| Tuesday, December 2, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

I had certainly heard about it before, but I didn't realize there were a website before Seb mentioned it. The Stanford Prison Experiment in 1971 is one of the more enlightening and frightening demonstrations of how easily humans accept a fake reality as real, and act accordingly. College students volunteered to the experiment of acting as prisoners and prison guards in a two week experiment. The experiment had to be stopped after six days because it became way too real. 'Guards' turned into sadistic slave masters, 'prisoners' accepted their humiliations and had psychological breakdowns. Even the 'prisoners' parents, outside helpers like priests and lawyers, and even the psychologists running the experiment - all started treating it as reality and acting accordingly. The experiment was stopped because it was going so far that there was fear of people's health and sanity. But also because, for the first time, somebody walked in (another psychologist) and said "Hey, you have to stop this, you can't treat people like this". Until then everybody, including around 50 outsiders, had just gone along with it, and adopted the premises of the situation, even though they all knew that they weren't 'real'. I had certainly heard about it before, but I didn't realize there were a website before Seb mentioned it. The Stanford Prison Experiment in 1971 is one of the more enlightening and frightening demonstrations of how easily humans accept a fake reality as real, and act accordingly. College students volunteered to the experiment of acting as prisoners and prison guards in a two week experiment. The experiment had to be stopped after six days because it became way too real. 'Guards' turned into sadistic slave masters, 'prisoners' accepted their humiliations and had psychological breakdowns. Even the 'prisoners' parents, outside helpers like priests and lawyers, and even the psychologists running the experiment - all started treating it as reality and acting accordingly. The experiment was stopped because it was going so far that there was fear of people's health and sanity. But also because, for the first time, somebody walked in (another psychologist) and said "Hey, you have to stop this, you can't treat people like this". Until then everybody, including around 50 outsiders, had just gone along with it, and adopted the premises of the situation, even though they all knew that they weren't 'real'.Less than 36 hours into the experiment, Prisoner #8612 began suffering from acute emotional disturbance, disorganized thinking, uncontrollable crying, and rage. In spite of all of this, we had already come to think so much like prison authorities that we thought he was trying to "con" us -- to fool us into releasing him.

When our primary prison consultant interviewed Prisoner #8612, the consultant chided him for being so weak, and told him what kind of abuse he could expect from the guards and the prisoners if he were in San Quentin Prison. #8612 was then given the offer of becoming an informant in exchange for no further guard harassment. He was told to think it over.

During the next count, Prisoner #8612 told other prisoners, "You can't leave. You can't quit." That sent a chilling message and heightened their sense of really being imprisoned. #8612 then began to act "crazy," to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control. It took quite a while before we became convinced that he was really suffering and that we had to release him. This is all rather horrible stuff, but very illuminating about our human tendency to be 'normal' and do what we think the circumstances demand of us. The experience of those volunteer prisoners in 1971 is, unfortunately, also very comparable to the experience that millions of real prisoners go through. And nobody's going to walk by and stop that experiment because it isn't right to treat people that way. Two million people are in prison in the United States.

Ironically, it was less than a month after the Stanford experiment, that the infamous riot broke out in Attica Prison in New York. The prisoners were demanding basic human rights. Instead New York's governor, Nelson Rockefeller, sent in the National Guard to take the prison by force and many guards and prisoners were killed.

[ Patterns | 2003-12-02 09:19 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, November 30, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Interesting article from 1997 by Howard Bloom about how our reality is formed and manipulated by what we hear, what we remember, what other people seem to believe, etc. Not just that our memories and peer pressure is influencing and coloring how we see the world. No, much more tangible than that. We physically perceive that which we assume we'll perceive and that which we've been conditioned to perceive. I particularly find experiments such as these fascinating: Interesting article from 1997 by Howard Bloom about how our reality is formed and manipulated by what we hear, what we remember, what other people seem to believe, etc. Not just that our memories and peer pressure is influencing and coloring how we see the world. No, much more tangible than that. We physically perceive that which we assume we'll perceive and that which we've been conditioned to perceive. I particularly find experiments such as these fascinating:In the late 1970s, Loftus performed a series of key experiments. In a typical example, she showed college students a moving picture of a traffic accident, then asked after the film, "How fast was the white sports car going when it passed the barn while traveling along the country road." Several days later when witnesses to the film were quizzed about what they'd seen, 17% were sure they'd spied a barn, though there weren't any buildings in the film at all. In a related experiment subjects were shown a collision between a bicycle and an auto driven by a brunette, then afterwards heard questions about the "blond" at the steering wheel. Not only did they remember the non-existent blond vividly, but when they were shown the sequence a second time, they had a hard time believing that it was the same incident they now recalled so graphically. One subject said, "It's really strange because I still have the blond girl's face in my mind and it doesn't correspond to her [pointing to the woman on the videotape]...It was really weird." In visual memory, Loftus concluded that hints leaked to us by fellow humans are more important than the scene whose details actually reach our eyes.[...]

It was 1956 when Solomon Asch published a classic series of experiments in which he and his colleagues showed cards with lines of different lengths to clusters of their students. Two lines were exactly the same size and two were clearly not - the mavericks stuck out like basketball players at a convention for the vertically handicapped. During a typical experimental run, the researchers asked nine volunteers to claim that two badly mismatched lines were actually the same, and that the actual twin was a total misfit. Now came the nefarious part. The researchers ushered a naive student into the room with the collaborators and gave him the impression that the crowd already there knew just as little as he did about what was going on. Then a white-coated psychologist passed the cards around. One by one he asked the pre-drilled shills to announce out loud which lines were alike. Each dutifully declared that two terribly unlike lines were perfect twins. By the time the scientist prodded the unsuspecting newcomer to pronounce judgement, he usually went along with the bogus acclamation of the crowd. Asch ran the experiment over and over again. When he quizzed his victims of peer pressure, it turned out that many had done far more than simply go along to get along. They had actually shaped their perceptions to agree, not with the reality in front of them, but with the consensus of the multitude.[...]

