| Wednesday, December 8, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

This article by Paul Levy is supposedly about Quantum Physics and the 2004 U.S. Election. Well, it doesn't actually say much about elections other than at the end, essentially that what actually happened depends on how you look at it. You know, Heisenberg's Uncertainty Theorem. And that the past really is created from the present by how we look at it, so it is somewhat meaningless to talk about what exactly it was. Actually I mostly agree. That is, I agree largely with the cosmology that he presents. He invokes various luminary quantum physicists like John Wheeler, the guy who came up with the idea of the black hole. This article by Paul Levy is supposedly about Quantum Physics and the 2004 U.S. Election. Well, it doesn't actually say much about elections other than at the end, essentially that what actually happened depends on how you look at it. You know, Heisenberg's Uncertainty Theorem. And that the past really is created from the present by how we look at it, so it is somewhat meaningless to talk about what exactly it was. Actually I mostly agree. That is, I agree largely with the cosmology that he presents. He invokes various luminary quantum physicists like John Wheeler, the guy who came up with the idea of the black hole. The quantum universe is one which pulsates in and out of the void multiple times every nano-second, endlessly recreating itself anew. Each moment brings with it a potentially new past, which we are the ‘builders’ of in the present moment. In this present moment right now there are endless possibilities, it is an infinitely textured moment in time seething with unmanifested potential. In the future, when we consider this multi-dimensional moment we are in now, we will probably focus our attention and only remember a certain slice or aspect of this very moment, solidifying it in time, and this will be our ‘memory’ of that seemingly past event. And yet, by the way we remember this present moment in the future will have an actual effect on the way that moment in the future manifests. So on the one hand, the way we contemplate the past has a creative effect on how the present moment manifests.

What Wheeler is pointing out through the delayed choice experiment, though, is that the past doesn’t actually exist in a solid and objective way that causes or determines our present moment experience like is imagined by classical physics. Rather, he is saying our situation is just the opposite. He is saying that by the way we observe in this present moment we actually reach back into time and create the past. It is not just the future that’s undetermined, but the past as well; just as there are ‘probable’ futures there are ‘probable’ pasts. Our present observations select one out of many possible quantum histories for the universe.

And I think he's right. But the trouble is that so many people, myself included, find the metaphors of quantum physics so inspiring and illuminating, without really having studied quantum physics. It seems to provide such a fabulous cosmology that backs up a new agey "we're creating the universe" view. And I guess it probably does. But it is mainly its metaphors that are inspiring, and it gets a little dangerous to actually invoke quantum physics for their support, when one doesn't really understand them. The trouble is that even though there are greatly respected theoretical physicists who advocate such a radical view of the universe, there are just as many, or more, scientists who consider it complete hogwash. Using quantum physics as a reference for these kinds of cosmologies, as applied to various aspects of every day life, just tends to make those guys really furious. Well, I think it is probably because they're wrong, and they're stuck in a fundamentalist materialist belief system that isn't going anywhere, and eventually our shared ideas about the world actually will catch up with quantum physics, as some of those guys die off, but it will take a while.

While looking around for references, I ran into the story about Alan Sokal, a physics professor who in 1996 carried out what he considered a hoax by getting an article submitted to a serious scientific journal, which he filled with what he considered unfounded nonsense like references to morphogenic fields a la Rupert Sheldrake, and applications of quantum physics to politics. And it created quite a scandal when he later revealed that he did it to see how easily one could fool people by referring to a lot of authorities and by saying post-modern stuff that people would like to hear, without any kind of scientific rigor. So he complained that he was able to get away with publishing an article that wasn't properly peer reviewed and that didn't argue properly for its points. Actually, the crux of the matter seems to be that Sokal believes in one finite objective reality, so therefore he consideres all other views unscientific, and he tried to prove that point by satirizing them. Much of what he was saying, and which he himself considered utterly ridiculous, had been said before by much more respected scientists than himself, like Bohr and Einstein and Wheeler. See here. Some of whom went a good deal further in relating theoretical physics concepts to sociology, psychology and politics.

Maybe the joke is that mutually exclusive views on the world can all be right, because you do essentially get back what you start off trying to prove. So fundamentalist materialist scientists can proceed to stack up more proof for the world being essentially newtonian and objective, and that all the weird stuff like relativity and quantum uncertainty and 12 dimensional space just applies to some remote circumstances and have nothing whatsoever to do with us, and it is all just a theory anyway. And, well, more free-thinking scientists might arrive at a very different world view where reality is fluid and greatly influenced by how we perceive it and think about it, and where wonderous things are possible. For the first group to consider themselves right, they have to consider the second group wrong, as there can only be one objective reality. Whereas the opposite isn't particularly the case. Anyway, I choose to bet on the models that explain the most possible phenomena in the world, rather than the models that have to suppress and ridicule all the stuff that just doesn't fit into them.

Anyway, back to Paul Levy's article. In a circular, non-linear and acausal feedback loop, the past effects us in this present moment, while at the same time, in this present moment we effect the past. The way we observe the past in this present moment actually effects the past which simultaneously effects us in this present moment in what I call a ‘synchronistic, cybernetic feedback loop.’ The doorway is the present moment, which is the point where our power to shape reality is to be found. In quantum physics the universe wasn’t created billions of years ago in the big bang but rather is being created right now by what Wheeler refers to as "genesis by observership." The mystery of this universe doesn’t lie at some point way back in the past, but rather, right now, in this very living present moment.

This quantum perspective on the past arising or being conjured up out of and into the present moment collapses the sense of sequential time and linear causality. This points to the non-local nature of space and time, in that the past, present, and future completely interpenetrate and are inseparable from each other. In a bit of quantum weirdness, if we ask whether the universe really existed before we started looking at it, the answer we get from the universe is that it /looks/ as if it existed before we started looking at it.

Quantum physics is describing what I call the physics of the dreamlike nature of reality. Like a mass shared dream, we are all literally moment by moment calling forth and collaboratively ‘dreaming up’ this very universe into materialization. And dreams, by their very nature don’t exist in a ‘flat-land’ where they are fixed in meaning, but are extremely multi-dimensional. When we contemplate the past in this very moment, it has the same ontological status of and no more reality than a dream we had last night. Just like this present moment, when we contemplate it tomorrow, will in that present moment have no more reality than a figment of our imagination.

Might or might not be science mumbo-jumbo, according to hardcore skeptics, but who cares. I like it, and I'd say it pretty much works like that.

Doesn't mean we can't discover who won the U.S. election, though. Or maybe it is just that I prefer that we discover one alternate past, rather than the other.

[ Knowledge | 2004-12-08 16:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, November 23, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Posted on William Gibson's blog, this is from an interview with Alvin Toffler, in "Modulations: A History of Electronic Music": Posted on William Gibson's blog, this is from an interview with Alvin Toffler, in "Modulations: A History of Electronic Music":"Today, the technologies of deception are developing more rapidly than the technologies of verification. Which means we can use a television camera, plus special effects, plus computers, etc. to falsify reality so perfectly that nobody can tell the difference. And the consequences of that eventually could be a society in which nobody believes, everybody knows that seeing is not believing, and nobody believes anything. With the exception of a small minority that decides to believe one thing fanatically. And that's a dangerous social/cultural situation.

