|

This is my dynamic, frequently updated homepage. This is a NewsLog, also known as a WebLog or Blog.

Everything is evolving, so don't assume too much.

People to watch:

Adina Levin

Andrius Kulikauskas

Britt Blaser

Catherine Austin Fitts

Chris Corrigan

Clay Shirky

Dan Gillmor

Dave Pollard

David Allen

David Weinberger

Dewayne Mikkelson

Dina Mehta

Doc Searls

Elisabet Sahtouris

Elizabeth Lawley

Euan Semple

Florian Brody

Frank Patrick

Gen Kenai

George Dafermos

George Por

Graham Hancock

Greg Elin

Hazel Henderson

Heiner Benking

Inspector Lohman

Jean Houston

Jerry Michalski

Jim McGee

Jim Moore

John Abbe

John Perry Barlow

John Robb

Joi Ito

Jon Husband

Jon Lebkowsky

Jon Udell

Jonathan Peterson

Judith Meskill

Julian Elvé

Julie Solheim

Kevin Marks

Lawrence Lessig

Leif Smith

Letecia Layson

Lilia Efimova

Lisa Rein

Marc Canter

Mark Oeltjenbruns

Mark Pilgrim

Mark Woods

Martin Dugage

Martin Roell

Mary Forest

Matt Mower

Max Sandor

Michael Fagan

Mike Owens

Mikel Maron

Mitch Kapor

Mitch Ratcliffe

Nathalie dArbeloff

Netron

Noam Chomsky

Paul Hughes

Peter Kaminski

Phil Wolff

Philippe Beaudoin

Ray Ozzie

Raymond Powers

Rebecca Blood

Roger Eaton

Roland Tanglao

Ross Mayfield

Scott Lemon

Sebastian Fiedler

Sebastien Paquet

Skip Lancaster

Spike Hall

Steven Johnson

Stuart Henshall

Thomas Burg

Thomas Madsen-Mygdal

Thomas Nicholls

Timothy Wilken

Todd Suomela

Tom Atlee

Tom Munnecke

Tom Tomorrow

Ton Zijlstra

Lionel Bruel

Loic Le Meur

Nancy White

Mark Frazier

Merlin Silk

Robert Paterson

Colby Stuart

Nova Spivack

Dan Brickley

Ariane Kiss

Vanessa Miemis

Bernd Nurnberger

Sites to watch:

Edge

Junto

Absara

Rhizome

Nanodot

HeadMap

Openworld

FutureHi

Imaginify

Do No Harm

BoingBoing

Smart Mobs

Webcamorama

MetaFilter

NotThisBody

Disinfopedia

YES Magazine

Collective Web

WorldChanging

Disinformation

Escape Velocity

Space Collective

Friendly Favors

Emergent by Design

Independent Media

Global Ideas Bank

Forbidden Science

Greater Democracy

ThoughtsOnThinking

Disclosure Project

Explorers Foundation

Manufacturing Dissent

Collective Intelligence

Action without borders

Free Expression Network

Co-intelligence Institute

Electronic Frontier Foundation

French:

Emmanuelle

Manur

Elanceur

Loeil de Mouche

IokanaaN

Blog d'Or

Le Petit Calepin

GeeBlog

Absara

Guillaume Beuvelot

Ming Chau

Serge Levan

Jean Michel Billaut

C'est pas Mécanique

I live in Toulouse, France where the time now is:

01:06

Unique Readers:

Primarily

Public Domain

Everything I've written here is dedicated to the

Public Domain.

The quotes from other people's writings, and the pictures used might or might not be copyrighted, but are considered fair use. Thus, overall, this weblog could best be described as being:

Primarily Public Domain. |

Syndication:

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](http://www.newciv.org/pic/valid-rss.png)

|

| Tuesday, July 27, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Via Global Ideas Blog, the Utopian World Championships. Yeah, that's a bit odd to have a competition for the best Utopia, but why not. I didn't read anything earth shattering so far, but it is a good exercise to design utopias. I'd probably have submitted something if I had noticed before.