Another experiment indicates just how deeply social suggestion can penetrate the neural mesh through which we think we see hard-and-solid facts. Students with normal color vision were shown blue slides. But one stooge in the room declared the slides were green. Only 32% of the students ended up going along with the vocal but misguided proponent of green vision. Later, however, the subjects were taken aside, shown blue-green slides and asked to rate them for blueness or greenness. Even the students who had refused to see green where there was none in the original experiment showed that the insistent greenies in the room had colored their perceptions. They rated the new slides more green than they would have otherwise. More to the point, when asked to describe the color of the afterimage they saw, the subjects often reported it was red-purple - the hue of an afterimage left by the color green. The words of one determined speaker had penetrated the most intimate sanctums of the eye and brain. So, does that mean we're all just gullible sheep who're walking around in a trance, thinking we see things that aren't really there? Well, to some degree, yes. But we can start becoming conscious of our processes of perception, aware of how realities are generated, and we might actually catch when we're being mislead by words or memories or other abstractions. And we might learn to always expand our sense of reality, reaching beyond the hallucinations generated by our assumptions, beliefs and memories.

[ Patterns | 2003-11-30 07:14 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, November 3, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

There are two methods of logical reasoning that are often contrasted with each other. There are two methods of logical reasoning that are often contrasted with each other.

Here's deduction. That's when A leads to B that leads to C. Or A + B leads to C for that matter. You try to follow a logical sequence, trying to include all the facts and weeding out any variables, in order to logically prove the inevitable conclusion. Because this is true, then that must be true, and therefore we can conclude so-and-so.

These are some of the problems with deduction:

A. The human mind is badly suited for including all relevant facts. We use pattern matching to make sense out of anything, so no matter what we think is concise, comprehensive and logical, it most likely isn't.

B. The human language is not precise. Words are abstract, and different people don't mean exactly the same by them.

C. Deduction can fairly easily be manipulated by providing or revealing only those elements that will support a given conclusion.

Then there's induction. That's where you make a mental leap and guess at the conclusion first, and then you go and check if it fits with the facts at hand. And, presumably, if you succeed in coming up with a theory that fits all the facts and hand, and that can be repeated and verified, then you've got a good answer. Or you'll find out that your hypothesis is wrong, because it doesn't explain the facts you see. Then there's induction. That's where you make a mental leap and guess at the conclusion first, and then you go and check if it fits with the facts at hand. And, presumably, if you succeed in coming up with a theory that fits all the facts and hand, and that can be repeated and verified, then you've got a good answer. Or you'll find out that your hypothesis is wrong, because it doesn't explain the facts you see.

Some of the problems with induction are:

A. The human mind is also rather badly suited for coming up with original explanations that aren't based on what previously has been fed in.

B. If one starts believing the inducted idea, there's a tendency to filter out any data that doesn't fit it, and it doesn't actually get verified.

And there's a problem with both that they're all just good guesses. You can be good at logic, and follow stringent steps of analysis and reasoning, and consistently come up with good predictions, much superior to blind, random guesses, but they're still really just qualified guesses.

Good science uses both deduction and induction. You use induction to come up with new theories that might explain more things, and you do experiments and deduct what they're showing you.

Bad science does roughly the opposite. E.g. make new theories and forget to verify them properly. Or, deduct from previous theories in order to conclude what's impossible and therefore shouldn't be explored. And rule out new theories because they don't fit with the old theories. You know, "planes can't fly because they're heavier than air", or "we won't see any extraterrestrials come here because it is impossible to travel faster than light".

Personally I like using deduction for solving puzzles, and I tend to be good at drawing the logical conclusion from data that is available. But to create my picture of the world, I much prefer to use induction. I.e. I search for, or imagine, the models that will explain more of the world I know than the models I previously used. And which I can verify by experiment in my own life, and/or which will better predict events than the alternative models. I recommend it.

But watch out for people who would like to sell you more limiting world views and explanations, based on that they have been "proven" and yours have not. The logical wires have been crossed a bit there. If you have a model or world view that allows you to successfully understand, explain and predict many things, don't buy a model that explains and predicts less, no matter what authority backs it up, or questions yours.

Astrology is a fine example there, particularly because a lot of people will think that it isn't. If you're a skilled astrologer who can probably successfully understand and explain and predict lots of things about people, you might once in a while run into an angry scientific type who insists that it is a big fraud, and you're an idiot, because nobody's found any mysterious rays from the planets that are controlling people. And he's typically implicitly inviting you to drop your large vocabulary of patterns and archetypes and relationships, and replace it with, essentially, the belief that you can't really predict anything much about people's lives and personalities, and random data and luck is about the best you can get. Is that better? If astrology actually works for you, obviously no. If it doesn't, maybe you should keep looking. Reading tea leaves is not necessarily better than checking out the available facts.

The test is of course whether it works. The most satisfying, all-encompassing, verifyable, workable, simple explanation is the better one. That it is big and complex doesn't make it better. Simpler is better. But the point is to use the model that works best for you.

So, what about, say, religious explanations? Well, if you're actually reasoning yourself conscioiusly towards a more complete cosmology, the same rules apply. If you're accepting somebody else's explanation, you might very well be subject to the pitfalls mentioned above. I.e. you get to see exactly what you expect to see and nothing else. Specifically religious discourse seems to be fruitful ground for the circular kind of reasoning, where you logically 'prove' to yourself that the foundation for your belief is sound, simply by starting with a datum and coming back to it a little later. So, what about, say, religious explanations? Well, if you're actually reasoning yourself conscioiusly towards a more complete cosmology, the same rules apply. If you're accepting somebody else's explanation, you might very well be subject to the pitfalls mentioned above. I.e. you get to see exactly what you expect to see and nothing else. Specifically religious discourse seems to be fruitful ground for the circular kind of reasoning, where you logically 'prove' to yourself that the foundation for your belief is sound, simply by starting with a datum and coming back to it a little later.

You know, "Jesus died for MY sins, so I really owe him to listen to his words, and what he says is in the bible, so it must be true, because he said it, and it says that he died for my sins." A mix-up of what is the hypothesis and which is the data.

"Nothing can travel faster than light because we have a theory that says so, so therefore we aren't looking for it, and therefore we haven't seen anything do so, and therefore it is proven."

Evolutionists versus Creationists is probably another area where you'll find plenty of circular reasoning, where you prove your point by your own arguments.

One way or another, there isn't quite any logical panacea that you can prove everything with. Developing a useful picture of the world is done with some mixture of an open mind, your own intuition, keen observation, experimentation, luck, good advice, access to good data, verificaton of the validity of data AND some discipline of logical reasoning.