One of the consequences of living through a period like this, which is in fact a revolutionary period, is that the entire structure of society and the processes of change become nonlinear. And nonlinearity I think is defined almost by the statement that 'small inputs can have large consequences.' While large inputs can sometimes have very small consequences. That also means in a political sense that very small groups can, under a given set of circumstances, achieve power. And that is a very threatening idea for anything remotely resembling what we believe to be democracy. So we're going into a period, I think, of high turbulence and considerable danger, along with enormous possibilities."

Hm, so should we let go and resign ourselves to not believing anything, as it is all just a virtual reality anyway? Or should we invent more advanced methods of verification? Truth and lie detection. Or maybe all of the above. Getting used to living in a fluid world where everything is virtual, but developing or maintaining a superior sense of what is REAL.

We do indeed run into that a lot of people still think there's only one reality, so they think they don't have a choice, and they can't fathom that people can manufacture realities for them. For a similar reason they've never learned how to distinguish truth from untruth. Because they've sofar mistaken well-crafted realities for truth.

[ Knowledge | 2004-11-23 22:04 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, October 19, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

An old piece from Deepak Chopra on What is the True Nature of Reality? An old piece from Deepak Chopra on What is the True Nature of Reality?One of the interesting things that science has found, this should have been obvious all along, is that what we call perception, what we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell, is really the least reliable test of what reality really is. We cannot trust our senses at all!

After all, the senses tell us that the earth is flat and we don't believe that anymore. The senses tell us that the ground that we stand on is stationary and we know it's spinning at dizzying speeds and hurtling through outer space at thousands of miles an hour. The senses tell us things have a certain taste, smell, size, texture. Maybe that's not the way they really are.

There was an experiment done at Harvard Medical School about 20 years ago. A group of scientists took some kittens and brought them up in a room that had only horizontal stripes. All the visual stimuli in the room were horizontal. Another group of kittens was brought up in a room that had only vertical stripes. And when these kittens grew up to be wise old cats, it turns out that one group of cats could see only a horizontal world. The other group of cats could see only a vertical world. And this had nothing to do with the belief system of these cats.

It's a phenomenon that psychologists call Premature Cognitive Commitment. Premature, because we make it at a very early stage of our development. Cognitive, because that's how they cognize or see the world. And commitment, because it fixes us to a particular reality, it imprisons us in a fixed mode of perception.

There are many variations of these experiments. In India, when they train elephants, they take the baby elephant and tie it with an iron chain to a huge tree. Then they start cutting the size of the chain and the tree. Ultimately you can tie the elephant which a big animal now, with a flimsy rope to a green plant but the elephant is unable to escape. It's made a commitment in its body-mind that it's in a prison!

Or you can do another simple experiment. Take some flies and put them in a jar. After a while remove the lid from the jar and you'll find that most of the flies, except for a couple of pioneers, will not be able to escape. They make a commitment in their body-mind that they're in a prison.

People will tell you who work in aquariums that you can separate fish from each other. They're in big glass tanks and the separations are transparent glass partitions. You can remove the glass partition after a while. The fish will swim to the edge of where the partition was and return . They made a commitment that that's as far as they can go.

All these experiments, and there are many variations of these, are pointing to a very crucial fact as far as the mechanics of perception is concerned. And that is that our initial sensory experiences and how we interpret them or how they are interpreted for us actually structure the very anatomy and physiology of our nervous system in such a way that ultimately the nervous system serves only one function: to keep reinforcing the initial interpretation. Anything that doesn't reinforce the initial interpretation doesn't even get into the nervous system. So if you don't have a concept or a notion or an idea that something exists, then your nervous system won't even take it in.

That's a very peculiar fact because it tells us that with bits of sensory experience, we'll never be able to comprehend the whole. We never will be! After all the human eye can see only between 380 and 500 billionths of a meter. There's nothing sacred between 360 and 370. It doesn't exist for us.

And so too for the other senses. This is true not only of the human species but of all species. A honeybee, for example, doesn't have the apparatus to see the usual wavelengths that you and I perceive. It senses ultra-violet. When a honeybee looks at a flower at a distance it doesn't see a flower. It sees honey from a distance but it misses the flower altogether. A snake would experience the same thing as infrared radiation which means nothing to you and me. A bat would experience that as the echo of ultra-sound which also means nothing to you and me. And a chameleon's eyeballs swivel on two different axis. You can't even remotely imagine what this would look like to a chameleon.

So what's the real nature of the world? What's it really like? We can't trust the senses. They give us a very distorted view. They break up that wholeness into a small fragment and we call it reality. We happen to agree about it. We even call it "objective reality" and we have a whole methodology that we call "science" to explore that . If you really understand what science is, then science at least until now has not been a method for exploring the truth. Science has been a method for exploring our current map of what we think the truth is. And the map is not the territory. The territory that we explore is really an extension of the map we have. If we don't have the complete map then we will not explore the territory that is not within the framework of that map. Maddening, eh? Not really. Limited maps are what drives us crazy, when we forget they're maps and they maybe no longer apply. The same as far as perceptions go. They all just access a little slice of a spectrum, and from then can even get stuck in a groove, leading us to adopt an even more limiting interpretation of what that is. The real real stuff is beyond the maps, obviously. Not that perceptions and maps aren't useful, of course. But its not the real thing.

[ Knowledge | 2004-10-19 23:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, September 29, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

That isn't really a very hard question, but it gets hard if one sort of starts in the wrong place. That isn't really a very hard question, but it gets hard if one sort of starts in the wrong place.

If you start off by assuming the universe and the life in it is just some random and meaningless occurrance, then it is a fairly meaningless question too. It just becomes something to say about people you really don't like. Or if your starting point is a story about God and the Devil, then it becomes a really convoluted thing to try to explain.

I start with the observation and assumption that everybody and everything fundamentally is good. Not particularly "good" in a good versus evil sense. Not a polarized idea. Rather, everything is inherently tending towards being and doing something that has a constructive angle to it. It is good for something in the bigger or smaller picture. Or at least it is neutral.

A rock is a certain piece of something that has certain properties. It doesn't do a whole lot, but it can be a piece of a mountain, or a wall, or many other useful things. If a rock once in a while falls on somebody's head and hurts them, it isn't because the rock is evil and was trying to do some damage. It is rather passively just being a rock, and obeying the law of gravity and things like that. Obviously.

A tree is an alive entity that does a whole lot more, and actively extracts stuff from the environment, grows certain structures, and reproduces, etc. It has a certain natural cycle of how it does things. If one day a dead branch falls off a tree and kills somebody, it isn't because the tree is evil and meant to do that to be mean. Dead branches fall off eventually, and it was just time, and the wind helped a bit and then a bird sat on it. None of which was meant to harm anybody.

How about animals, then. They spend a good deal of their time going around killing other living entities. At least they eat plants, killing them in the process. Or they hunt down other animals, kill them and eat them? Is that evil? Well, we might not like it when we look at it, but the animals appear to have no ill will about it. That is just what they do, and they need to eat. Even the animals eaten don't seem to be as stressed about it as we humans might be when contemplating it. A fish eats another fish. They second fish would instinctively get away if it could, but if it gets eaten there doesn't seem to be much involved that we'll recognize as emotion or suffering. Nothing evil anywhere. Even if they sometimes do it for sport. Our cat will happily keep a wounded lizard alive for as long as possible, while lazily dashing it around. Or bring a half-dead bird into the house and drag it around. Is it evil? Well, we sure don't like it, but no amount of yelling about it seems to make any difference. It will happily do it again. Because it serves a function. A cat in the wild would of course need to practice its hunting skills in order to get food and survive. Nothing personal about it. It is not that it doesn't like birds or anything.