[ Thoughts | 2004-07-27 11:06 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Bernie DeKoven on e-playing and e-learning, via Doc Searls: Bernie DeKoven on e-playing and e-learning, via Doc Searls:I call it "learning by dying" and I think it's probably one of the most powerful contributions that eplaying has for elearning. The most fun and efficient way to master most computer games is to play until you get killed, and remember what killed you. You usually have a few lives to sacrifice to learning. And you can always start over. This approach to learning has given most young people so much confidence in their competencies that, when confronted by a new game or new technology, they hardly ever need to look at the instructions. That is indeed a different way of learning. Different from what I grew up with. My kids quite obviously prefer to learn a different way than I. Is it better? For some purposes it obviously is. And more fun. And maybe the educational system needs to better catch on to this whole thing.

Learning by Dying. Something kind of disturbing about that, though. Although, it is maybe closer to how nature works than any other educational system we've cooked up. Maybe we need to recycle ourselves more often. Speed up evolution.

Anyway, he also quotes from an article Online Learning and Fun, about:"...the concept of meaningful failure. A player learns through trial and error and especially from mistakes, trying a different approach to accomplish the task at hand. Games often provide multiple opportunities and methods for a player to succeed. If a player fails using one approach, there are other ways to solve the problem. e-learning can leverage this gaming approach, offering multiple means of solving problems to encourage exploration and learning from failure." Yeah, we need to fail more often. Fail in the good and meaningful way. Gotta know how to die, and be reborn, stronger and smarter. The faster the better. We're too stuck in things we really ought to drop and move on from. Go to the next level.

[ Patterns | 2004-07-27 20:05 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Monday, July 26, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Via Smart Mobs: Phantom authority, self–selective recruitment and retention of members in virtual communities: The case of Wikipedia Andrea Ciffolilli discusses how apparently anarchic and uncontrolled virtual communities sometimes can exhibit amazing levels of cooperation and productivity. Specifically he focuses on Wikipedia, a stunningly comprehensive online encyclopedia that basically anybody can add to. Via Smart Mobs: Phantom authority, self–selective recruitment and retention of members in virtual communities: The case of Wikipedia Andrea Ciffolilli discusses how apparently anarchic and uncontrolled virtual communities sometimes can exhibit amazing levels of cooperation and productivity. Specifically he focuses on Wikipedia, a stunningly comprehensive online encyclopedia that basically anybody can add to. Virtual communities constitute a building block of the information society. These organizations appear capable to guarantee unique outcomes in voluntary association since they cancel physical distance and ease the process of searching for like–minded individuals.

In particular, open source communities, devoted to the collective production of public goods, show efficiency properties far superior to the traditional institutional solutions to the public goods issue (e.g. property rights enforcement and secrecy).

This paper employs team and club good theory as well as transaction cost economics to analyse the Wikipedia online community, which is devoted to the creation of a free encyclopaedia. An interpretative framework explains the outstanding success of Wikipedia thanks to a novel solution to the problem of graffiti attacks — the submission of undesirable pieces of information. Indeed, Wiki technology reduces the transaction cost of erasing graffiti and therefore prevents attackers from posting unwanted contributions.

The issue of the sporadic intervention of the highest authority in the system is examined, and the relatively more frequent local interaction between users is emphasized.

The constellation of different motivations that participants may have is discussed, and the barriers–free recruitment process analysed. Now, I have a more than cursory interest in what makes this work. Like many other people on the net, I have an almost religious belief that this can and will work. That self-organization works. But I've also initiated several different online environments where it didn't work as expected. Where pretty much anybody was free to join, and there was a noble common purpose to work on, but where it rather has tended towards degenerating into flame fights, and a curious absence of much of lasting value being produced. So I recognize that I don't really understand the keys yet. So, what might they be? Open source software constitutes the most popular and successful example of purpose–built community, characterized by cumulative dependency. Concerning the size of open source projects as a criterion for their classification, Krishnamurthy (2002) found that the community model is a poor fit for software production. Indeed, the top 100 mature projects on Sourceforge [3], are developed by one or a few individuals. However, Krishnamurthy does not argue that such result implies a sort of crisis in the open source community; as the author correctly recognises, large communities may exist and do things other than produce software. For example, communities may try out products and suggest new features. So, as far as software go, it might still be helpful with an enthusiastic community, even if it really is just a couple of people who do the main work. But, yes, there are other things to do than sofware, where many people might contibute more evenly. Wikipedia.com was born in January 2001 as a complementary project of Nupedia.com, which was aiming to create a freely available online encyclopaedia [4]. The publication of articles on Nupedia, in order to maintain high–quality, was based on a traditional review procedure of the publishers responsible for coordinating the project. The result of such process was that the volunteer contributors had to face a long and deterrent itinerary of submission, review and, if necessary, negotiation that ended up in very few articles published. At this point, the idea of Wikipedia emerged as a laboratory in which the advantages of massive collaboration could have been exploited, with the intention of choosing the best articles and letting them take the hard and costly review path leading to Nupedia.