[ Patterns | 2003-11-03 13:27 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, October 28, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Bernard Wisser says some good stuff in relation to how you can "Stand still and look until you really see", about how to get beyond the habits that keep us stuck in seeing the world in old ways. Bernard Wisser says some good stuff in relation to how you can "Stand still and look until you really see", about how to get beyond the habits that keep us stuck in seeing the world in old ways."Practices can be used not only to expand the mind but to shrink the ego and bringing into a proper proportion in influencing our behavior or curing it of its pathology. There seems to be an inverse relation between mind expansion and ego diminishment. There is also an intimate relationship between left brain activity and ego in their attempts to insure our survival. They are both very involved in the pre-perceptual and perceptual process. Unfortunately, in order to stabilize a world (even a universe) that is in constant process, so we can operate more effeciently in it, in a material and practical way, the right brain alliance has formed a whole barrel of HABITS (not very good).

Habit formation is what prevents from being here now. You can of a habit as a behavioral packet in which the Past (behavior or meaning or understanding or catagorizing) is repeated in the Present when confronted with a "similiar" situation, in order to insure your Future as you planned it to be in the Past. Notice the emphasis on similiar that matching is done both before and after perception in the process of organizing are world. So what we experience most of the time is what we have become conditioned to as important for our survival, maintainance, and growth." And he has an exercise. So go practice experiencing things a different way than you have before.

[ Patterns | 2003-10-28 17:30 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, October 22, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

We seem to form our picture of reality based on a pattern matching algorithm. It doesn't really matter if you consider that a function of neurology or as a deeper metaphysical principle, the result it about the same.

If "enough" pieces of a reality are assembled and they are recognizable and familiar to us, we assume that the remaining details are probably also in place and that we're dealing with a "real" reality. If "enough" pieces of a reality are assembled and they are recognizable and familiar to us, we assume that the remaining details are probably also in place and that we're dealing with a "real" reality.

It is perfectly possible to fool people into accepting a scenario as reality that really isn't, if you put enough familiar elements into place. Most candid camera episodes are built on that kind of principle. An environment is set up so that it looks like you've been hired for a new job, and there's a real office and other employees and everything. And then a surprise element is thrown in, like the arrival of a stripping telegram, or the need to handle some impossible problem, like your desk falling apart. And the "employee" accepts it as real, because everything else looked right.

Or how about experiments that were done where a comedian managed to get up in front of a medical convention and give a speech in complete giberish without anybody noticing. Because he looked right, and sounded right, and even though the attendees where highly educated M.D.s they were also used to not having to understand all the details of what everybody was saying, and they were used to displaying a certain respect towards their peers. The Emperor's New Clothes. We're all trying to act normal, unwilling to admit we don't understand everything.

Conversely, we can also create an invisible reality, if it is constructed of elements that are so unfamiliar and unexpected that we just can't see it. A stage magician is usually quite adept at that. You don't see what he's really doing because you're not attuned to the patterns he's using. Conversely, we can also create an invisible reality, if it is constructed of elements that are so unfamiliar and unexpected that we just can't see it. A stage magician is usually quite adept at that. You don't see what he's really doing because you're not attuned to the patterns he's using.

It is said that when Captain Cook's ship first approached the island of Tahiti in the South Pacific, the inhabitants could literally not see it coming. Even when Cook and his crew got out and pointed out their ship to the Tahitians, and explained how they arrived, the natives couldn't see the ship at first. Because it was totally unfamiliar and they didn't have any belief that included the possibility that somebody could arrive from the ocean in a large sailing vessel.

In our modern society we tend to walk around believing that we're very rational and observant and we've got a pretty good grip on what is reality. Science tends to create that picture. But yet, science, however useful it is, is just a systematic way of agreeing on what a certain reality is, and how to get predictable results with it, and it tends to stay within the boundaries of those codified agreements, often ignoring anything that doesn't fit. Science only very cautiously and gradually will expand that area.

If you master these principles, and you have sufficient resources at your disposal, it is entirely possible to both create fake realities that large numbers of people will accept as the truth, as well as to create realities that are invisible to the general population.

Think for example of a black project that has access to sufficiently advanced principles and technologies that have been kept out of the public knowledge, out of scientific text books, and out out of the educational system. Say, teleportation or time travel. You don't even have to worry much about leaks, because they will pretty much be self-healing. If somebody puts out a story about secret time travel experiments, it is very easy to ridicule them, and you don't even have to do it yourself, as there will be plenty of respectable scientists and good citizens who'll stand up and say that it of course is impossible and complete nonsense. Somebody could even write a book with all the details and you could pick it up in the UFO section of your local bookstore, but it wouldn't sink into the public awareness as anything real.

You can keep very big things very secret if you just make sure that enough of the components and participants are far enough removed from what is normal and expected, and the facts are generally so hard to get to, and so hard to piece together, that the whole thing becomes invisible to most people.

Single secrets hidden by known people can fairly easily be discovered. But complex secrets, put together from many individually incredible elements, those are much harder to bring to the light.

Conversely, you can make fake stories appear very real and accepted if you just make sure that you provide enough components of normal reality. Like, pictures, sound, stories, information, and lots of it, and repetitive delivery of it. And that the people presenting it look like the right kind of people to do so. Reporters, scientists, government officials, etc.

I'm not really even talking about conspiracy theory particularly. A bigger view than that. Conspiracies are usually imagined as something the known and accepted players are doing when you aren't looking. Like, does George Bush and Tom Brokaw and Kenneth Lay and everybody else you see on the news have secret meetings where they plan out how they'll fool everybody? Well, maybe they do, but that's probably not where it is really at. Whatever specific things they do will quite likely come to light sooner or later and would be too hard to hide. What matters is not what they did, but what reality we end up accepting, and which realities we'll ignore. The real secret stuff would probably be going on in places you don't even know to look at, and would be done by people you've never heard of. And the people you are looking at on the news are quite likely thinking they're just doing the best they can with what's available to them. Because they probably live in a manufactured reality as well.