So, now, us humans are a little more complicated. We think abstractly and have feelings about complicated things. But most of the time we also just go about our business. We learn how to do things, find a spot to do it in, we eat, reproduce, entertain ourselves, form social groups, build tools, etc.

Everybody's inherently just trying to live and do what seems to be there to do. When provided with a choice, we'll generally choose the better one according to our aggregated instincts for what we're trying to do and what works. Life is trying to survive well and do better. It would be fair to assume that such a fundamntal aim is built into all life-forms. Certainly we can observe it in anything that lives.

But we humans are more vulnerable to bad information. In part because we do many things abstractly, apparently as opposed to many other players in nature. And, related to that, that our activities get very complicated. It is no longer just to eat the first thing that comes along that looks edible whenever we're hungry. The choices concerning maintaining and improving our lives are increasingly made with abstract information, and with the real stuff being quite removed from us. And we're tied into abstract social systems that might be beyond us individually to understand.

So, if I'm a soldier trained to kill people, and I do so, is that evil? Not necessarily. I might have the information that I'm doing so in order to protect the large social group that I consider myself belonging to. I might have been brought up and educated and trained to look at it a certain way, and I simply do what I consider my duty, and what seems logical. Not necessarily anything personal against the people I kill. I'm acting according to the information I have, the training I've been given, and the circumstances I'm in.

If I were a German soldier controlled by the Nazis, does that suddenly make it different? Not really. I'm still a victim of the information I have and what I've been trained into, and I might have limited choices available to make it all different.

What if I'm a burglar or bank robber, stealing with a gun in my hand, to fund my crack habit. Evil? Maybe just the only solution I saw available to me. Again, doesn't make it right or permissible in society, but for the individual it might still be a matter of doing the best I can with my limited options, and possibly false information and misguided beliefs.

Am I saying that there's no evil, and everybody's just acting within the information they have? Not quite. That's what's going on most of the time. But there's still something we could call "evil". Which is relatively rare.

You know, when one looks at what is going on in the world, and one doesn't get around to seeing it in such an "understanding" fashion as I attempt here, one might well reach some different conclusions. There are bad people in the world, and they seem to get away with it. Being bad works. It is much easier and more productive to think about just yourself, and not care about anybody else.

It is a misunderstanding, really. Again, based on faulty information, an individual looks around him and concludes that other people are evil and therefore they have the upper hand. And insted of continuing to be the victim of them, he flips around and instead assumes what he believes is their kind of personality. Bad. Evil. Thinking just about yourself, and not caring who gets hurt when they get in your way.

It is not about certain types of actions that are inherently evil. Those depend on the context. What is key here is the intention. Somebody who actually intends to do harm and it doesn't bother them.

It is a fake personality. Nobody really were like that originally. There are no evil babies. But a sufficient amount of torture and abuse from an early age from one's parents or from authorities or from what one perceives as "the system" can do it to the best of people. Or one might simply take a "logical" overview of the world and mistakenly conclude that being evil is the way to go.

One might do all that unconsciously, without thinking it through, simply changing one's personality to survive. Or, more chillingly, one might consciously conclude that it will work and one will get ahead over others by being that way.

Very few people have adopted what we could call an "evil" personality. Maybe a couple of percent of us. But that can create a lot of havoc. And any of us might in some moments, for reasons we might not completely understand ourselves, instinctively choose to be evil, and to act with the sole intention to hurt others, maybe to bring oneself ahead.

Either way, it is a copy of what we think others are doing. Which they probably weren't really doing for the reasons we think. The parent who was mean to you when you were little might have had their own story of being a victim of the circumstances and of bad information. They might think the Bible told them to beat you, to make you a better person. Or they were repeating what their parents did to them. Or they were lost and stuck and unaware.

But one way or another, some people end up acting as if they're evil, and they will deliberately hurt other people and enjoy it. Psychopaths. That only happens when they're already pretty bad off, when they've closed their hearts, when they never developed any empathy for others, and when they're loaded with false information about how life works. But there's plenty of that around, and no general education that teaches you how to be social.

So, what to do about that? Well, with the majority of people, who're mostly trying to do what they think is good, reason and kindness and good information will work. If they do something that hurts others, one can make them understand that, and they would naturally feel bad about it and try to do it better. But with the smaller number of people who're stuck in the evil personality, it is quite different. Being nice to them is not going to help, and will only show them how weak you are; and showing them how their actions hurt others is only going to encourage them. Because they aren't really there, but they have adopted a strategy quite opposite to yours or mine, and they've invested a lot in cementing it into place.

Anybody might change. One might wake up and realize what one is doing, and change one's ways. But with this kind of thing, it doesn't happen easily or casually. It does happen, though.

But in the meantime it would be valuable to develop a keen ability to notice who's who. If the person in front of you is still connected with their basic goodness, then you can talk with them, give them information, tell them truth, share how you feel, and you might get along better, and they'll use what they learn to make better decisions afterwards, more beneficial decisions. If the person in front of you is one of the very few who have lost touch with who they really are, and adopted an evil personality, then it is all different. They'd use everything they learn about you to gain an upper hand over you and get you out of the way.

Now, many people have bad inter-personal skills and foggy perceptions and lots of emotional baggage and might easily conclude that what I described fits perfectly on their ex-wife or their boss. So let me say again that the odds are that it isn't so. Most likely any differences could be sorted out if the emotional baggage gets out of the way, and it becomes evident that all parties really would like things to work.

It is a bit dangerous to even have labels like that, as people who can't figure out how to understand each other and get along are likely to hide behind horrible labels they apply to each other. You know, if you have a different belief system than I, and you do things I don't like, you're just evil. No, it is not that I'm talking about.

No, we're more talking about serial killers and otherwise criminally insane psychopaths. Oh, and some of the people who are gang members, muggers, terrorists, etc. But far from all. And indeed there would be people in the group that wouldn't be very obvious at all. Well-educated CEOs of companies, government officials, people who on the surface appear to have great people skills, be charming and eloquent, have families, etc. But underneath, their modus operendi is to sabotage and disable everybody else, preferably in the hidden, so that they can get their own way and the others don't. Everything looks right on the outside, to the casual observer, but inside we have the walking dead, and they leave a trail of destruction in their wake, which they well might succeed to make appear as somebody else's fault. Hard to pinpoint, but very important, to spot the psychopaths that don't look the part. And not to pick them as your leaders.

As some point we might with some luck have a society that makes it easier for us to connect with our basic humanity, and which no longer rewards psychopathic behavior. Until then it is just very necessary to pay close attention to what people's basic motivations really are.

Another angle on it is that despite our individually fairly noble intentions, we might very well accidentally create organizations that possess similar characteristics as that of a psychotic individual. It is not very hard for a large corporation to be evil, and to act in its own interest to the detriment of anybody who gets in the way. For that matter, it is inherent in its design. Only if some of the people running it go way out of their way to make it act more decently and socially can it be otherwise.

[ Knowledge | 2004-09-29 19:28 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, September 24, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Have you stopped beating your wife? We all know that kind of trick question. If you accept the question at all, whatever you answer, you've admitted to something you didn't want to admit to. Doesn't have to be a question either.Today the captain is sober Which, however correct it might be, of course squarely plants in one's mind the idea that there probably are plenty of days when he isn't sober. Whether that is true or not, it is now stuck in our minds. The magic of framing.

