| Sunday, November 1, 2009 |  |

|

|

|

That's in New Scientists. I'm glad there are questions that keep physicists up at night. That means that there are people doing science, of course, rather than just sticking with what they think they know. This is one of the questions: What is reality really?

The material world may, at some level, lie beyond comprehension, but Anton Zeilinger, professor of physics at the University of Vienna, is profoundly hopeful that physicists have merely scratched the surface of something much bigger. Zeilinger specialises in quantum experiments that demonstrate the apparent influence of observers in the shaping of reality. "Maybe the real breakthrough will come when we start to realise the connections between reality, knowledge and our actions," he says. The concept is mind-bending, but it is well established in practice. Zeilinger and others have shown that particles that are widely separated can somehow have quantum states that are linked, so that observing one affects the outcome of the other. No one has yet fathomed how the universe seems to know when it is being watched...

[ Science | 2009-11-01 16:35 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, October 14, 2008 |  |

|

|

|

CNN: City hopes to shuttle people in futuristic 'podcars' CNN: City hopes to shuttle people in futuristic 'podcars' Unlike mass transit, podcars carry two to 10 passengers, giving travelers the freedom and privacy of their own car while reducing the use of fossil fuels, reducing traffic congestion and freeing up space now monopolized by parking.

At stations located every block or every half-mile, depending on the need, a rider enters a destination on a computerized pad, and a car would take the person nonstop to the location. Stations would have slanted pull-in bays so that some cars could stop for passengers, while others could continue unimpeded on the main course.

"It works almost like an elevator, but horizontally," said Roberts, adding podcar travel would be safer than automobile travel.

The podcar is not entirely new. A limited version with larger cars carrying up to 15 passengers was built in 1975 in Morgantown, West Virginia, and still transports West Virginia University students.

Next year, Heathrow Airport outside London will unveil a pilot podcar system to ferry air travelers on the ground. Companies in Sweden, Poland and Korea are already operating full-scale test tracks to demonstrate the feasibility. Designers are planning a podcar network for Masdar City, outside Abu Dhabi, which is being built as the world's first zero-carbon, zero-waste city.

Meanwhile, more than a dozen cities in Sweden are planning podcar systems as part of the country's commitment to be fossil-fuel-free by 2020, said Hans Lindqvist, a councilman from Varmdo, Sweden, and chairman of Kompass, an association of groups and municipalities behind the Swedish initiative.

"Today's transportation system is reaching a dead end," said Lindqvist, a former member of the European parliament.... Yeah, sounds great. But "not entirely new" is a bit of an understatement. I feel cheated. Where's my future?

When I was a kid, in the 60s, my mother subscribed to a popular science magazine called "Vor Viden" (Danish for "Our Knowledge"). Which every month was chock-full of exiting technological marvels that were just around the corner. Like, exactly this pod car scenario. According to that magazine, there had already been test tracks constructed in Germany and other places, and there were photos, which looked very much like these photos. It all sounded very promising, like it would be coming to my neighborhood in a few years. But we're talking about the mid 60s. 40 years ago. It obviously didn't happen so far, and maybe you can understand if I'm a bit skeptical when I read almost the exact same article four decades later, and I'm supposed to believe it.

I'd like to believe. But there were also functioning flying cars in the 1960s. And amphibian cars. And we went to the moon in the 1960s. And to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. I'd have expected that we would have gotten a bit further along those lines since then, but it hasn't been much.

But we have color TV. Oh, and the internet and mobile phones. Some things are actually better than predicted in the popular science magazines of the 60s.

But it is a little silly and unexpected that we're still driving cars with motors that run on exploding fossils. And that we sit and push pedals and turn steering wheels. Seems a bit like the Flintstones, which incidentally was one of my favorite TV program in the 60s. I had just hoped for the Jetsons.

[ Science | 2008-10-14 20:33 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, July 5, 2008 |  |

|

|

|

Self-Organized Criticality (SOC) is a theory about some principles that seem to pervade nature and which seems to explain various kinds of complexity very well. One of the most clear explanations is found in the book How Nature Works, by Per Bak, a Danish theoretical physicist who had an important role in developing the theory. Self-Organized Criticality (SOC) is a theory about some principles that seem to pervade nature and which seems to explain various kinds of complexity very well. One of the most clear explanations is found in the book How Nature Works, by Per Bak, a Danish theoretical physicist who had an important role in developing the theory.

SOC has been applied within a great number of disciplines, but it seems to remain a controversial subject for many scientists. You can guess that from looking at the reviews on Amazon for the book I just mentioned. Half the people absolutely love it, and the other half are bending over backwards to try to discredit it. It is indeed terribly ambitious to try to present a principle that covers so many natural phenomena. The mere attempt of doing so will rub anybody the wrong way who favors reductionism, i.e. reducing the world to smaller pieces that follow clearly defined laws that can be observed repetitively in clearly defined ways. Could of course also be bacause Bak was a pretty obnoxious character who didn't hesititate to tell other scientists off.

Self-Organized Criticality says basically that there are certain dynamic systems that have a critical point as an attractor. I.e. that they "by themselves" will move towards a critical state. There are certain characteristics to such a system, but more about that in a moment.