[ Patterns | 2003-10-22 05:15 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, October 21, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

If you're trying deliberately to think creatively, to come up with new ideas, having a set of stimulating tricks can help. It is quite possible to stimulate lateral thinking in fairly mechanical ways. Lateral thinking is where, instead of following the usual step-by-step logical paths of thinking, you sort of jump to the side and come up with something entirely unexpected. Ed de Bono is one of the champions of lateral thinking. If you're trying deliberately to think creatively, to come up with new ideas, having a set of stimulating tricks can help. It is quite possible to stimulate lateral thinking in fairly mechanical ways. Lateral thinking is where, instead of following the usual step-by-step logical paths of thinking, you sort of jump to the side and come up with something entirely unexpected. Ed de Bono is one of the champions of lateral thinking.

An effective and well-known way of provoking lateral thinking is to introduce a random element. For example, while closing your eyes, open up a dictionary and point somewhere on the page, and see what word it is. And then pretend that it has something to do with your problem at hand, and try to figure out how. And some percentage of the time, you'll actually come up with surprisingly good ideas. If you have no problem or idea to start with, you can pick up two words by that method, and then pretend that they relate to each other, and sometime you might actually invent something new.

Arthur Koestler talked about "bisociation" which is the theory that new ideas arise from the combination of two previously separate ideas. I.e. you combine some things in a way that hadn't been imagined before, and to your surprise you realize they actually fit, and a new idea, or a new invention, might come from it. One can practice this simply by taking random words, items or subjects, and exploring what happens if they're combined.

If you do have an idea or problem or invention you're exploring, which looks promising, or which presents an obstacle, there are many things one can do with it to look for creative ways of making it work. Supposedly victorian engineers would work designs for new machines through a checklist of ways it could me done differently, mechanically speaking, and new, better ways might emerge. Some of the same tricks can be applied to most new ideas, even if they aren't exactly about a mechanical invention.

Magnify it; Reduce it.

Reverse it; Spin it; Re-orientate it.

Turn it inside out.

Heat it up; Cool it down.

Move it forward; Roll it backward.

Raise it; Lower it.

Move it left; Move it right.

Project it; Inject it.

Squeeze it; Expand it.

Replicate it; Decimate it; Weed it out.

Make it portable; Make it importable.

Speed it up; Slow it down.

Age it; Rejuvenate it.

Transpose to the past or the future.

Change from analog to digital.

Implement it in hardware or software.

Be it; Do it; Have it.

Take it apart; Put it together

Make it heavier, lighter.

Centralize it; De-centralize it.

Grow it; Design it

Focus on it; Make it peripheral.

Explode it; Implode it.

Wear it, live in it, sit on it, transport it, eat it.

Color it, add sound, touch it.

Take on its identity, what does it feel like, what does it want to do?

Split it in complementary parts, or put it together with its counterparts.

If this exists, what else would exist?

Make it transparent, clear, fuzzy, opaque.

Energize it; Tap its energy.

Make it 1-, 2-, 3-, or 4-dimensional.

Make it have two states (on/off), or have infinite grades.

Put in water, underground, in the air, or in space.

Pressurize it; put it in vacuum.

Make it weightless; increase the gravity.

In other words, play with the new idea or the problem at hand. Stretch it, bend it, turn it upside down, inside out, in any way you can think of. And you might realize that what didn't work on a large scale might work on a small scale, and what didn't work one way might work the opposite way.

Also, when you play with actual perceptions, you're making things more real. Purely abstract ideas have less chance of materializing than if you can actually see them, feel them, hear them, smell them, taste them.

See an old article by Keith Hudson that inspired this article here.

[ Patterns | 2003-10-21 05:33 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, October 6, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Another pattern.

In contexts where a person or group is behaving in a certain fashion, which they potentially should be able to control:

Deliberate change can only happen when you can distinguish what you previously have been doing.

Said a different way, you need to be able to see something a bit at a distance before you really can notice it, and articulate it, and then change your mind about it, and choose a different path.

You can't change something you are BEING

You can only change it after you, at least for a moment, step back and perceive it from a meta-perspective. You dissociate from the state of being.

Whether you can talk about the subject matter or not is part of the equation. If you don't have language to talk about a certain kind of situation, you're not very likely to be able to decide to change it. If you have words for it, or if you have a mental model for it, a mental abstraction for it, then you can make a decision about it.

And, to change into a different mental model, a different paradigm, one needs to be able to perceive that paradigm. One needs to be able to examine it, and say something about it. So, there are a lot of possibilities that aren't really available, just because they are so far removed from one's normal frame of reference that one just can't see it.

You can only change into a new state if you can perceive it as a possibility

Of course I'm only talking about conscious, deliberate change here. One can change other ways too. External circumstances might suddenly hit you in ways you didn't expect. Evolution might happen without your conscious involvement.

(Gee, I could use a drawing pad. Drawing with a mouse sucks)

[ Patterns | 2003-10-06 14:29 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, October 3, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

I'm trying to practice noticing patterns, and writing them down. Here's one. I'm trying to practice noticing patterns, and writing them down. Here's one.

In circumstances involving multiple humans, where one of the people has a level of influence or authority, and where there is a certain identifiable desirable activity that the other one or more people need to engage in, one of the simple sets of rules that the authority person can operate by are:

If things are happening, don't change anything

If things are not happening, change something.

That is not always as self-evident as it sounds, so it can be useful to spell it out.

It says to not mess with processes that are already doing the right thing. Despite that they might not be doing it the way you had in mind. If it ain't broke, don't fix it. And it says that if you aren't getting the desired result, you shouldn't just sit and wait, you need to do something, or change something, so that a different process takes place.

I know this principle from my work as a counselor. There's a certain something that needs to take place with the client who comes in and sits in the other chair. They need to change for the better, they need to become more resourceful, they need to be more able to overcome their problems, they need to be happier, and look positively towards the future, etc. And there are certain components or steps that usually are part of that. They need to be willing to sit still long enough. They need to be able to be a little introspective and actually examine themselves and their thoughts and reactions. They need to be able to come to some realizations. And willing to change their mind and do things in a new way. It is my job as the counselor to make sure they're doing these things. If they already are, I don't have much to do. If they don't, I have to come up with a way of getting them back there. If the client sits down and keeps talking about the weather and last night's TV, then things aren't happening, and I need to come up with a way of switching us into a different track. But if they come in, sit down, and right away start getting into some deep and productive self-examination, which they then come out of with a big realization and a new more useful pattern in life, and a better outlook on the future - hats off to them, and I don't have to change anything. Makes sense?