Now, Seb Paquet mentioned an article, Cognitive Symmetry-Breaking by Nicholas Williams. It talks about the paradoxical thing that happens the moment we overlay any kind of model on a system. You know, any kind of labels or categories or ordering. The surprising thing is that we start losing information the moment we describe things and try to slot it into a certain expected pattern. Well, it shouldn't really be surprising, but it is somewhat counter-intuitive to the person on the street. Or to most academics, for that matter. It seems like we're wiser when we can describe a system and say what it IS. And, yes, there's a lot to say for the practicality of being able to label things, but the truth of the matter is that we inevitably are losing information by applying any kind of model to a system.

Reality, before it is described and ordered, is infinite. Everything is possible, but nothing is finite yet. As the author describes it, there's symmetry there, because nothing is determined. Everything about the system is what is is, and is equally right.

But we humans are not very comfortable with something that is infinite and undescribable. It is chaos, it is confusing and seems meaningless. So we tend to break the symmetry by describing it, and by starting to be discriminating, and pick out certain pieces of reality as being more important or interesting or known than others. And we think that the system is now more understood and ordered. Really, the system didn't change. We just (over-)simplified it in some abstract way that we could manage to fit into our limited mind. And we left out a helluva lot of information. We practiced cognitive symmetry-breaking.

Cognitive symmetry-breaking allows us to feel right about a whole bunch of things. And it also starts trapping us in all sorts of faulty thinking patterns. Black and white thinking. We start thinking the map is the territory. We start beliving our limited models to be more real than reality itself. Because we have a lot of trouble facing the real thing, so it is easier to pretend it doesn't exist.

At this point in our evolution, we can't really live without labeling things, and categorizing things, and being discriminating about what we do and what we don't do. We couldn't talk with each other if we didn't. We couldn't convey knowledge. We couldn't stay alive if we didn't know what to eat and what to do. And it seems to be our innate ability to use abstract thinking to do these things. Abstract thinking, which we think is really cool and advanced, but which really amounts to reducing an infinite universe to a cartoon format we can understand.

Nothing terribly wrong with that. It seems to be in part what we're here to do. But there's a balance to find there. Specifically, thinks start going wrong when we forget the simple fact that we're abstracting (simplifying, representing as symbols) a vast and mysterious universe into something that is at best a vaguely workable model. And when we forget that, we open the door to just about any mental illness or cognitive fallacy there is. Fundamentalism and our tendency towards hurting and killing each other for stupid abstract reasons - it all comes from the same error.

Now, because we have gotten into the habit of thinking of things that can be described as real, we're often easy prey for the type of manipulation by framing I started by mentioning. We very easily grab on to the implicit frame we're presented with, just because it seems more comfortable than the great unknown of "everything else". So if you look at CNN's website, and they present you with a multiple-choice poll like:

a. Are you satisfied with the progress of the war in Iraq?

b. Should we send more troups?

a lot of people are not going to notice that there's no place to indicate your preference for any of all the other possibilities, or for rejecting the choice, and that you get trapped in a certain mindset without necessarily noticing.

OK, so the awareness of basic things like that really ought to be something we learn in kindergarten. But the opposite is what is taking place. We get cemented into certain fixed models and perceptions, more and more thoroughly.

It can be reversed of course, but not easily. Going from comfy certainty of abstract banalities towards the scarey uncertainty of the universe as it is - that's in many ways difficult and counter-intuitive. And there's no help to get from some easy system that takes you through the steps.

It is not for nothing that the state of Enlightenment often is described exactly as the result of letting go of all these little mental and emotional falsehoods and needless categorizations we're holding on to. You know, going back to allowing the universe to be what it is, without having to have any preference as regards to what happens. Simply being keenly present with what is.

Well, there's a balance somewhere, I'm sure. Where we can harness all the advantages of abstract thinking, without getting lost in any of the insanities of its misuse. Starts with a continual awareness, I think. Of the difference between the universe and a picture in our head.

[ Knowledge | 2004-09-24 23:01 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, September 6, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

I kind of like taking personality tests. Probably because I'm searching for a more clear and simple idea of who and what I am. Most of them probably helped a bit and came up with something I could agree with. Didn't make much pervasive difference though. They're mostly too simple, or telling me things I already know. Dividing all of humanity up into 4 or 8 or 16 types might have use, and might help us notice our differences, and be able to communicate better once we're aware of them. But they don't really tell us who we are. I kind of like taking personality tests. Probably because I'm searching for a more clear and simple idea of who and what I am. Most of them probably helped a bit and came up with something I could agree with. Didn't make much pervasive difference though. They're mostly too simple, or telling me things I already know. Dividing all of humanity up into 4 or 8 or 16 types might have use, and might help us notice our differences, and be able to communicate better once we're aware of them. But they don't really tell us who we are.

And most of the well-known tests are somebody's copyrighted, heavily guarded intellectual property and business. I.e. some psychologist invented it, put his name on it, and charges 100 bucks for letting you answer a bunch of multiple choice questions and getting the canned answer. That should raise a bunch of red flags right there. Trying to own a personality assessment, and trying to stop other people from using it, is kind of a strange thing. Even if they're good. Here's an article describing different tests. Hey, maybe I should make my own test. The Funch Holographic Mind Spectrum Instrument. $500. And if you don't pay, you just don't have a type, hahah.

I think I prefer more open, but complex and difficult systems. A good astrologer can talk to me for hours about myself, revealing lots of insights I wouldn't think anybody could know. Or there are systems that simply outline many different kinds of programs people might be running, and ways of dealing with them. Like, NLP has Meta Programs. For example, one might have a preference for moving towards desirable things or for moving away from undesirable things. Or one might be internally focused versus externally focused. One might insist on making one's own decisions or one might require the guidance of others. One might have a preference for looking for options and possibilities versus looking for what must be done and what the procedure is. One might sort the world by differences versus sorting it by similarities. One might be active or passive. Etc. And one might use different of these programs in different situations, or one might use them in a certain sequence. For example, I have to work through different possibilities before I can arrive at what needs to be done. I want input from others, but I ultimately want to make my own decision. Other people do it in the opposite order. Anyway, those are more tools than they're personality types, even if some people might keep a certain constellation of them through their life.

Anyway, what I wanted to mention was the idea of Jung's that one gets to be in trouble if one isn't living according to one's type. I.e. if one tries to be somebody else than one really is, and thereby one "falsifies" one's personality type, by presenting a different one than what really comes natural. It is implied that we'd have one personality type which would be stable and unchangable through our life, and that our life would be most happy and smooth if we stay true to it. And if we try to live another type, our life will be stressful and ineffecient.

Now, again, I'm not sure I believe we really ARE one of 16 or so types. But there's something to the idea of staying true to who we really are. We might experience being in the flow if we're in harmony with our own nature, and we might experience hardship and stress if we don't.

Here's a brief overview history of Jung's personality types and the idea of falsifying type.