[ Science | 2008-07-05 00:08 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, May 16, 2008 |  |

|

|

|

How wonderful. Stuart Kauffman, theoretical biologist and complexity theory pioneer, talks about reinventing the sacred, getting over reductionism, appreciating the awesome wonder of existence, and redefining God to be essentially the creativity of the universe. You just can't explain the complexity of the universe by reducing it all to physics that all were pre-determined. There's an article in New Scientist: "Why humanity needs a God of creativity", there's his excellent entry at Edge: "Beyond Reductionism", and there's his latest book "Reinventing the Sacred". How wonderful. Stuart Kauffman, theoretical biologist and complexity theory pioneer, talks about reinventing the sacred, getting over reductionism, appreciating the awesome wonder of existence, and redefining God to be essentially the creativity of the universe. You just can't explain the complexity of the universe by reducing it all to physics that all were pre-determined. There's an article in New Scientist: "Why humanity needs a God of creativity", there's his excellent entry at Edge: "Beyond Reductionism", and there's his latest book "Reinventing the Sacred". [T]he unfolding of the universe - biotic, and perhaps abiotic too - appears to be partially beyond natural law. In its place is a ceaseless creativity, with no supernatural creator. If, as a result of this creativity, we cannot know what will happen, then reason, the Enlightenment's highest human virtue, is an insufficient guide to living our lives. We must use reason, emotion, intuition, all that our evolution has brought us. But that means understanding our full humanity: we need Einstein and Shakespeare in the same room.

“Reason is an insufficient guide to living our lives: put Einstein and Shakespeare in the same room”

Shall we use the "God" word? We do not have to, yet it is still our most powerful invented symbol. Our sense of God has evolved from Yahweh in the desert some 4500 years ago, a jealous, law-giving warrior God, to the God of love that Jesus taught. How many versions have people worshipped in the past 100,000 years?

Yet what is more awesome: to believe that God created everything in six days, or to believe that the biosphere came into being on its own, with no creator, and partially lawlessly? I find the latter proposition so stunning, so worthy of awe and respect, that I am happy to accept this natural creativity in the universe as a reinvention of "God". From it, we can build a sense of the sacred that encompasses all life and the planet itself. From it, we can change our value system across the globe and try, together, to ease the fears of religious fundamentalists with a safe, sacred space we can share. And from it we can, if we are wise, find means to avert wars of civilisations, the ravages of global warming, and the potential disaster of peak oil. The EDGE article is dense with science, and I understand less than half of it, but very worth reading, even if you don't get it all. So I'm just quoting the easy-to-read conclusions. Remember, this is a hard-core scientist here, not just somebody who writes popular books that involve scientific metaphors. To ever succeed, this new view needs to be soft spoken. You see, we can say, here is reality, is it not worthy of stunned wonder? What more could we want of a God? Yes, we give up a God who intervenes on our behalf. We give up heaven and hell. But we gain ourselves, responsibility, and maturity of spirit. I know that saying that ethics derives from evolution undercuts the authority of God as its source. But do we need such a God now? I think not. Nor do we need the spiritual wasteland that post-modernism has brought us. Beyond my admired friend Kenneth Arrow, natural parks are valuable because life is valuable on its own, a wonder of emergence, evolution and creativity. Reality is truly stunning. So if you find this useful, let us go forth, as was said long ago, and invite consideration by others of this new vision of reality. With it, let us recreate spiritual community and membership. Let us go forth. Civilization needs to be changed. Count me in.

(Via BoingBoing)

[ Science | 2008-05-16 13:34 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, January 11, 2008 |  |

|

|

|

Ha, this is great. Richard Dawkins meets Rupert Sheldrake. We could say that this is about what happens when a scientist meets an... uhm.... charlatan. You can decide for yourself which is which. This account by Sheldrake was published in "Network Review: The Journal of the Scientific and Medical Network".Richard Dawkins is a man with a mission – the eradication of religion and superstition, and their total replacement with science and reason. Channel 4 TV has repeatedly provided him with a pulpit. His two-part polemic in August 2007, called Enemies of Reason, was a sequel to his 2006 diatribe against religion, The Root of All Evil?

Soon before Enemies of Reason was filmed, the production company, IWC Media, told me that Richard Dawkins wanted to visit me to discuss my research on unexplained abilities of people and animals. I was reluctant to take part, but the company’s representative assured me that “this documentary, at Channel 4’s insistence, will be an entirely more balanced affair than The Root of All Evil was.” She added, “We are very keen for it to be a discussion between two scientists, about scientific modes of enquiry”. So I agreed and we fixed a date.

I was still not sure what to expect. Was Richard Dawkins going to be dogmatic, with a mental firewall that blocked out any evidence that went against his beliefs? Or would he be open-minded, and fun to talk to?

The Director asked us to stand facing each other; we were filmed with a hand-held camera. Richard began by saying that he thought we probably agreed about many things, “But what worries me about you is that you are prepared to believe almost anything. Science should be based on the minimum number of beliefs.”

I agreed that we had a lot in common, “But what worries me about you is that you come across as dogmatic, giving people a bad impression of science.”