Or think about a strategy for entertaining a small child, while you're busy with other activities. If she's sitting down happily occupied with something that isn't dangerous to her, great, leave her alone. She's already entertained, so no need to change anything. But if she's suddenly bored and getting in your way, ok, it is time to change things. Which might mean to introduce something new and different. Hey, here's another toy, or, wow, you can draw with these pencils, or how about we go into the other room, or try to tie your shoe laces. Every good mother knows these things of course. It doesn't help to keep saying "don't bother me!" Get creative and bring in another factor that will make the child get interested, entertaining herself. After which you can happily leave her alone for a while. Keep some extra surprises in your bag for the next time the child gets bored, and you can do your job fairly easily.

Said a different way:

Don't keep doing things that aren't working. (even if you think they're the 'right' things to do)

Keep doing things that ARE working. (even if they weren't supposed to be working that way)

Duh! What gets in the way is usually fixed ideas about how things are 'supposed' to be done, and a failure to recognize whether the desirable outcome actually is or isn't taking place.

Here's another way:

If you aren't getting the desired result, DO something, anything.

If you ARE getting the desired result, do nothing. Relax and enjoy it.

and of course, all of this requires that you:

Know what is the desired outcome in the circumstances you're in.

[ Patterns | 2003-10-03 14:52 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, September 28, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

I'm going to make a more concerted efforts to collect patterns. It is something that well summarizes something I care a lot about. I'm talking about patterns that make things work well, in contrast to patterns that don't work well. Uplifting patterns, transformative patterns, generative patterns, ecological patterns, synergetic patterns. I'm going to make a more concerted efforts to collect patterns. It is something that well summarizes something I care a lot about. I'm talking about patterns that make things work well, in contrast to patterns that don't work well. Uplifting patterns, transformative patterns, generative patterns, ecological patterns, synergetic patterns.

It is an activity that probably doesn't make sense to everybody. A meta level of dealing with the world. But patterns are essentially a way of successfully navigating an otherwise confusing world. A pattern is the way things are arranged. Without worrying too much about the exact things that are arranged, one concerns oneself with the arrangement they're in. Structure as opposed to content.

I know that very well from my work as a personal counselor. NLP is essentially all about patterns. Discovering what patterns people think in, and how they do things. And then either using the existing patterns for doing what one really wants to do, or adjusting the existing patterns so they work better.

E.g. many people have a pattern in their mind where they make clear pictures of something, and then they get a strong feeling about it, and then they tell themselves things that reinforce a course of action about it. If they make the clear pictures of something they actually want, and they get an energized feeling about it, and tell themselves encouraging things about it, they might be very productive and effective. But if they make pictures of what they don't want, and get freaked out about it, and then feed themselves pessimistic and discouraging statements about it, they might just be a mess. It is the same pattern, but depending on what content you put into it, it might be more or less useful.

Procrastination is a pattern that usually doesn't work well. One notes something that needs doing, and one places it out in the future somewhere, and then it feels like one has cleared space for doing something else in the present. The thing to do pops up once in a while, presenting itself with some kind of bad feeling, and one lessens it by again putting it out in the future. One can either change that pattern, by putting things into a different order, or one can use the pattern itself, and, through a kind of mental judo, realize that one can just procrastinate "later". Try it sometime. You can procrastinate tomorrow.

Anyway, now I'm also interested in patterns of personal organization, business, and group collaboration.

A website has things arranged in a certain way, and that way will greatly influence how people use the site, and what is accomplished. Apparently tiny details that are casually decided at design time might have enormous consequences later. For example, some things I've noticed are: If you make a list of people or weblogs, sorted by update time or popularity or something else like that, people will get into a competitive mode in order to end up on top of the list. And/or others will start feeling differently about the people who happen to be at the top. And I've noticed that if you list a bunch of items, like people or websites or weblogs, in one place, in one list, people will start believing that they have a relation to each other, even if they don't. If you put an item on top of a page, people will consider it more important than it it is at the bottom. Many of these observations are "duh, of course!" kinds of realizations. It is simple in retrospect, but not necessarily in advance.

Here's an article: "an Building Communities with Software" by Joel Spolsky about a number of the design issues in community software, which contains many intelligent observations. If you put a button people need to click on at the bottom of the page, below a bunch of entries from other people, it is more likely that those entries will be read. If you send people in e-mail responses they've gotten to messages posted in some forum, it is much less likely they'll go and browse around there. The design choices in Usenet readers makes for long-winded threads that people lose track of the start of. The mechanics of IRC groups makes for lots of effort spent on fighting for specific group names and handles. All because of the patterns things are arranged in.

Chris Alexander talked about "Pattern Languages" as it applies to architecture of buildings. And it has spread to software.

But we need pattern languages in all aspects of life.

There are patterns for organizations, which can be well represented in system diagrams. Gene Bellinger has an exellent page, "Mental Model Musings", containing lots of system diagrams for organizations.

Various good people are thinking about Uplift Pattern Languages.

For a while I would draw diagrams of patterns I noticed in a book I kept next to my bed, the same that I wrote dreams and good ideas into. I will continue that habit.

[ Patterns | 2003-09-28 15:44 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, August 29, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

There's an ongoing conundrum I have in my life, about how to both do good things that need to be done, and also happen to make a living from it. There's an ongoing conundrum I have in my life, about how to both do good things that need to be done, and also happen to make a living from it.

Let me address it from a different angle, and provide an answer, even though it isn't one I entirely like.

I will often lean towards the new agey concept that if I just put good thoughts and works out into the universe, I will naturally be supported or rewarded in return.

It is a bit like putting a message in a bottle and throwing it into the ocean, and hoping somebody will find it and that something comes back. And if I'm in a bit of a hurry I'll just kick out a whole bunch of bottle messages.

I happen to have done that enough to know that it works. However, it is also very indirect, the results are unpredictable, and they happen by a timing I don't control.

Now, the more sensible, practical and grounded alternative is that I more directly create that which I want to happen.

If I want water, should I sit and pray for it? Should I write extensively about my problems finding water? Or should I just dig a well?

If I want to go to the movies, do I sit down and make positive affirmations, and visualize that somebody will come and take me to the movies? Or do I just get on the bus and go to a movie theatre and buy a ticket?

Things happen when you do something that makes them happen. Some activities are much closer to the target than others. If I want water, starting in the desert might be a bad idea. If I want to bake bread, a screwdriver is not the best tool. If I want my garden to grow, writing doesn't help.