A number of well-known tests are based on Jung's categories, but leave out any assessment on whether one is just pretending to be that or not. The Myers-Briggs test, or rather the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, which is more comprehensive, helps people find out whether they're predominantly an (I)ntrovert or an (E)xtravert, whether one is (S)ensing or i(N)tuiting, (T)hinking or (F)eeling, (J)udging or (P)erceiving. One ends up with a four-letter type, one of 16 different constellations. When I take it, I'm usually split on Introvert and Extravert, or it might go either way depending on what mood I'm in. But let's say I'm ENTP. That is the Inventor type. Those are non-conformists who are probing for new possibilities, and who pragmatically work on implementing new solutions. Now, looking over the types, there isn't any other one that would suit me better. So I might not have fooled myself in terms of my answers. I'd know nothing better than sitting around exploring interesting possibilities and inventing new things all day. And I guess I do that part of the time, and that's great. But the more stressful parts of my life might be when I do everything else. Which I might not have to if I had been really successful in what I'm good at. I.e. if I actually had invented something and gotten it out to the world, I'd probably be deriving an income from it, and I could get quite some milage out of it. So, instead, I've spent a significant portion of my life trying to do work for other people, conforming to their needs, and sort of muddled through, trying to keep up with paying rent and taxes and things like that.

The point is not necessarily the typing system. But what if I somehow, by any means, learn enough about myself and how I work. And I actually respect it and live my life accordingly. If I'm good at starting things, but not at continuing them, well, then I should be starting things, and get other people to continue them. If I thrive on exploring different subjects and talking about it, then I should arrange my life so I do that. Doesn't matter what exactly our modus operendi is. What matters is that we do what works for us. Seems so obvious, but we so easily miss it.

The trouble is of course that we usually need some of that which we aren't good at. For example, most of us need to either structure that which we're good at as a viable business, or we need a job that allows us to do it. And if the business-making part is not one of those things that realy flows for you, you'll need somebody else to help you with that. Or you might be really frustrated if you try to force yourself to do those things that are needed, even though it isn't you.

In an ideal world we'd all be doing exactly that which we're excited about and really good at. That which really flows for us. And we'd be free to do mainly that. And we'd discover to our delight that those things we're good at dovetail really nicely with what some other people are really good at, so we can complement each other, and form teams.

Maybe it already is an ideal world, and we just haven't noticed. So we go around trying to pretend to be something we aren't, trying to do things we'll never be good at, when we really ought to let somebody else do those things. And when other people really could use that I started doing my particular part a little more directly, rather than futzing around.

I'm looking for the magical button. Something that makes me and others just snap into their true self, acting accordingly. A test or divination or process might give hope that it will make it happen easily. I suddenly have an epiphany and realize what I'm really like, so clearly that I start living my life that way. And everything then is flow and synchronicity and I effortlessly make great things happen, now that I realized what it was I was supposed to be doing. I wish it were that easy. No test or workshop has done that for me so far. It might take real work. Probably on an ongoing basis. But one never knows. Life might surprisingly turn out to be easy, if one just runs into the missing piece. And the missing piece might be you.

[ Knowledge | 2004-09-06 23:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, August 6, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Jon Udell quoting Alan Durning:Play back the last 10,000 years sped up, so that a millenium passes by every minute. For more than seven minutes, the screen displays what looks like a still photograph -- the blue planet Earth, its lands swathed in a mantle of trees. After seven and a half minutes, there's a tiny clearing of forest around Athens. This is the flowering of classical Greece. Little else changes. At nine minutes -- 1,000 years ago -- the forest gets thinner in parts of Europe, Central America, China and India. Twelve seconds from the end, two centuries ago, the thinning spreads a little farther in Europe and China. Six seconds from the end, eastern North America is deforested. This is the Industrial Revolution. And of course, in the last 3 seconds things get to look really alarming.

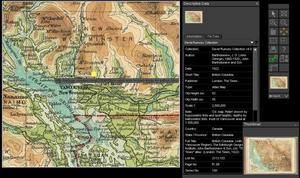

Anyway, Jon talks about David Rumsey, a philanthropist who collects historical maps, scans them at high resolution, and makes them freely viewable on the Internet. He gave a speech at an open source conference. He says: Anyway, Jon talks about David Rumsey, a philanthropist who collects historical maps, scans them at high resolution, and makes them freely viewable on the Internet. He gave a speech at an open source conference. He says:I thought about donating it to a university, but their libraries focus on preservation, they'd have put my collection in a vault and there would have been no access. Along comes the Internet, and I found we could do even more with the digital content than with the originals. We serve over 7000 visitors a day. A typical map library will serve 200 visitors a year. Historical maps, who cares about that? Well, he's apparently put a lot of work into providing some very impressive high tech tools for exploring them. One can sequence maps for different time periods, to see how things change. One can overlay maps on each each other, including overlaying old maps on modern 3D elevation maps, and you can then take a virtual flythru through an old map.

Maps are a good thing when they help us see the world and our history more clearly. Which they do much better in online interactive form than as paper in the basement of a university.

[ Knowledge | 2004-08-06 09:42 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, August 2, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

"dewf" mentions in a comment a concept I've often thought about. "dewf" mentions in a comment a concept I've often thought about. I've always wanted to see websites which have a hierachical introduction to topics. This is done to some extent now with hyperlinks, but generally you get a table of contents and then the details. Books try to do this to some extent, but a lot of times, they are more linear than hierarchical. Funny that we learn mathematics and chemistry and such from the bottom-up, instead of top-down.

What I'm thinking is that a how-to or informative book should start with one paragraph which tries to explain the whole gist, then maybe a 1 page explanation of the very same thing, then a 10 page explanation. Personally, I much prefer to learn that way. Give me a paragraph first that gives the core ideas. Then I know the key importances, and I'll have a mental framework that further details can fit into. But it is usually not how learning materials are presented. So often you have to wade through hundreds of pages before you get the simplicity, if you even ever find it. And so often you'll just keep it to yourself, once you've found it, as a reward for working hard at discovering it.

Several times I've had to install a payment gateway between a shopping cart program and a credit card processor. The first one was CyberCash. They gave you 20MB of information to explain how to do it. Many hundreds of pages, in dozens of files. Most people said at the time that it on the average took a month to install it. But, really, what I ended up with after digesting it was 5 lines of PHP code that did the trick. It was really very simple, and I could have done it in 5 minutes, but the simplicity was a secret, so it took a lot of work.

The way you sometimes get it is by running into somebody who's a master in a certain subject, and after dinner, when you'e built up a bit of trust between you, he might casually share one of the core simplicities of his subject. Something that suddenly makes it simple, rather than complicated, for you. Something that would have made all the difference if you had known it earlier.

Not just any simple one-paragraph piece of information will do. The key is that it needs to be action oriented. It needs to enable you to do something. Actually enable you as much as possible with the smallest piece of information possible. Maximum knowledge exchange in the smallest unit.

Let's say I wanted to learn to speak Esperanto. Random House's dictionary will give me a good one-paragraph definition of what it is: an artificial language invented in 1887 for international use, based on word roots common to the major European languages. Well, that's good. Tells me what it is. If somebody mentions it, I know that it isn't a fruit or anything, and I can pretend I know about it. But it tells me zero about how to actually do it. OK, in this case it is unusually simple, so there actually are people who've provided what I'm asking for. The sixteen simple rules of Esperanto. There it is in one page. If we put it in one paragraph, it might be:

Nouns all end in -o in singular and -oj for plural. Add an -n if it is the object. La is the definite article. Adjectives end in -a, adverbs in -e. Personal pronouns: mi, vi, li, ŝi, ĝi, si, ni, vi, ili, oni, meaning, I, you, he, she, it, oneself, we, you, they, they/one/people. Verbs have these endings: -as; past time, -is; future time, -os; conditional mood, -us; command mood, -u; infinitive mood, -i. Use the word ne to make things negative. You can put the words in the order that suits you. Everything is pronounced at written. Accent always on second-to-last syllable. And that's about it. You'd need some vocabulary, obviously, but there's the majority of the grammar rules.