The project has been successful. Six months after the birth of Wikipedia, 6.000 articles were written. Currently, there are more than 170,000 articles. [...]

Wikipedia is based on the Wiki technology that characterizes many Web sites. A Wiki community is open in the sense that it allows anyone to participate, freely viewing information contained in a site, permitting editing of that information as well. Editing Web pages can be done without submitting changes to a publisher and negotiating for them.

Why does this approach work? One might assume that graffiti attacks would eventually frustrate an approach on this sort of large scale. However, Wikipedia has been successful with a great deal of notable content as well as content in a state of constant improvement. For the most part, content disasters — in terms of quality — have not occurred. [...]

Wiki technology in a way literally cancels transaction costs for editing and changing information. Hence, this reduction in transaction costs acts as a catalyst for the development of the community. In turn, these reduced transaction costs means that there is full exploitation of massive collaboration economies. Hence, in the case of horizontal information assemblages, we might argue that any incentive that allows more authors to freely join in a given task, the larger the assemblage of information that is eventually produced (or in the case of Wikipedia, a larger number of articles is possible).

Another secret of the success of Wikipedia is related to the incentives that contribute to a "creative construction" of information, rather than a "creative destruction" of it. As noted earlier, I expected Wikipedia to be engaged in an endless war among reliable contributions and graffiti attacks that would have blocked the development of the Web site. In reality, that has not happened, basically because all changes made to any article are stored; it is possible to undo any unapproved modification with a single click. This makes the activity of littering a page extremely more expensive for an individual (in terms of time and reputation), than it is for anyone else. Therefore, also in this circumstance, it is a matter of costs.

Through this mechanism of editing and undoing meaningless changes or graffiti, an evolutionary process is fostered and only the best contributions survive the selection (Neus, 2001). Moreover, other factors contribute to Wikipedia’s success such as sources of authority and coordination. [...]

Whilst registered users can write articles, edit and discuss changes, administrators can exercise a certain degree of institutional authority. Indeed, they are allowed to ban IP addresses and permanently delete pages and their history. Such actions are undertaken when specific users are responsible for graffiti attacks, or when their writings and edits are not completely objective. Hence it is a general rule of the community that articles should be written from a neutral point of view. For example, one user was banned, who had written numerous contributions on German history [11]. These articles were perceived as right–wing by most, hence ignoring this standard of neutrality. In this case, the decision for banning the user was secured only after a long and lively discussion on the mailing list. [...]

Final policy decisions are up to one of the founders, Jimmy Wales. However, if this sort of benevolent dictator attempted to deviate from a neutral and objective policy towards content (for example, in order to push a specific political agenda), then the license provides a strong counter–balance to his power. The contributors may and should, in such a case, take the database and the software and set up a competing project. [...]

The case of Wikipedia, a successful project committed to the creation of a free online encyclopaedia, was examined. The principal reasons for the success of Wikipedia — namely, the drop in the transaction costs of submitting contributions and erasing graffiti — were described. It was shown how procedural and institutional authorities work for this site. In particular, the importance of reputation, as a source of authority, was emphasized. Reputation is accumulated through participation and that shapes a system of distributed authority in which every participant potentially may have a role in the development of the project. Hm, not sure if the keys really are clear. There's something more subtle in how a project is presented, and how it feels to people. If somehow the ingredients are mixed right, it is more likely to work. It might be very small nuances in how the purpose is described, or how the site works, that might make a big difference. But, yes, obviously, if the purpose is clear, and vandalism isn't worth the trouble, because it can be removed just as easily as it is put there, and it is just as easy, and more rewarding, to add something useful - that can all add up to a powerful package. But the focus is on how wikis work there. Do all wikis work? And how do these lessons apply to community oriented projects that aren't wiki based?