He then said that in a romantic spirit he himself would like to believe in telepathy, but there just wasn’t any evidence for it. He dismissed all research on the subject out of hand. He compared the lack of acceptance of telepathy by scientists such as himself with the way in which the echo-location system had been discovered in bats, followed by its rapid acceptance within the scientific community in the 1940s. In fact, as I later discovered, Lazzaro Spallanzani had shown in 1793 that bats rely on hearing to find their way around, but sceptical opponents dismissed his experiments as flawed, and helped set back research for well over a century. However, Richard recognized that telepathy posed a more radical challenge than echo-location. He said that if it really occurred, it would “turn the laws of physics upside down,” and added, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

“This depends on what you regard as extraordinary”, I replied. “Most people say they have experienced telepathy, especially in connection with telephone calls. In that sense, telepathy is ordinary. The claim that most people are deluded about their own experience is extraordinary. Where is the extraordinary evidence for that?”

He [didn't] produce any evidence at all, apart from generic arguments about the fallibility of human judgment. He assumed that people want to believe in “the paranormal” because of wishful thinking.

We then agreed that controlled experiments were necessary. I said that this was why I had actually been doing such experiments, including tests to find out if people really could tell who was calling them on the telephone when the caller was selected at random. The results were far above the chance level.

The previous week I had sent Richard copies of some of my papers, published in peer-reviewed journals, so that he could look at the data.

Richard seemed uneasy and said, “I don’t want to discuss evidence”. “Why not?” I asked. “There isn’t time. It’s too complicated. And that’s not what this programme is about.” The camera stopped.

The Director, Russell Barnes, confirmed that he too was not interested in evidence. The film he was making was another Dawkins polemic.

I said to Russell, “If you’re treating telepathy as an irrational belief, surely evidence about whether it exists or not is essential for the discussion. If telepathy occurs, it’s not irrational to believe in it. I thought that’s what we were going to talk about. I made it clear from the outset that I wasn’t interested in taking part in another low grade debunking exercise.”

Richard said, “It’s not a low grade debunking exercise; it’s a high grade debunking exercise.”

In that case, I replied, there had been a serious misunderstanding, because I had been led to believe that this was to be a balanced scientific discussion about evidence. Russell Barnes asked to see the emails I had received from his assistant. He read them with obvious dismay, and said the assurances she had given me were wrong. The team packed up and left.

Richard Dawkins has long proclaimed his conviction that “The paranormal is bunk. Those who try to sell it to us are fakes and charlatans”. Enemies of Reason was intended to popularize this belief. But does his crusade really promote “the public understanding of science,” of which he is the professor at Oxford? Should science be a vehicle of prejudice, a kind of fundamentalist belief-system? Or should it be a method of enquiry into the unknown?

[ Science | 2008-01-11 19:00 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Sunday, December 2, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

According to Telegraph, a poor surfer dude physicist has come up with a theory of everything that has everybody talking. According to Telegraph, a poor surfer dude physicist has come up with a theory of everything that has everybody talking.The new theory reported today in New Scientist has been laid out in an online paper entitled "An Exceptionally Simple Theory of Everything" by Lisi, who completed his doctorate in theoretical physics in 1999 at the University of California, San Diego.

He has high hopes that his new theory could provide what he says is a "radical new explanation" for the three decade old Standard Model, which weaves together three of the four fundamental forces of nature: the electromagnetic force; the strong force, which binds quarks together in atomic nuclei; and the weak force, which controls radioactive decay.

The reason for the excitement is that Lisi's model also takes account of gravity, a force that has only successfully been included by a rival and highly fashionable idea called string theory, one that proposes particles are made up of minute strings, which is highly complex and elegant but has lacked predictions by which to do experiments to see if it works.

But some are taking a cooler view. Prof Marcus du Sautoy, of Oxford University and author of Finding Moonshine, told the Telegraph: "The proposal in this paper looks a long shot and there seem to be a lot things still to fill in."

And a colleague Eric Weinstein in America added: "Lisi seems like a hell of a guy. I'd love to meet him. But my friend Lee Smolin is betting on a very very long shot."

Lisi's inspiration lies in the most elegant and intricate shape known to mathematics, called E8 - a complex, eight-dimensional mathematical pattern with 248 points first found in 1887, but only fully understood by mathematicians this year after workings, that, if written out in tiny print, would cover an area the size of Manhattan. Read about the E8 at Wikipedia. And then explain it to me once you get it.

[ Science | 2007-12-02 21:10 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, September 27, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

Doesn't really say much, but that's good news. Breibart:Parallel universes really do exist, according to a mathematical discovery by Oxford scientists described by one expert as "one of the most important developments in the history of science".

The parallel universe theory, first proposed in 1950 by the US physicist Hugh Everett, helps explain mysteries of quantum mechanics that have baffled scientists for decades, it is claimed.

In Everett's "many worlds" universe, every time a new physical possibility is explored, the universe splits. Given a number of possible alternative outcomes, each one is played out - in its own universe.

A motorist who has a near miss, for instance, might feel relieved at his lucky escape. But in a parallel universe, another version of the same driver will have been killed. Yet another universe will see the motorist recover after treatment in hospital. The number of alternative scenarios is endless.

It is a bizarre idea which has been dismissed as fanciful by many experts. But the new research from Oxford shows that it offers a mathematical answer to quantum conundrums that cannot be dismissed lightly - and suggests that Dr Everett, who was a Phd student at Princeton University when he came up with the theory, was on the right track.

Commenting in New Scientist magazine, Dr Andy Albrecht, a physicist at the University of California at Davis, said: "This work will go down as one of the most important developments in the history of science." Actually it doesn't tell us anything about what they figured out. But there is a parallel universe somewhere, in which that would have been a more informative article. And there's another one where I would have been able to understand the math in that more informative article.