OK, French would be harder. But I'd kind of like to start with some kind of inventory. Like:There are 9 different types of words: nom, déterminant, adfectif qualicatif, verbe, pronom, préposition, adverbe, conjonction de coordination, interjection. Verbs are conjugated in 3 main groups, for infinitives ending in -er, -ir, -re. There are 6 different modes of verbes: indicatif, subjonctif, imperatif, conditionnel, infinitif, participe. 19 different tenses. The language has 18 consonant sounds, 16 vowel sounds, and 3 semi-vowels. OK, takes work, and doesn't really enable you to do it, but it gives some kind of framework. Some expert could do a good job there. But I'd be hard pressed to find this kind of overview anywhere. Like one paragraph overviews of all languages.

Simple how-to information would be useful in any field, of course. But there are various fields where it maybe is more readily available, or where the need for it is more recognized. A Survival Manual is obvious. You go into the wilderness, and you can manage carrying one book that might tell you how to get out of various situations you'll run into. How to find water, how to navigate, how to know which mushrooms you can eat.

Obviously in home improvement. There will be books with nice color diagrams and step-by-step instructions for how to do your own plumbing or how to put up drywalls.

Look at this site, that I incidentally did the database for: Bagelhole, collecting low-tech sustainability how-to's.

Now, then, what would be involved in making a platform for gathering how-to's from any field, organized from simple and short towards gradually longer and more detailed versions? Kind of like wikipedia, except for the multiple levels, and the focus on enabling action-oriented how-to information.

Simple enough to make a site organized like that. But would it sort itself out simply by being a wiki that people could edit? Or does it take something more complex to be able to select the best simplicities?

A problem is of course that not everybody will agree on what the one-paragraph version should be. So maybe alternatives need to compete and be rated. Maybe there needs to be different versions depending on what one is really trying to do with the subject.

Mainly it all needs to be available in a unified structure.

How does one make metal? How does one find water? I'm sure the information is on the web. But where's the one-paragraph summary?

When people's cars break down while driving, most of them get out and open the hood and poke around. What do they actually do, and what is the best practice for actually fixing something? I don't know, I'm a software guy. I'd like the one-paragraph or one-page version, please.

If it were a book, I'd want the book that tells me briefly how to do just about anything. It is probably better suited to be a website, as I'd want to drill down into further detail if the first paragraph doesn't do it for you. But I'd like those first paragraphs to be good enough that it would be meaningful to carry them all around with me. Or to look them up via my cellphone.

[ Knowledge | 2004-08-02 09:50 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, July 27, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

From Seb Paquet: From Seb Paquet: Kevin Kelly asks:"What are the best how-to books, videos, software, websites that you've ever seen? I don't care what the topic is, I am primarily interested in the execution." Building a distributed body of how-tos would be another great application of structured blogging. Paging Marc Canter: must add Open How-Tos to your list of digital lifestyle standards.

Update: Jeremy picks up the digital lifestyle aggregator idea:"Now imagine that profile as a sort of e-portfolio, containing most of the stuff you careed about, things you were thinking about, connecting you to everyone else who wanted to learn the same things, helping you find the information and resources that would help you learn... " Yes, yes, yes. Of course we need all of that. A comprehensive open archive of the how-tos for ... most everything. And an easy way of finding everybody who want to do the same things. And we might actually get to work.

[ Knowledge | 2004-07-27 20:27 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, July 20, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Anthony Judge mentioned his article The Isdom of the Wisdom Society. Anthony is one of the smartest people I know of, and his enormous site and his articles are somewhat intimidating to approach. Certainly clear enough to read, but he covers so much ground that it takes your breath away a bit. Anthony Judge mentioned his article The Isdom of the Wisdom Society. Anthony is one of the smartest people I know of, and his enormous site and his articles are somewhat intimidating to approach. Certainly clear enough to read, but he covers so much ground that it takes your breath away a bit.

This piece was for the UN World Summit on the Information Society, and is exploring information and knowledge and wisdom, and then points to what's maybe at the core - what IS and how to BE with it. Many studies explore the importance of the distinctions in the sequence from "data", through "information", then on to "knowledge", and finally to "wisdom" [more]. At each stage there is a much-studied challenge of "management" (as in "information management" and "knowledge management"). Arguments are also made for the importance of a corresponding "information society" or of a "knowledge society" -- perhaps expressed as a "knowledge-based society". But clearly it is easiest to argue the case for an "information" focus, especially to hardware, software and information vendors -- hence the title of the UN World Summit on the Information Society. It is more challenging to make a case for a "knowledge society", especially since "knowledge management" is in process of being disparaged as a fad term lacking any real content -- notably in those corporate environments that claim to practice it. And yet it is precisely the transfer of knowledge, in the form of "know-how" that has been a preoccupation of the United Nations over many development decades. But knowledge is a troublesome thing to get a handle on. If I know one thing, and you know another, and a lot of knowledge is hidden in the library or on the net - what do we really know? Is it knowledge if we put it all in the same database? We so easily end up scattering both our information and our knowledge about, and apart from ourselves. Maybe splitting something apart that really isn't apart. Like ourselves.

What we usually really need is the wisdom. To somehow transcend keeping track of the information and the knowledge, and somehow have the instinct for making good decisions, even in difficult circumstances. The distinctions between data, information and knowledge are increasingly problematic as is to be seen in efforts to give content to "knowledge management". It is perhaps helpful to see the sequence as a progression from more objective to more subjective -- namely an increasing dependence on judgement, cognitive ability, experience and the capacity for synthesis (see Evaluating Synthesis Initiatives and their Sustaining Dialogues, 2000). Whilst software can be provided to manage information, those packages designed in support of "knowledge management" are far more dependent on the knowledgability of the user. Similarly, whilst data and information can be readily explained, this becomes more of a challenge in the case of knowledge. This is exemplified in the case of appropriately ordered information on a food recipe. Although the recipe may be followed, it is only in the light of the knowledge acquired through past learning and experience that there is any guarantee that the result will be tasty. OK, we need to understand wisdom better. Wisdom involves subjectivity, and it isn't easy to just break it down and explain it. It can't easily be transferred.

Wisdom seems more intimately bound to space-time than information and knowledge. But in a way that makes it sort of timeless. It has more to do with the quality of how you know and how you go about things than with the actual content. It involves a quality of discernment largely absent from conventional knowing. So, maybe that all leads us towards the mysterious quality of being present, of the "Now", of what IS, and how we act in it.Paradoxically, as one might expect with respect to a "timeless" quality, its uniqueness derives from a way of "being in the present". This focus on the present is echoed in many sources of wisdom -- as the key to appropriate action in the more extended framework of space and time. Its proximity is for example stressed in various religions. Judaism and Islam recognize that the separation between Heaven and Hell is but a "hair's breadth" -- echoed by Zen in the acknowledgement that the separation between enlightenment and ignorance is again just one "hair's breadth".