Same thing with money. You make money by doing something that makes money. Duh. Certain activities in certain settings make money. Others don't. If you want money, you need to do some of those activities that make money, in the manner and in the environment where they happen to work. You are free to invent something new, but it has to work.

One of my skills is as a computer programmer. That can be a potentially lucrative and rewarding thing to do. However, that doesn't mean that if I just start programming, I'll automatically be rewarded handsomely. Not any more than a ditch digger will be rewarded for just starting to dig. You need to dig in the right place, a ditch that will be useful to somebody, and they have to agree to compensate you for that.

There's a structure to making things that work. Not just one structure. The trick is to find the structure that works under the circumstances. If you need to build a bridge over a chasm, you need to analyze the geology, the wind conditions, and many other things, and you need a considerable amount of knowledge and tools to create the right design. And considerable skill and manpower to actually build it, with the proper materials and techniques. Then the bridge will work, and you can drive over it. If you screwed up one of the steps, or your plan wasn't connected with the real world, it just wouldn't work.

So, some of the ways NOT to make money are:

don't do anything

don't make up your mind what you'd want to do

don't make any moves towards what you'd like to do

become skilled in something that isn't very needed

pick a profession that is badly paid

go somewhere where your skills aren't needed

don't mention to anybody what you can do

don't feel like working

don't ask for money when you do something

demand conditions that aren't available

sit down and wait

complain a lot

don't contact the types of people you'd like to pay you

don't do a good job when you have one

do something else than what is needed

You get the point.

It is a disconnect I know very well from my work as a counselor. Many people aren't getting what they want, because they just haven't connected A to B, and they didn't notice. "I'd really like to go out with Joleen, but she's not paying attention to me", "Well, did you ever try talking to her?", "..eh, no".

So, the short answer is:

get clear on what you want to do

make sure it is possible and needed

find out how to do it

find out where best to do it

go and do it

if it isn't working, learn why and adjust your approach

Very simple. So, as to money, money isn't made by being a nice guy, or even by doing good work. It is part of it. But money is made by making a profit, by getting something cheap and selling it for more. If you don't know how to do that, you hook up with somebody who's doing that, with you as part of the input or output. Which is called a job, or a contract, or a pension, or whatever.

The how-to is often hidden, particularly when we're talking about money. The people who know how will often not tell you, or will give you a cover story. The cover story will often sound like the new age supported-by-the-universe story. I.e. that they're just thinking positive, doing good work, and money just flows to them. Not to put it down. Being positive and doing good work is great. But the secret is often that, under the hood, something else is going on. People did some much more specific things to arrive at where they are at. Maybe some of them are coincidental and can't easily be repeated. But often there's a specific structure to what people do or did in order to make their lives viable. Not any one universal structure, but many different structures. All of which you can learn from. There's always some key details there.

I'd personally much prefer if I didn't have to figure out money making. I'd much rather just walk around and do what I'm inspired to do in life, and then receive a stipend from Universal Resources. It isn't fair.

There's obviously several schools of thoughts here. What I'm talking about here is the approach of figuring out the HOW and then doing it. That is contrasted with the approach of emphatically ignoring the how, but concentrating on the WHAT. Build it and they will come. Dream the dream well enough, and the details will fill themselves in. Each school of thought is a little distasteful to the other.

[ Patterns | 2003-08-29 11:42 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, June 26, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

I really like randomity. In many programs and webpages I've made, there are some elements of randomity. Whenever you come by, there's a different quote, a list of names is sorted differently, a picture or a color is different. That's of course easy to do when there's a script that generates the page. A random number is generated and it is used to pick a record out of a database. Often it is a subtle or minor element I make random, but I always enjoy the result. I really like randomity. In many programs and webpages I've made, there are some elements of randomity. Whenever you come by, there's a different quote, a list of names is sorted differently, a picture or a color is different. That's of course easy to do when there's a script that generates the page. A random number is generated and it is used to pick a record out of a database. Often it is a subtle or minor element I make random, but I always enjoy the result.

What I like isn't really the randomity. See, I don't even believe in randomity. I believe in emerging order.

Sometimes you need to collide with a piece of chaos before you notice the pattern that is latent in it. Sometimes we need to shake things up before we start seeing new potential order.

There's the old creativity trick of closing your eyes, opening the dictionary and picking out one or two words at random. And then pretending that it wasn't random, and seeing how these words might help you stimulate a solution to some problem you're working on now. Very often surprising insights will emerge. In part because you get out of your fixed mindset and start looking at a much wider sphere of possibilities.

You can often get the picture of something much faster by throwing in some randomity than by examining it "systematically". If you're playing minesweeper, it is a bad strategy to start at one corner and move up one cell at a time. Better to try some random cells and see what picture forms. If you were trying to make out the topography of a piece of land, you might get the picture much faster by choosing a bunch of scattered random points to check than if you start at one end and go through it.

It is an intelligence or investigation technique as well. You might often find out more about a person or group if you pick some random or incidental channel of communication and see what goes through it, or some random source of information. Looking through somebody's trashcan would tell you a whole lot about them. Possibly more than if you just listened to them.

Divination works in a similar way, although it would look for more ethereal patterns. The idea is that life leaves traces and clues, and if one holds the view that everything in the world is inherently connected at a deeper level, it is quite natural to assume that the application of a little randomity might bring out some of the clues. Particularly if you know what patterns to look for. Shuffle your tarot cards and shake up some tea leaves, or listen to the itch in your left knee. They might be just the antenna you need to pick up some signals you might have missed otherwise. Particularly because, and not despite, that they use randomity.

What I'm talking about here is in part synchronicity. The discovery of meaning in coincidences. Which is a horrible and insane thought to people who believe that everything in the universe is inherently random, separate, unrelated and meaningless.

And it is a beautiful thought to people who believe that the universe and all life is connected, and who enjoy the emergence of previously hidden patterns.

So, I'm looking forward to many more chance meetings, surprising coincidences, never-before-seen connections, cross-disciplinary discoveries, emerging patterns of synergetic order. And whenever there aren't enough of them, I think it is time to roll the dice and shake things up.