Now, the next question is: Does the universe split all the time, in all possible directions, or only on special occasions, like just before you buy lottery tickets, or when you're leaning out the window in a tall building? I'd say it does it all the time, but that the idea of "splitting" gives the completely wrong idea. It is just a matter of having enough dimensions. Does the North/South compass direction split into East or West in millions of places? That's an equally silly question. If you're walking North, you're free to stop at any time and walk East, and you're free to walk back and go SouthWest. The place you came from didn't disappear just because you left it. That's the magic of being able to move in two dimensions. Parallel universes is just the same kind of thing, and only sounds magical because we folks are dimensionally challenged. We think we're walking in just one direction, even though we're changing tracks all the time. And of course there are multiple choices of tracks in a great many places. Whether there's somebody who took all the possible paths is, I think, a question that math alone will not solve. The universe doesn't need to split, because it has plenty of dimensions. But what about you - do you split?

[ Science | 2007-09-27 00:46 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, July 5, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

An article at Nature Physics. One can only see it if one pays, but this is the abstract.Was the Universe before the Big Bang of classical nature, described well by a smooth space–time? Or was it in a highly fluctuating quantum state? This is one of the most basic questions that we may ask once it is accepted that there was something before the Big Bang. Loop quantum gravity applied to isotropic models has shown that the quantum evolution of a wavefunction extends through the Big Bang. Although a general demonstration is still lacking, this may suggest that calculations, and possibly future indirect observations, may allow us to see the Universe as it was before the Big Bang. Here, we analyse an explicit model with a pre-Big Bang era, indicating limitations that would imply that it is practically impossible to answer some of our questions. Assumptions (or prejudice) will remain necessary for knowing the precise state of the Universe, which cannot be fully justified within science itself. I suspect I wouldn't understand it, even if I read the whole thing, so that's about enough. But the interesting thought there is the prospect of modeling what happened before the Big Bang. Would be fun if we had some new time coordinates, just as A.D. and B.C., so how about B.B.B. for Before Big Bang, and A.B.B. for After Big Bang, of course. Big Bada Boom.

[ Science | 2007-07-05 23:40 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, June 27, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

Wikipedia: Wikipedia: Naïve realism is a common sense theory of perception. Most people, until they start reflecting philosophically, are naïve realists. This theory is also known as "direct realism" or "common sense realism".

Naïve realism claims that the world is pretty much as common sense would have it. All objects are composed of matter, they occupy space, and have properties such as size, shape, texture, smell, taste and colour. These properties are usually perceived correctly. So, when we look at and touch things we see and feel those things directly, and so perceive them as they really are. Objects continue to obey the laws of physics and retain all their properties whether or not there is anyone present to observe them doing so.

Naïve realism is distinct from scientific realism. Scientific realism says the universe really contains just those properties which feature in a scientific description of it, and so does not contain properties like colour per se, but merely objects that reflect certain wavelengths owing to their microscopic surface texture. The naïve realist, on the other hand, would say that objects really do possess the colours we perceive them to have. Thanks, Anandavala for mentioning it in your article The Scientific Case Against Materialism. The Wikipedia entry tries to imply that it is something that kind of doesn't apply to scientists, which of course isn't quite so. Actually the odd statement there that "the universe really contains just those properties which feature in a scientific description of it" hints at where scientific thinking can get off track, but maybe there's another name for that. You know, the idea that reality is what is found in sufficiently agreed-upon scientific theories, rather than what it really is, beyond any kind of theory.

You'll also find an oddly large percentage of those people who claim science as the foundation of their thinking who mostly argue for what science used to be. You know, aristotelean and newtonian kind of science. Which involves a certain kind of naïve realism, at least in comparison with more modern stuff. I mean, that the universe consists of seperate objects that have properties like mass and that are subject to gravity. Oh, that's how it appears on a superficial and tangible level, and that's practical for building houses, and satellites, and for maintaining your household in a sane way. But in terms of how it really is, it seems to me that science has been beyond that for a century or so. But a lot of us haven't really internalized stuff like quantum physics and even relativity theory, because it is odd and counter-intuitive. Because it doesn't fit with our naïve kind of observation of what is there. So we easily default to arguing that all the odd stuff is impossible, part of some kind of organized scam, or at best an unproven theory.

OK, I often complain about this kind of thing. It is one of my pet issues. And "Science and Sanity" is still on my list of all time most important books written. It is important not to forget that your simplified idea about reality is not reality, no matter who agrees with you. The foundation of sanity is to stay aware of the difference between perceptions of stuff and the real stuff.

Here's another article that Anandavala links to:The first stop on our tour is a place called "naive realism." Naive realism is a way of looking at the world. Ways of looking at the world are sometimes dressed up with the word "philosophy," but I won't split a hair's difference.

True naive realists would never sum up or analyze their views, because they do not consider them views but the way things obviously are. However, I will do my best to illuminate them:

"I, the naive realist, am a human being. There is this one physical world, the space where everything exists and the time in which everything happens. There are many things in this physical world, each largely separate from the other and persisting over a span of time. Time is divided into 'now,' which is real and experienced, 'the past,' which once existed but now does not, and 'the future,' which does not exist yet but will.