It is for this reason that -- playfully -- it is suggested here that the domain of wisdom might usefully be recognized as "Isdom". This might be seen as corresponding to terms such as "Kingdom", "Dukedom" or "Fiefdom" -- except that the focus is on the domain of "is-ness" in the present. Well, that's very refreshing. The Zen of the moment. Again, hard to take apart, by its very nature, but it can be hinted at, maybe a bit poetically.As the domain of the present moment -- the present instant -- Isdom is a place of being characterized by a quality of appreciating that moment, and sustaining that appreciation. It might be understood as the mode of expression and interaction in the instants before conventional exchanges occur. As such it resembles a kind of existential foreplay -- in part made of glances and understandings that are global in their quality -- an interplay of being. For example, one international event focused on The Butterfly Effect as the "coordinates of the moment before discovery". It is the sparkle on a pool -- or in a person's eyes (or those of any other animal).

The moment may be imbued with a sense of incipient knowing or of intuitive re-membering -- of re-cognition. It may be understood through the anticipatory quality of "happening" -- a sense of in potentia -- as when encountering a significant other (perhaps for the first time). It is, for example, the instant before any process of falling in love -- "at first sight" -- namely before intentionality or action of any conventional kind. Well, I'm not going to go on and quote the whole thing, but Anthony goes on to explore how we might possibly "contain" the is-ness. It so easily gets spoiled and reverted into banal normalcy. So hard to hold on to. It is like the plasma needed to create nuclear fusion. The hardest part is to keep it together without it being messed up by the stuff that isn't it. How can the present be reified - made more real? How can we recognize and tap into FLOW? We might have to look for answers in quite different places than what we normally use to take things apart and analyze them. Indeed the addictive "normality" of our habitual world is exactly what keeps us from understanding the zen of the present moment, from tapping directly into the consciousness of wisdom and becoming more fully alive. The things we need to *get* easily border on craziness when seen through the eyes of our collective normalcy. The things we can neatly describe and categorize are not it. From the Tao Te Ching: The Tao that can be described is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be spoken is not the eternal Name.

The nameless is the boundary of Heaven and Earth.

The named is the mother of creation. To really BE in the present moment, and to be in touch with our inherent wisdom, we need to get beyond most of what we can think of putting a name to. Yet, the world is made of the stuff that is observed and named. Ah, delightful paradoxes.

[ Knowledge | 2004-07-20 14:55 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, July 18, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

I occasionally wake up sweating, thinking I've forgotten to do my paper route, and undelivered newspapers are stacking up somewhere. When awake, the feeling gets replaced with a vague feeling that there's something somewhere that I've forgotten, and it is important. Of course I haven't had a paper route for, oh, close to 30 years, so it probably isn't that. Except for that I'm not totally sure if I handed in my resignation, so maybe there really is 20 tons of bundles of old newspapers standing there, and a lot of angry customers waiting for their morning paper. How do I know? I occasionally wake up sweating, thinking I've forgotten to do my paper route, and undelivered newspapers are stacking up somewhere. When awake, the feeling gets replaced with a vague feeling that there's something somewhere that I've forgotten, and it is important. Of course I haven't had a paper route for, oh, close to 30 years, so it probably isn't that. Except for that I'm not totally sure if I handed in my resignation, so maybe there really is 20 tons of bundles of old newspapers standing there, and a lot of angry customers waiting for their morning paper. How do I know?

But the feeling is quite close to how I relate to many kinds of information. You know, there's something I should know about, and that I should be doing something about, but currently it is disconnected from what I actually do, and I don't quite remember. But it might come back and bite me at any moment, at which time the *information* will clearly show that I'm an idiot who's not doing what I'm supposed to. Until then, the information might well be hiding somewhere where I'm not looking. So, where should I look to find all the information I should be aware of?

Paying bills is a bit like that for me. Relations with public authorities certainly is. I have the sneaking suspicion there's probably some big things I should be doing that I'm not, like paying taxes or having the proper licences, permits and immigration papers. I have some vague ideas. But, I look around me, and there's nothing in my environment that tells me much about any of those things. It takes some hard work to go and track down the information I'm supposed to have, and then figuring out what to do with it. And I never know if I got the whole picture. Yet, there's no excuse for not knowing the law. Meaning, there are 10s of thousands of pieces of information I really should know about, many of which could put me in jail if I didn't act correctly in accordance with them. Oh, most other people don't know them either, but they somehow manage to get the most vital pieces, and then they look around themselves and see what other people do, and they figure they can't go all wrong if they do roughly the same.

My point is that information is typically something disconnected and abstract. Data certainly is. It is some kind of extract representation of something, which possibly might be real. Information is when we put some of that data together so it seems to say something coherent.

I get a bill in the mail. That's a datum, or maybe several. If I study it and discover that, aha, I'm supposed to pay this before the 10th of next month, and this is the amount, then that is information. At that point it is still unconnected to everything else. Who says I'll remember that next month, or that I have any money at that time? Where do I put this thing so I find it again? Well, if I really think it is terribly important, I make some kind of system to remind me. I make a folder for that creditor, I write it in the calendar, I try to estimate my budget over the next month. Of course, you say, everybody does that. But it is not that *of course*. It is just that you're used to living in an information world where things like bills and deadlines appear to be real. Even though they're disjoined and often inconsistent abstractions, several levels removed from anything real.

If you call up Microsoft for tech support, based on some odd problem you have with Windows, they'll usually end up telling you that the answer is there, plain and clear, in technical note number 17536, and you're a bit of an idiot because you didn't know that. They have their information asses covered, just like the law. It is your fault you don't know.

To be fair, most open source mailing lists work like that too. You ask a question, and there will always be somebody quite willing to tell you how stupid you are because there's some file somewhere that has the answer on line 514. And you didn't know. It is a bit of crime to not have processed and tabulated all the information in the world.

In a society like the french, often things aren't said explicitly, but it is assumed that you'll somehow know. The school doesn't necessarily give you a piece of paper that says when vacation is over, because it is assumed that everybody knows. If you apply for being admitted into a new school, they might not even bother to tell you if it was accepted or not, because you somehow ought to figure that out by yourself. The business world works like that too in many ways. You're sort of supposed to guess what is going on, even though the information isn't readily available, and your boss isn't talking. You've gotta be well networked, drawing on an extensive intelligence network when you do anything. You're supposed to know things, but there might not be anybody who tells you exactly how. And the available data itself might not help much.

There's an implicitly idea somewhere that data adds up to information. Which potentially might be structured into knowledge. And if you then really internalize it, it might become wisdom.

It is a questionable model. It assumes that the direction is from disjoined snippets of data towards something more integrated and useful. Who says it works like that? Nature doesn't seem to me to work like that. There nothing quite equivalent to data out there. Nature includes lots of systems that have partipating elements that send messages to each other. A plant or animal that is trying to procreate often sends out millions of little seeds or pollen or eggs. And there are millions of ways they might get activated. DNA is certainly information, but it is replicated billions of times. There are billions of ways that DNA might hook up and produce the next generation. Billions of signals with certain receptors might be met with billions of possible counter-parts that have matching receptors. It certainly doesn't depend on one little piece of information hidden once somewhere, which somebody has to remember to go look for.

That is where our informational systems tend to go wrong. We put something in some suitable place, and then one is just supposed to know where to find it. And, oh, one can make all sorts of reminders that makes it easier. Like, if on the web a piece of information is stored in some place, other sites can link to it, and people can make bookmarks, and they can write a little note for themselves to remember where it was. And you can go search in a search engine. And that helps, and somehow most things work out. But it still seems vastly inferior in some way to the relatively effortless manner information is used in the natural world. Our systems depend on somebody remembering what to look for, at the right time, and discovering the right context. It is very fragile.