Obviously that one princple seems to be central: that it is more rewarding to do something constructive than something destructive. And that destructive activities are as easy, or easier, to get rid of as they are to add.

So, I can right away notice that in some kinds of environments, including some that I'm responsible for, it is often really more easy, interesting and rewarding to stir up some trouble and conflict than to do anything else. Not everybody wants to do that of course, but sometimes conflict gets many readers, many comments and a lot of attention. Not necessarily pleasant, comfortable attention, but attention nevertheless. And it seems to be an attention economy. Many online communities can be brought to a grinding halt by one person with a well-placed attack. So, unless the exploration and possible resolution of conflict is considered useful, which might be a possibility in certain types of communities, then it might be wise to rethink things a bit.

[ Organization | 2004-07-26 09:11 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Saturday, July 24, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Adina Levin talks about tools for mass listening. Adina Levin talks about tools for mass listening.The second half of the 20th century was the era of "mass broadcasting" -- a few anchors spoke, and the rest of us listing. The first half of the 21st century is about "mass listening" -- more of us participating in public conversation, using new tools to discover those conversations, catalyze opinion-forming and political action. Many of the tools that bloggers like are for mass listening, rather than for broadcasting. A feed aggregator, of course. And Technorati, Daypop and Blogdex and many other sites that make it easy to pay attention to what many people are saying. "Mass listening tools can provide a richer perspective than polling, which captures answers to loaded, pre-defined questions." That's addressed to politicians and big companies. How about getting better tools for noticing what people actually are talking about, and be responsive to that.

[ Information | 2004-07-24 16:11 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Tom Munnecke, in commenting on Mass Listening, says: Tom Munnecke, in commenting on Mass Listening, says: Listening is also part of the "Yes-And" Improv dialog form I am now researching. Improv actors have to listen to their partners... what a concept. They also learn that accepting a partners' offer is different than agreeing with it. And that "yes,but" creates a zero sum conversation, while 'yes, and' opens up a much more richer dialog. Ah, yes, thanks for reminding me. I've done Improv too. You know, improv is when one creates a reality together on the spot, which hopefully becomes interesting and maybe funny. One of the ground rules is to accept whatever anybody else brings into it, and build on it, rather than reject it if it doesn't suit you. If I come into a scene, and I had in mind that I was going to be Doctor Shtrumpfswanz, head of the psychiatric department, and somebody else beats me to it and greets me with: "Oh, the plumber, I'm glad you finally came!" - then I'm the plumber from then on. No use protesting and rejecting it, it would just ruin the scene. If somebody establishes that there's a table in the middle of the room, then there's a table in the middle of the room, no matter what clever alternative ideas I might have had. The answer is "YES, AND..". I must build on whatever everybody else have brought into the scene. For that matter, good improv comedy arises exactly when the participants are willing to accept what is there, and some rather surprising elements might have been brought together. And you find yourself playing tennis in a submarine, or something else you might not easily have found logical.

I frequently go back to find wisdom in the things I learned in improv. There's really a lot there that applies to life in general.

Improv works great when one is totally in the moment. One accepts everything that is there, and addresses it as real, and at the same time one channels something that might take it in just about any direction, and one has to track continuously with several other people who do the same. The moment you get stuck in your own head, getting bright ideas about what is supposed to happen, and not noticing what is really happening, it stops working. It is sort of an odd thing, like starting sentences without having any clue how they'll end. And finding that things often are better that way. Certainly more funny.

Anyway, I think Tom's point was how that kind of thing applies to regular conversation, and relating to others. The Yes-And principle. Hmm, I actually hadn't considered completely doing that in regular life.

What if I just accepted everything anybody brought into the scene? Hm, that's actually a hard one.

I was once waiting for a while in the reception of an insane asylum, as that also happened to be where one kept people who were on drug rehab. And some of the, eh, residents came up and chatted with me. Which was delightful. You know people who see spiders on the wall, or tell about their life as tabloid journalists or secret agents. None of which really was happening, but I didn't mind at all jumping into their reality and accepting what they were experiencing. Now, the psychatrist on the other hand was somebody it was no fun to speak with, but that's another matter.