"My senses give me direct knowledge of reality. If I see a chair, it is because there is a chair physically where and when I see it. There are exceptions, like when I am dreaming or watching a movie, but these are rare and obviously not real.

"I can know things through my senses, through thinking about things, and through communication with other people. Other people's beliefs may be correct or not, but beliefs of people I respect, and beliefs held commonly by most people in my society, are usually true."

Naive realism sounds reasonable enough, but it can lead to science, which as we shall see, contradicts naive realism on nearly every account. I hope so, but that's where I'm skeptical. Real science, yeah. But there's the widespread belief system, sometimes called materialism, which tends to trump science if one doesn't watch it. I.e. that the world is fundamentally the world of physical objects we see, and nothing that isn't material could possibly exist, and anything else that appears to exist can only come from matter, and no other explanation is possible and even worth considering. You know, naïve materialism. Accepting things without considering the alternatives and without verification.

[ Science | 2007-06-27 00:58 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, May 26, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

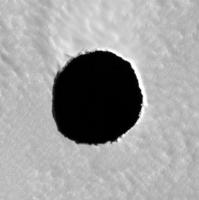

Closeup of one of several likely openings into recently dicovered underground caverns on Mars. This one is 100 meters wide. Closeup of one of several likely openings into recently dicovered underground caverns on Mars. This one is 100 meters wide.At its highest resolution of 25 centimeters per pixel, the HiRISE camera can see the detailed shape of the slightly scalloped edge of a hole on the flank of Mars' Arsia Mons (left), but no amount of image enhancement (right) can bring out any further details inside the hole. That means that the walls of the cave are overhanging -- the cave is larger below the ground than the entrance we can see at the surface -- and that it is very deep. Mars' dusty atmosphere produces enough scattered light that "skylight" would illuminate the floor of a shallow cavern well enough for HiRISE to detect it.

The hope for the HiRISE images was that we could see some details from inside the hole. But as you can see by the highly stretched version at right, there is absolutely nothing visible inside that hole. It's black black black black black. HiRISE is a very sensitive instrument, and Mars' dusty atmosphere scatters quite a bit of light around, so there is certainly light entering that cave hole and bouncing around the interior. But it seems that the cave is so big and so deep that almost none of the light that enters the cave comes out. It's deep, and it's big; the hole that we see really is just a skylight on a big subterranean room. How big? We'll never know for sure without visiting it, but I expect that Cushing and his coauthors and the HiRISE team will be crunching the numbers on the illumination conditions and the sensitivity of the camera to put a lower limit on how deep that cave must be for HiRISE to be able to see nothing at all inside it.

Think about that. All these orbiters at Mars, and most of them are just seeing the surface and atmosphere. To be sure, there are two instruments up there -- MARSIS on Mars Express and SHARAD on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter -- that are probing the shape of the subsurface with ground-penetrating radar. But neither of those instruments have the resolution necessary to tell us what the inside of this cave looks like. It might as well be in the greatest depths of space. Here there be dragons. What's down there? Are there stalactites and stalagmites and crystals, or is it just a vast open room or tunnel? Yeah, might just be something boring, like a parking garage.

[ Science | 2007-05-26 02:26 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, April 25, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

PhysicsWeb. I'm not sure I understand it well, but the scientific discussion seems to be on whether there are hidden variables in the universe that make reality exist in a consistent way, even when nobody's looking at it. And whether the universe is basically local or non-local. "Local" would mean that one can separate events completely from each other, so that they can't instantenously influence other events.Markus Aspelmeyer, Anton Zeilinger and colleagues from the University of Vienna, however, have now shown that realism is more of a problem than locality in the quantum world. They devised an experiment that violates a different inequality proposed by physicist Anthony Leggett in 2003 that relies only on realism, and relaxes the reliance on locality. To do this, rather than taking measurements along just one plane of polarization, the Austrian team took measurements in additional, perpendicular planes to check for elliptical polarization.

They found that, just as in the realizations of Bell's thought experiment, Leggett's inequality is violated – thus stressing the quantum-mechanical assertion that reality does not exist when we're not observing it. "Our study shows that 'just' giving up the concept of locality would not be enough to obtain a more complete description of quantum mechanics," Aspelmeyer told Physics Web. "You would also have to give up certain intuitive features of realism." Sounds like they're saying that experiements really do confirm that reality isn't real unless somebody's looking at it, and that everything is instantanously connected with everything else, so you can't isolate any piece of anything and claim that it has a real existence, separate from everything else, and seperate from who's observing it. I sort of figured as much, but it sounds good if they're rocking the boat a bit by proving it.

[ Science | 2007-04-25 14:17 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, March 31, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

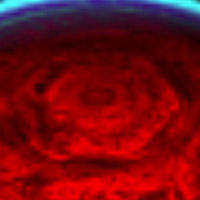

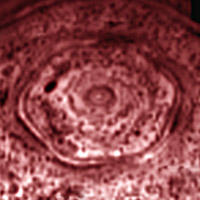

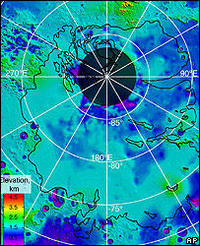

Strange indeed. A giant hexagon on Saturn's north pole. 25,000 km wide, 60 km deep. Bigger than the red spot on Jupiter. And it seems to be stable, since it was first spotted by Voyager 26 years ago. Nobody seems to be able to explain how it can be hexagonal of all things, with almost regular even sides. I think it is that big bolt you see in the middle, which holds the planet's axis together. Or maybe it is the headquarters of the defense department for the Saturnians.

