolved a bit and we always had a consciousness of what paradigms we were living in, and the myriad of other possibilities. Meta-humans.

[ Patterns | 2004-07-28 21:40 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, July 27, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Bernie DeKoven on e-playing and e-learning, via Doc Searls: Bernie DeKoven on e-playing and e-learning, via Doc Searls:I call it "learning by dying" and I think it's probably one of the most powerful contributions that eplaying has for elearning. The most fun and efficient way to master most computer games is to play until you get killed, and remember what killed you. You usually have a few lives to sacrifice to learning. And you can always start over. This approach to learning has given most young people so much confidence in their competencies that, when confronted by a new game or new technology, they hardly ever need to look at the instructions. That is indeed a different way of learning. Different from what I grew up with. My kids quite obviously prefer to learn a different way than I. Is it better? For some purposes it obviously is. And more fun. And maybe the educational system needs to better catch on to this whole thing.

Learning by Dying. Something kind of disturbing about that, though. Although, it is maybe closer to how nature works than any other educational system we've cooked up. Maybe we need to recycle ourselves more often. Speed up evolution.

Anyway, he also quotes from an article Online Learning and Fun, about:"...the concept of meaningful failure. A player learns through trial and error and especially from mistakes, trying a different approach to accomplish the task at hand. Games often provide multiple opportunities and methods for a player to succeed. If a player fails using one approach, there are other ways to solve the problem. e-learning can leverage this gaming approach, offering multiple means of solving problems to encourage exploration and learning from failure." Yeah, we need to fail more often. Fail in the good and meaningful way. Gotta know how to die, and be reborn, stronger and smarter. The faster the better. We're too stuck in things we really ought to drop and move on from. Go to the next level.

[ Patterns | 2004-07-27 20:05 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, July 24, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Tom Munnecke, in commenting on Mass Listening, says: Tom Munnecke, in commenting on Mass Listening, says: Listening is also part of the "Yes-And" Improv dialog form I am now researching. Improv actors have to listen to their partners... what a concept. They also learn that accepting a partners' offer is different than agreeing with it. And that "yes,but" creates a zero sum conversation, while 'yes, and' opens up a much more richer dialog. Ah, yes, thanks for reminding me. I've done Improv too. You know, improv is when one creates a reality together on the spot, which hopefully becomes interesting and maybe funny. One of the ground rules is to accept whatever anybody else brings into it, and build on it, rather than reject it if it doesn't suit you. If I come into a scene, and I had in mind that I was going to be Doctor Shtrumpfswanz, head of the psychiatric department, and somebody else beats me to it and greets me with: "Oh, the plumber, I'm glad you finally came!" - then I'm the plumber from then on. No use protesting and rejecting it, it would just ruin the scene. If somebody establishes that there's a table in the middle of the room, then there's a table in the middle of the room, no matter what clever alternative ideas I might have had. The answer is "YES, AND..". I must build on whatever everybody else have brought into the scene. For that matter, good improv comedy arises exactly when the participants are willing to accept what is there, and some rather surprising elements might have been brought together. And you find yourself playing tennis in a submarine, or something else you might not easily have found logical.

I frequently go back to find wisdom in the things I learned in improv. There's really a lot there that applies to life in general.

Improv works great when one is totally in the moment. One accepts everything that is there, and addresses it as real, and at the same time one channels something that might take it in just about any direction, and one has to track continuously with several other people who do the same. The moment you get stuck in your own head, getting bright ideas about what is supposed to happen, and not noticing what is really happening, it stops working. It is sort of an odd thing, like starting sentences without having any clue how they'll end. And finding that things often are better that way. Certainly more funny.

Anyway, I think Tom's point was how that kind of thing applies to regular conversation, and relating to others. The Yes-And principle. Hmm, I actually hadn't considered completely doing that in regular life.

What if I just accepted everything anybody brought into the scene? Hm, that's actually a hard one.

I was once waiting for a while in the reception of an insane asylum, as that also happened to be where one kept people who were on drug rehab. And some of the, eh, residents came up and chatted with me. Which was delightful. You know people who see spiders on the wall, or tell about their life as tabloid journalists or secret agents. None of which really was happening, but I didn't mind at all jumping into their reality and accepting what they were experiencing. Now, the psychatrist on the other hand was somebody it was no fun to speak with, but that's another matter.

But in the real world? What if I accept somebody else's reality, and just build on it, and see where it goes, rather than introducing any kind of "Yes, but ...[you're wrong]" kind of thing. I suppose that would really make for good listening. You allow them to reveal more of their reality, and see where it goes.

For that matter, that has also been a key ingredient in my work as a counselor. I'm not going to argue with the client. Whichever way they experience the world is what we'll start with. OK, my job is to help them transform it into something that is more useful to them. But I don't do it by negating what they believe. I do it by a kind of conversational judo. I use the force of their own worldview, and the way they structure themselves, to lead them towards transforming themselves. Works very well, if you manage to stay neutral, and you know something about how these things work.

But I must admit that I don't necessarily do that in a normal conversation. Oh, I'm open to many views, and I can leave many of them alone, but there will always tend to be some kind of tendency towards bringing you over to my view.

Can I give that up in all circumstances? Maybe. I do notice that it almost never works to negate what other people really believe in. It rarely works to try to WIN an argument by methodically destroying the 'opponents' statements. And yet that's what most of us do half the time.

It is the 'shoulds' that get in the way most of the time. How somebody else 'should' think, and how things 'should' be. But the fact of the matter is usually that they actually aren't like that. The 'shoulds' are a mental hallucination we superimpose on reality. Really, the best way of changing anything is to accept what is already there, and then look for available paths of maybe helping it change into something else. And if there are no available paths, you might just allow things to remain the way they are.

Interestingly the more in balance we ourselves are, the less we feel a need for correcting everybody else's worldviews. The more enlightened you yourself are, the less you are obsessed with making everybody else be like you. Ironically, as we could say you had all the more reason to do so, if you've found some kind of nirvana that most others haven't.

But maybe the bigger truth is that the world really would work better if we could accept different world views, and simply allow them to evolve naturally. And maybe life would be more interesting and entertaining if we dropped the mistaken idea that we all live in exactly the same world, and we're supposed to live by the same rules.

[ Patterns | 2004-07-24 17:07 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

<< Newer stories Page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Older stories >> |