[ Patterns | 2003-06-26 03:37 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, April 20, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

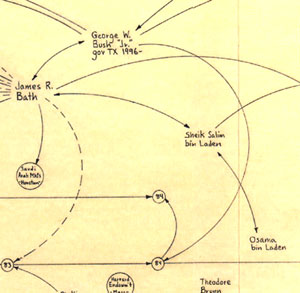

Weblogsky mentions the late Mark Lombardi who created hand-drawn network maps, which he called "narrative structures". They show the relationships between political figures and financial fraud, criminal activity, busted banks, etc. Weblogsky mentions the late Mark Lombardi who created hand-drawn network maps, which he called "narrative structures". They show the relationships between political figures and financial fraud, criminal activity, busted banks, etc. "At some point in my development," says the artist, "I began to reject reductivist approaches in favor of one capable of evoking the complexity, venality and occasional brutality of the times. What emerged was a study of 'irregular' financial transactions, with special emphasis on those undertaken in secret by select groups of influential yet silent partners." I think there ought to be a well financed team of independent investigatory journalists doing nothing but creating such maps all the time, with supporting information, and posting them on the net. Show us how things connect. Because they do.

[ Patterns | 2003-04-20 23:21 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, April 5, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

From an anthropology research paper

"Both laboratory and field data suggest that people punish noncooperators even in one-shot interactions. Although such "altruistic punishment" may explain the high levels of cooperation in human societies, it creates an evolutionary puzzle: existing models suggest that altruistic cooperation among nonrelatives is evolutionarily stable only in small groups. Thus, applying such models to the evolution of altruistic punishment leads to the prediction that people will not incur costs to punish others to provide benefits to large groups of nonrelatives. However, here we show that an important asymmetry between altruistic cooperation and altruistic punishment allows altruistic punishment to evolve in populations engaged in one-time, anonymous interactions. This process allows both altruistic punishment and altruistic cooperation to be maintained even when groups are large and other parameter values approximate conditions that characterize cultural evolution in the small-scale societies in which humans lived for most of our prehistory." Hm, so if I understand it right, most people will punish non-cooperative anti-social behavior when they have the chance, even if they have nothing directly to gain from it, and even if it doesn't produce visible increases in cooperation. And that people mostly have succeeded in collaborating in small groups, but not so much in large groups. Well, what I get out of that is that people are looking for widespread cooperation, and they're making choices to support it, but the right tools for crystalizing it haven't quite appeared yet.

[ Patterns | 2003-04-05 23:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Thinking is one subject I'm really interested in. Our ability to think abstractly is one of the key traits that define what a human is. Yet we seem to have little clue how we do it, or how we might do it better. Our future depends, of course, on what choices we arrive at, individually and collectively. And yet, most of us don't have any better strategy than picking the strongest thought that appears in our head, or our stomach, or wherever it appears, and assuming that this is our answer. Without examining where it came from, and without having the faintest clue as to HOW to think. Thinking is one subject I'm really interested in. Our ability to think abstractly is one of the key traits that define what a human is. Yet we seem to have little clue how we do it, or how we might do it better. Our future depends, of course, on what choices we arrive at, individually and collectively. And yet, most of us don't have any better strategy than picking the strongest thought that appears in our head, or our stomach, or wherever it appears, and assuming that this is our answer. Without examining where it came from, and without having the faintest clue as to HOW to think.

I got to *think* about that again, as I saw a page about Edward de Bono's latest book "Why So Stupid?" which seems to reflect just that dillemma, and apparently provide some answers. From the foreword:"Maybe we have neglected thinking. Maybe we have taken it for granted. Maybe we have believed, and still believe, that there is nothing more that can be done about thinking. We have an excellent 'thinking system' and nothing more needs to be done.

That is where I disagree. We do have an excellent thinking system - but it is inadequate. Our thinking system is all directed at the past. We recognize standard situations and provide standard answers. We have never developed the creative thinking needed to design the way forward. Our thinking is excellent for technology and almost useless in human affairs." I have several of de Bono's books, which are excellent. And yet I'm a bit suspicious about why somebody needs to write 65 books about essentially the same thing - creativity and thinking. But, whether he could really have said it all in one book, de Bono has some fine tools and insights to offer, and is an undisputed authority in that field. Here's another little tidbit from his website:"The majority of mistakes in ordinary thinking (outside technical matters) are mistakes in perception. Our traditional emphasis on logic does little for perception. If the perception is inadequate no amount of excellence in logic will make up for that deficiency.

Perception is a matter of directing attention. If you are not looking in the right direction it does not matter how clever you are, you will not see what you need to see." Right on. It doesn't matter if you eloquently and 'logically' can deduct yourself from one point to the next, if you didn't perceive what really is there, or you were looking at only a small part of it, or you were looking at the wrong thing. Most people have a certain innate sense of logic, but if the input is faulty, so is the result.

[ Patterns | 2003-04-05 22:01 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, April 1, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Seb mentions Peter Tesugen analyzing Edward de Bono's principles of simplicity, from his book "Simplicity". These are the principles: Seb mentions Peter Tesugen analyzing Edward de Bono's principles of simplicity, from his book "Simplicity". These are the principles:1. You need to put a very high value on simplicity

2. You must be determined to seek simplicity

3. You need to understand the matter very well

4. You need to design alternatives and possibilities

5. You need to challenge and discard existing elements

6. You need to be prepared to start over again

7. You need to use concepts

8. You may need to break things down into smaller units

9. You need to be prepared to trade off other things for simplicity

10. You need to know for whose sake the simplicity is being designed

Peter has a good discussion about what the less obvious points are about.

[ Patterns | 2003-04-01 00:29 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, March 8, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Here is a map of the population density on Earth. I like maps like that. I notice there's tons of space with nobody there. Because we've already turned those places into deserts mostly. And some places with a huge concentration of people. Mikel Maron says: Here is a map of the population density on Earth. I like maps like that. I notice there's tons of space with nobody there. Because we've already turned those places into deserts mostly. And some places with a huge concentration of people. Mikel Maron says:" It would be so cool to see this animated, over time. Watch the population explode and recede, like colored waves of bacteria, over centuries. This would work well for other data sets -- like the spread of memes over the world. This is something I'm tooling with -- weblogs.com + ICBM + RSS + Flash!" Yes, that would be very cool. There are lots of things I'd love to see in near real-time on a map, or a globe. I'd like to be able to play with different data sets. Resource use, money flows, health, education, net traffic, the people I know, etc.