[ Science | 2007-03-31 00:19 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, March 22, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

National Science Foundation: National Science Foundation:Ever since 1887, when Norwegian mathematician Sophus Lie discovered the mathematical group called E8, researchers have been trying to understand the extraordinarily complex object described by a numerical matrix of more than 400,000 rows and columns.

Now, an international team of experts using powerful computers and programming techniques has mapped E8--a feat numerically akin to the mapping of the human genome--allowing for breakthroughs in a wide range of problems in geometry, number theory and the physics of string theory. You can read about it in Wikipedia. I don't really understand a word of it. It has a lot of dimensions, but I don't get whether it is 8 or 57 or 248, but it is obviously very complex. And somehow important to string theory and other fields. So, good job, I guess. I can't wait for the origami version.

[ Science | 2007-03-22 16:53 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, March 17, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

That's fun news. Caves on Mars. That's fun news. Caves on Mars. The caves may be the only natural structures capable of protecting primitive life forms from micrometeoroids, UV radiation, solar flares and high energy particles that bombard the planet's surface.

The spacecraft spotted what seemed to be vertical "skylight" entrances to caves below the surface.

There is a sheer drop of between about 80m and 130m or more to the cave floors below.

During the day, one of the features - nicknamed "Annie" - is warmer than surrounding pits and cooler than sunlit areas.

Night time temperatures are warmer than nearly all surrounding areas.

Co-author Glen Cushing, from the US Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Arizona, said this was exactly what would be expected if the feature were a cave. And, on top of that, they've also discovered huge ice deposits on the south pole of Mars. Up to 2.3 miles thick. Enough water to cover the whole planet with 36 feet of water, if it melted. ... Of course, that would flood the caves too.

[ Science | 2007-03-17 16:20 | 0 comments | PermaLink ]

|

|

| Thursday, March 15, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

Researchers studying laughter say that.. Researchers studying laughter say that..It's an instinctual survival tool for social animals, not an intellectual response to wit. It's not about getting the joke. It's about getting along. It's a way to make friends and also make clear who belongs where in the status hierarchy. What I think is funny is the thought of serious scientists in lab coats wracking their brains to try to make sense out of laughter.

Are they right? Hm, I don't know. One can very well laugh for no reason at all. That's an old sort of meditation technique, for that matter. But that doesn't mean it is just a social thing.

What is humor? I'd say it is when one notices something that is off, out of place, and one notices it within a certain rhythm where it produces a freeing up of ... something ... emotional energy, I suppose we could say. It is not mental per se, but it does have something to do with perception, how one sees and experiences things. A joke is not per definition funny or not. All depends on the circumstances and the rhythm of delivery, and whether there's something that gets liberated from it. And something can well be liberated without any particular logical reason.

It is when you see the sillyness of reality, any kind of reality, imagined or not. It is when you look through the world and realize that it isn't really as serious and coherent as it pretends to be. It is a joke. It is a bit of enlightenment to notice that. Might have nothing directly to do with what somebody just said.

But just about getting along? I don't think I buy that. Why would one laugh alone, then?

[ Science | 2007-03-15 01:47 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Slashdot on a speech by Stephen Hawking a few days ago: Slashdot on a speech by Stephen Hawking a few days ago:Speaking to a sold out crowd at the Berkeley Physics Oppenheimer Lecture, Hawking said yesterday that he now believes the universe spontaneously popped into existence from nothing. He said more work is needed to prove this but we have time because 'Eternity is a very long time, especially towards the end.' Uhm, yeah, but it sort of goes faster in the middle. And who doesn't love spontaneous popping-into-existence.

[ Science | 2007-03-15 01:04 | 0 comments | PermaLink ]

|

|

| Monday, February 19, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

Slashdot: Slashdot:"The Fermi paradox says that if extraterrestrial civilizations exist, at least one of them should have colonized the entire galaxy by now. But since there is no evidence of this, humankind must be the only intelligent life in the galaxy. The Space Review has an article on how the Fermi paradox can be applied to human civilization. It says that, like the extraterrestrials, humans have three choices: colonize the galaxy, remain on Earth, or become extinct." And the conclusion is pretty much that if nobody else seems to be colonizing the galaxy, we've got to do it. Which is of course fun to think about.

But I wanted to comment on that whole idea that if extraterrestrials existed, they'd inevitably have colonized the galaxy, and we'd have met them, and since we don't see them, they don't exist. It seems to be a pretty prevalent view amongst science-buffs.The Fermi paradox is the apparent contradiction between high estimates of the probability of the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations and the lack of evidence of contact with such civilizations. The problem is that it all assumes that extraterrestrials would be very much like us, and they'd be doing the same kinds of things we could imagine doing right now, and they live in a universe that's based on the theories we've come up with so far.

But this is all very iffy. Sure, if the universe really is as mechanical as we imagine, and if the only thing these guys could do would be to send radio signals, and send up rockets, and then make better rockets, and after a few centuries send out inter-stellar rockets, yeah, then we'd be able to watch their TV shows, and some space probes ought to have passed by.