Just like our technology, which is built on similar models. One little wire is disconnected or one little comma in the wrong place in a program, and the car doesn't start or the space probe misses Saturn. Our constructions often have many single points of failure. Nature generally doesn't.

We can learn, I'm sure, from nature, how to help things link up more often, and more reliably. Of course what I really want is for the information I need to be available exactly when I need it. I want the information to come to me at the right time, and I want to not have to analyze large amounts of data to find out what is going on. I want to be reminded of my bill at a reasonable time to pay it, and I want the expectation of having to pay it to be wired to my budget somehow. I would want to know of course, the moment I try to buy something else frivolous that it would mean that I couldn't pay that bill next week. Well, really I'd rather not have a bill. I'd rather that my economic metabolism took care of the needed energy exchanges, continuously.

A lot of our information use carries with it the phenomenon of "Now the cake should have been in the oven for 1/2 hour". You know, you get to a certain point in the recipe and it tells you that there's something you should have done at an earlier stage, but you weren't aware of it at that stage. I might put a reminder in my calendar to pay a bill, and when it rings, I will remember that I should have made sure I had money to pay it. Which I might not have done.

Disjoined information doesn't necessarily add up. There's no guarantee it adds up to meaningful information and useful knowledge. Just because you spread a lot of screws and other mechanical parts around on the floor there's no guarantee you can construct a refrigerator from it. If I started with a working refrigerator and dismantled it, then I likely could. But independently aggregated bits and pieces, no. And most of our information is like that. It doesn't come from a dismantled whole, but rather from unrelated bits and pieces, which you're then supposed to put together into a whole. Which is next to impossible.

We are pretty good at managing anyway. Despite that we live in a sea of disjoined information, we're pretty good at creating some kind of network between them and making useful things happen. We do it in a rather primitive low-tech kind of way, maybe. Most countries have an enormous and ridiculously complicated system of law. Most people, including the politicians who wrote the laws, and the lawyers and judges who interpret them, do not at all have an overview of what it adds up to, and many laws contradict each other. So, for normal people the answer is usually to look around you and guess at what the laws seem to be. Stop for red lights, don't steal other people's stuff, etc. And the lawyers will just search for laws that support a particular point when the need arises. We find a pragmatic way of dealing with it, in the face of the impossibility of knowing what the laws actually say in total. So what do we really know, if the pieces are scattered all over, and we're just barely coping?"In what sense is a thing known if five hundred people each know one constituent of it and nobody knows the whole? Or again; what if this truth has a thousand constituents and half of them are not known to anyone, but only stored in libraries? What if all of them only exist in libraries? Is it enough that somebody knows how to look them up if they should ever be needed? Indeed is it enough that this person should have access to a system which will look them up? Does the enquirer even have to understand the questions which these truths answer?" - Mary Midgley (Wisdom, Information and Wonder: what is knowledge for? 1989) Is that really the best we can do? Can't it all connect better? Well, one possibility is a structured semantic web. If all information is meticulously categorized and related with all other information. Possibly in some huge all-encompassing hierarchy. I don't know how likely or possible or even desirable that is. Another possibility is making everything easier to find, and to constantly look for matches for everything. That's more like nature's way, I think. You put everything that needs to be remembered out in loads of redundant copies. And then loads of little pieces are constantly looking for matches to what they're looking for. You know, a Synchronicity Engine of some kind.

There's still some major key missing, though. We need a paradigm shift that takes us from the overwhelming complexity of scattered information to a world where things might again be simple, but at a new level. You know, you're hungry, there's an apple on the tree in front of you, so you eat the apple, and you feel good. That kind of simplicity. You're tired and you sleep. But while at the same time being globally connected with a vastly bigger network of people and information. Rediscover the simplicity in a higher order of complexity. I have no doubt that it is there. And if we don't find it, it is probably because we still address information complexity the wrong way.

[ Knowledge | 2004-07-18 10:15 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, June 28, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

What is a "polymath"? Dictionary.com: What is a "polymath"? Dictionary.com:

A person of great or varied learning; one acquainted with various subjects of study.

Polymath is from Greek polymathes, having learned much, from poly-, much + manthanein, to learn. You could also call it a comprehensivist. Waldzell:

A polymath, as defined here, is a person with the knowledge and expertise of a specialist in several, usually non-overlapping, domains of knowledge or expertise. A comprehensive polymath, or comprehensivist, is a polymath with the ability to synthesize knowledge and expertise from any combination of domains. Some definitions describe it as some kind of genius, but that is not necessarily the point, even if the most famous polymaths probably have extraordinary genius. Think Leonardo da Vinci. But the point is probably rather a wide range of interest and general knowledge, and a certain urge to tinker with different things. Polymath Society:The dictionary definition of a polymath is a very learned person, of encyclopedic knowledge. There is also the connotation of having an understanding deeper than that found in an encyclopedia, that is, an expert in many fields.

Anyone can be a polymath as long as he or she has the right motivation. A polymath is not necessarily a brain. In fact, a polymath usually does not think of his or herself as being particularly smart, only curious. Curiosity and interest are the true motivation for work, both intellectual work and the nitty gritty of hands on inventing. Thomas Edison said that genius is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration. He had a passion for getting his hands dirty, for tinkering, for inventing through trial and error. The polymath makes lots of mistakes. This is how new sciences are created. I haven't really used the word polymath much, but I've often said that I'm a comprehensivist. As mentioned, one sign might be one is skilled in several apparently unrelated areas. Which might seem puzzling to others, but which usually fits together as facets of a bigger picture, even if it might be invisible to anybody else but that person.

Of course, calling oneself a polymath or comprehensivist can also be a cover for scattering oneself over many subjects without really getting anywhere with any of them. A euphemism for Attention Deficit Disorder. Well, I'm gonna leave that alone.

The part I identify with is not particularly being a very learned person. I personally don't really have much to show for any extensive learning, certainly not in any academic field. Maybe rather the part about being able to synthesize knowledge and expertise from any combination of domains. Or the ability to span domains, and connect up different fields. People who only are specialists in one field might not notice the potentially valuable connections that field has with other very different fields. Somebody who has learned both fields might. But it is not necessarily needed to be thoroughly trained in both fields. It might simply be that one is tuned into looking for connections and synergies.

And it might be that one is looking for something with doesn't quite fit in any category, any specialized field. Something that is found in a lot of fields, but which also is a little beyond all of them. For example, a certain connection between all things. The patterns that the whole is moving in. Maybe a certain aestetic. A certain sense of something that needs to be expressed.

A few more recent writings on polymaths: Suw Charman wrote about A polymath in an age of specialists. Julian Elve about the Unpredictable Emergence of Learning. Mentions by Seb Paquet, Jim McGee. Julian adds up some key points: * Generalist / Polymath learning exists, contributes knowledge and helps the horizontal distribution of knowledge;

* The public, linked, asynchronous nature of blogs and related technologies both exposes conversations to a wider pool of people and helps the ideas start to flow before any face-to-face meeting;

* The benefits of any specific piece of knowledge are not always forseeable until the right combination of circumstances and other people arises – in other words unpredictable emergent behaviour;

OK, so we need people who go around combining things, poking into different fields, trying to connect things up. Agents of Emergence, I suppose. Looking for synergies, looking for things that might be possible. Or maybe just fluttering about and cross-polinating things by accident.

And, yes, clearly blogging in a useful tool for all of this.

[ Knowledge | 2004-06-28 15:37 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|