[ Patterns | 2003-03-08 23:41 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, March 4, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

An English essay written by a teenager baffled her teacher, because she couldn't decipher what it said. It was written in text messaging short-hand, like what teenagers use to message each other on cell phones, or like what is used in fast-moving chat rooms. It started like this:"My smmr hols wr CWOT. B4, we used 2go2 NY 2C my bro, his GF & thr 3 :- kids FTF. ILNY, it's a gr8 plc." Well, that is not all that hard if you're used to seeing that kind of messages. It simply says: "My summer holidays were a complete waste of time. Before, we used to go to New York to see my brother, his girlfriend and their three screaming kids face to face. I love New York. It's a great place." Teachers and parents would typically think it is a horrible thing, that kids can't read and write in normal ways, and it means that education is going down the drain. Maybe that's what it means, and maybe it is bad. But it is also worth looking at, that what is emerging is different forms of communication, that cultivate different types of skill. To read messages like those, you're not using the same linear literary and literal skills previous generations would use. Many things are happening by pattern matching. You figure things out, not by a standard interpretation, but by looking at the whole picture and guessing at what it might mean. I notice that kids today appear to have rather advanced skills in some areas that I didn't at all have when I was a kid. My 3 year old daughter seems to learn things by some kind of pattern matching osmosis, without necessarily going through the 'logical' steps of getting there. There's a thousand channels on our cable TV, and she's not really fluent with numbers over 10, but she'll quite easily surf around between the channels she likes. Just like she can operate a web browser quite well without being able to read. It is like the new generations are evolving some skills that allow them to deal with complexity without getting confused. Because they aren't trying to reduce everything to linear logic. Maybe that is a good thing.

[ Patterns | 2003-03-04 19:37 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, February 14, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Ross Mayfield did an excellent post on Distribution of Choice and another one on Ecosystem of Networks. I was sitting looking at his neat chart, wondering why I didn't really like it very much. Well, it is a good chart, and it shows what kind of audience weblogs might have in their different roles. I guess what I don't like is that it is not how I'd *like* things to work. Which is a bit hypocritical to talk about if we're talking about emergence at the same time, and this happens to be how things emerge. But it sort of indicates that what emerges from blogs is in the bigger picture the winner-take-it-all phenomenon of power-law distributions. The people who are first or who are popular will just get more popular. Which sounds like a U.S. election to me, but it doesn't really sound like what I think emerges from blogs.

So, I decided to make my own chart, coming from a totally different place. Maybe it looks crazy to anybody but me, but, hey, I gotta try.

So, here the point is that it starts with ME and the choices I make and what happens to them. So, if we're talking about blogs, there is first whatever I have the thought of writing about. I make some choices about what to write about. Let's say we consider each of those thoughts or choices a little bubble, and that those little bubbles naturally rise up in the information ocean.

I might have a small group of people I'm already working with, and we might use blogspace as a place to work on things. We share a project, and we either put our pieces together between our blogs, or we write about what we do from each our different angles. Blogging allows us to work more openly and refer to each other's work, while also sharing it with a bigger audience.

My blogging bubbles float up and get spread wider. People I don't know read my blog, and read various people's blogs, and we get attracted to each other. Connections form. It might just be that we read each other's stuff, or we link to each other, or we start talking in other ways. That becomes a good basis for forming new groups that can act together.

All of our bubbles, mine and those from other blogs, with the added value of our collective linking choices, will float up and into the cloud of the web. Specifically they will end up in an assortment of directories and search engines, most notably in Google.

And that is in part where there are interesting and new things going on. Not just that few people get most of the attention, but also that the choices of many relatively ordinary folks become more visible than ever before. And they form emergent patterns that become very visible.

For myself and my weblog of relatively modest popularity, I notice that many of the bubbles I set up rise to considerable size and power, because they're supported by others who choose to link to them. What interests me there is not so much how great I am at showing up in search engines, but how easily the collective opinion of (a group of) bloggers will show up prominently.

A rather random example is that I wrote a couple of little blog entries about Nestle doing some not very nice things. Now, if you do a web search on CNN or on Google on "Nestle sues Ethiopia", I'm number one. If you just want to know about "Nestle Corporation", I'm number four, before several of Nestle's own sites. Nestle last year made 5.5 billion dollars in profits, but yet you and I, by linking a bit to each other's posts, can compete very well with their web presence and influence public opinion. Not me, but us. It wasn't even my own info I posted.

The point is not at all whether I have unfairly more or less readers than some other weblog. The emerging democracy in blogs is in that we together leverage our choices in a way that normally isn't possible unless you run a big corporation or you're run by one. We're a swarm of thought bubbles.

[ Patterns | 2003-02-14 04:28 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, February 9, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

Doc Searls invented BuzzPhraser, the TechnoLatin phrase generator. It is great for coming up with impressively sounding buzz phrases to use in your next business plan. I bet investment funds are readily available for the..Inherently Bridging Exclusive Quality Proposition Channel particularly when it comes with the.. Upwardly Configured Interactive Paradigm Empowerment Option but of course, first you need to make the..Operationally Value-Added Movement Differentiation Decision

[ Patterns | 2003-02-09 17:31 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, January 23, 2003 |  |

|

|

|

James Carse makes some very interesting distinctions between what is a society and what is a culture in his book "Finite and Infinite Games" [which I mentioned here]. James Carse makes some very interesting distinctions between what is a society and what is a culture in his book "Finite and Infinite Games" [which I mentioned here]."In their own political engagements infinite players make a distinction between society and culture. Society they understand as the sum of those relations that are under some form of public constraint, culture as whatever we do with each other by undirected choice." Society consists of what people do because of necessity, because they HAVE to. Society is a finite game with certain rules that have to be adhered to. Society will perpetuate rules from the past and will resist any changing of the rules. Society has a lot to do with achieving and maintaining power, largely based on the games one has won in the past and the status one has achieved from that.

A society is bounded temporarily and spatially. There is a start and an end to a society, and it will defend its borders and its definition vehemently. Members of a society are only those who live within its boundaries and agree to the validity of its rules.

A culture, on the other hand, is not bounded. Anybody at any time anywhere can participate in a culture.

[ Patterns | 2003-01-23 23:45 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

<< Newer stories Page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Older stories >> |