But if reality really is constructed radically differently, maybe not. Imagine for one thing if we live in a 3 dimensional reality, what if most everybody else live in a 4 or 5 dimensional reality. Would they bother giving us signals we can recognize on our terms? There are plenty of anthills on our planet, but have we ever bothered to send in a representative of our civilization that would talk with one of them on their terms? Maybe a little ant that would walk in, and wave his antennas and try to say that we come in peace, and there's a big world beyond their anthill. We haven't bothered, because it didn't seem worth the trouble, and ants aren't all that smart anyway. What were we gonna talk about? Uhm, there's food over there! And they're probably just going to kill our representative. Who says we don't seem the same to a suitably advanced alien race. Kind of retarded folks living in our own little world.

And we assume that there's sort of limited space that we all share. Even though the galaxy is big, we'd guess that if there's intelligent beings on some planet circling some other star, they'd think of colonizing the galaxy, and its the same galaxy we're in. That's a mechanical view of how reality works, which might not check out.

Imagine that maybe we're living in more like a virtual reality. What we see is stretching billions of light years in all directions, but what if it still is just basically our own virtual reality projection, corresponding with how we look at the world right now. And all these other guys might not have exactly the same virtual reality to operate in, because their world view is different.

Think of the way we can construct virtual worlds right now, on the Internet. There's a server, or a bunch of servers, rather, where World of Warcraft is simulated, and lots of people can go and log in and live in that. And there are some other servers that house Second Life, and one can go live there. The rules are different between them, and they're different spaces. If you walk to the edge of the Warcraft world, you're not going to see the Second Life world. Doesn't matter if you get an extra large telescope or something, because it isn't there. Even if the servers were in the same datacenter, you could not see one from the other, because that's not how the simulation is done. Somebody could very well make an interface, like a phonebooth from which you could teleport from one to the other, but if they don't, there's no way of getting from one to the other, other than logging out altogether, and logging into the other. And say one group in World of Warcraft decided to colonize all of the known universe, they could go and do so without ever running into any aliens. They'd find nothing but other World of Warcraft players, no matter how far they walk in any direction. And if some of these guys had forgotten that they were just humans who logged in from home, and they tried to reason things out from inside the game, they might well conclude that this is all that exists, and there's no other kind of virtual worlds, and no other kinds of people. Which would be all false, of course.

You can't necessarily make sense of a problem when you're inside of the problem. You can't solve a problem with the thinking that created it, as Einstein said. If you live inside a certain illusion, you can't necessarily transcend the illusion, using only pieces of that same illusion.

When some civilization is expanding, even greatly, there's not necessarily any reason they should run into every other civilization. Particularly if we're talking about 3 or 4 dimensional civilizations in a universe with more dimensions. There's plenty of room for everybody.

Say you do want to contact some other world, maybe the way of doing that is something totally different than just travelling far in your own world.

Imagine curved space. 3D space can easily be curved so that when you travel far in one direction, you'll end up where you started. It might be arbitrarily big, but still limited. That's what you see, for example, with a sphere. 2D Flatlanders could live on the surface of a sphere, and if they go far enough in one direction, they come back to where they started, from the opposite direction. Which would seem very puzzling to them, as the world obviously is flat. But for us with a 3D vantage point, it is perfectly obvious, that their plane is curved. No big reason to not think the same applies to us. Even if we can see billions of lightyears away, the space might just curve around, and the whole universe might just be one little bubble of reality. Of which there might be many more.

That you don't see anybody else in your own little bubble says absolutely nothing about whether there is somebody else in other bubbles. But if we wanted to contact them, we'd need to do something more than just walking around in our own sandbox. We'd need to create a bridge of some kind. We'd need to come up with some construct in our reality that can interface with a construct in another reality.

If a reality is a self-contained simulation, with its own objects, rules, players, etc, then it would be natural enough that you can't just violate its rules by throwing in a alien element. Like, again, if I want to meet somebody in Second Life, I have to play by the Second Life rules. I can't walk in there in my physical body, obviously. I couldn't walk in there as a World of Warcraft avatar either. I could probably construct something similar in Second Life, and I could maybe create an interface between the two. Like, I could be wearing some kind of body suit that mapped my movements to those of the Second Life avatar I had constructed. But I have to play by the rules.

Imagine that it works in a similar fashion in our physical reality. An alien can't just walk in and play by totally different rules. If he wanted to get into our reality, he'd have to find out how to log into it, how to choose a suitable representation of himself, and how to play by the rules. And if we follow the video game metaphor, it doesn't matter what kind of absurd powers you have in real life, if you want to play in the game, your only option is to use the tools available to do so, which per definition would follow the rules that create the simulation. It doesn't matter if I'm Donald Trump and I yell at people on the phone, I simply just can't drive my car into Second Life. Oh, I can pay somebody to create a simulation of my car in Second Life, and then I can operate that with the mouse of my computer. But the real car, no.

Makes sense? So, if some extraterrestrials really want to talk to us, what would they appear as? If the rules of our simulation allowed landing spacecraft and alien blob creatures, that could work. But it wouldn't necessarily be the REAL alien creatures in their real spaceships you'll see, just like it isn't the real you I see in Second Life. And if they'd have to pick some avatar anyway, they might as well pick an avatar that we find normal. Like, uhm, regular human beings who drive in cars and eat cheerios and go to work. That seems to be a reality we humans can understand. So, if you wanted to interact with us, you might get further with that than with trying to land a 50 mile long trans-dimensional light-craft on the White House lawn. That would get our attention alright, but it would change our civilization irretrievably at the same time, so it wouldn't be a very gentle way of communicating. So, maybe better being a human, driving a car. Or you might try some more artistic, surreal stuff, like crop circles. Or maybe a few scattered appearances of strange flying craft, to gauge our response, but always making sure they only appear on really fuzzy pictures, and only seen at a distance by groups of not too reliable witnesses.

So, I'm saying that just because aliens exist, it doesn't mean they sort of randomly come by on their way somewhere else. If they come by, it might be because they particularly have decided to interact with us, or to study us, and they particularly need to log in to our reality. And if they do, they'll probably read the user manual first.

What I'm touching on is a view of reality where reality is a simulation created by individual or collective worldviews. We here on this planet obviously share a certain reality, and we can interact with each other within it. But if we want to interact with drastically different realities, or beings in those realities want to interact with us, we might both need to transcend our game rules a bit, and find some common ground.

So, should we go and colonize the galaxy? Yeah, why not. But if we want to meet some other interesting people, we might have to come up with something different than just sending pieces of metal lightyears away. We might have to understand reality a little better first.

[ Science | 2007-02-19 18:56 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, February 14, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

NY Times. The Princeton ESP lab is closing after 28 years. Not because it didn't get any results or because it was discredited. Their experiments have continously shown that people can get better than random results with telepathy and telekinesis. Nothing earth-shattering, just consistently slightly better results than randomness. But they've also consistently been ridiculed by fundamentalist materialist scientists who'd rather sweep that kind of stuff under the carpet.“For 28 years, we’ve done what we wanted to do, and there’s no reason to stay and generate more of the same data,” said the laboratory’s founder, Robert G. Jahn, 76, former dean of Princeton’s engineering school and an emeritus professor. “If people don’t believe us after all the results we’ve produced, then they never will.” Yeah, that's a little sad, of course. But maybe someday science can be released from the clutches of Science-as-a-Religion, and the scientific method can be applied to other domains than what the prevalent group-think dictates.

[ Science | 2007-02-14 23:59 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, January 18, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

Yeah, I should have posted it last week, but some things got in the way. Science Daily: Research Into Procrastination Shows Surprising Findings. A scientist has spent 10 years studying procrastination, and he says he has a formula for it.Steel says motivational failures such as difficulty in sticking to diets and exercise regimes -- frequently the focus of New Year's resolutions -- are related to procrastination because impulsiveness is often at the root of the failure. "Temptations that are close at hand are difficult to resist. Addicts often relapse after returning from treatment facilities because drugs and alcohol become easily available and daily habits reassert themselves. Or we load up on bread in the restaurant before the meal is served. Or we check our email 10 times an hour instead of completing a project."

The good news is that willpower has an unusual capacity. "The old saying is true: 'Whether you believe you can or believe you can't, you're probably right'," Steel says. "And as you get better at self control, your expectancy about whether you can resist goes up and thus improves your ability to resist."

Steel has also come up with the E=mc2 of procrastination, a formula he's dubbed Temporal Motivational Theory, which takes into account factors such as the expectancy a person has of succeeding with a given task (E), the value of completing the task (V), the desirability of the task (Utility), its immediacy or availability (Γ) and the person's sensitivity to delay (D).

It looks like this and uses the Greek letter Γ (capital gamma): Utility = E x V / ΓD Eh, ok. That pretty much says ... nothing. But we can feel a whole lot more scientific if we have a formula.

I'd say the key issues in procrastination is that one has something one thinks one "should" do, but one hasn't visualized what really is involved, and it isn't wired up to stuff one really can perceive. It is just an idea, and one's immediate feelings and instincts are always what wins. To not procrastinate, one would need to do more homework. Visualize completely what is there to do, and what is involved. Decide whether it really is something one wants to do. And then backtrack from there, until one has practical and doable steps to get there, the first of which is right in front of you.

It is the same as the problem of To-Do lists that are filled with abstract stuff one has attention on, but where one hasn't done the work of finding out what it actually IS, what actually has to be done, and what the immediate next step is.

[ Science | 2007-01-18 17:14 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Thursday, January 4, 2007 |  |

|

|

|

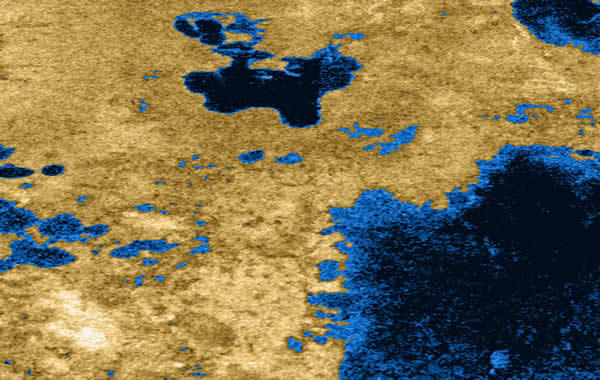

Pictures of methane lakes on Saturn's moon Titan here from NASA. Hm, I think I even see some Titanium cows walking around.

[ Science | 2007-01-04 15:37 | 0 comments | PermaLink ]

|

|

Page: 1 2 3 4 Older stories >> |