But in the real world? What if I accept somebody else's reality, and just build on it, and see where it goes, rather than introducing any kind of "Yes, but ...[you're wrong]" kind of thing. I suppose that would really make for good listening. You allow them to reveal more of their reality, and see where it goes.

For that matter, that has also been a key ingredient in my work as a counselor. I'm not going to argue with the client. Whichever way they experience the world is what we'll start with. OK, my job is to help them transform it into something that is more useful to them. But I don't do it by negating what they believe. I do it by a kind of conversational judo. I use the force of their own worldview, and the way they structure themselves, to lead them towards transforming themselves. Works very well, if you manage to stay neutral, and you know something about how these things work.

But I must admit that I don't necessarily do that in a normal conversation. Oh, I'm open to many views, and I can leave many of them alone, but there will always tend to be some kind of tendency towards bringing you over to my view.

Can I give that up in all circumstances? Maybe. I do notice that it almost never works to negate what other people really believe in. It rarely works to try to WIN an argument by methodically destroying the 'opponents' statements. And yet that's what most of us do half the time.

It is the 'shoulds' that get in the way most of the time. How somebody else 'should' think, and how things 'should' be. But the fact of the matter is usually that they actually aren't like that. The 'shoulds' are a mental hallucination we superimpose on reality. Really, the best way of changing anything is to accept what is already there, and then look for available paths of maybe helping it change into something else. And if there are no available paths, you might just allow things to remain the way they are.

Interestingly the more in balance we ourselves are, the less we feel a need for correcting everybody else's worldviews. The more enlightened you yourself are, the less you are obsessed with making everybody else be like you. Ironically, as we could say you had all the more reason to do so, if you've found some kind of nirvana that most others haven't.

But maybe the bigger truth is that the world really would work better if we could accept different world views, and simply allow them to evolve naturally. And maybe life would be more interesting and entertaining if we dropped the mistaken idea that we all live in exactly the same world, and we're supposed to live by the same rules.

[ Patterns | 2004-07-24 17:07 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, July 23, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

What is Psychogeography: What is Psychogeography: Psychogegraphy is the study of the effects of geographical settings, consciously managed or not, acting directly on the mood and behaviour of the individual".

Psychogeography research is carried through non-scientific methods such as the derive, aimless drifting through the city, trying to record the emotions given by a particular place; and mental mapping, the production of mood-based maps.

Psychogeography was developed as a critique of urbanism by the Lettrist International and then by Situationist International in the late fifties. Today, it is pursued by artists, radical thinkers and, on an academic level, geography researchers. Hm, sounds intriguing. But I'm not sure I get it. What exactly do you do? Wikipedia has some more details and types of psychogeography: Disagreements have led to many variations in the practice which have included the following forms: Debordian; Literary; Generative or Algorithmic; and Quantum. Various factions claim to be or accuse each other of being: academic; occultist; avant-garde; proletarian; or revolutionary. Just makes me more confused. I seem to get a better idea from this text: Psychogeography and the dérive. ...The situationists' desire to become psychogeographers, with an understanding of the 'precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals', was intended to cultivate an awareness of the ways in which everyday life is presently conditioned and controlled, the ways in which this manipulation can be exposed and subverted, and the possibilities for chosen forms of constructed situations in the post-spectacular world. Only an awareness of the influences of the existing environment can encourage the critique of the present conditions of daily life, and yet it is precisely this concern with the environment which we live which is ignored.

"The sudden change of ambiance in a street within the space of a few meters; the evident division of a city into zones of distinct psychic atmospheres; the path of least resistance which is automatically followed in aimless strolls (and which has no relation to the physical contour of the ground); the appealing or repelling character of certain places - all this seems to be neglected." So, like an awareness of the stuff of pattern languages in the environment. Charting how environments influence us, based on some kind of non-linear exploration. Mapping outer invironments based on inner states. And changing the rules about how we relate to the environment. An infinite game. What is a dérive? Concealed by the functional drudgery of city life, such areas of psychogeographical research were seen as the ground of a new realm of experiment with the possibilities of everyday experience.

One of psychogeography's principle means was the dérive. Long a favorite practice of the dadaists, who organized a variety of expeditions, and the surrealists, for whom the geographical form of automatism was an instructive pleasure, the dérive, or drift, was defined by the situationists as the 'technique of locomotion without a goal', in which 'one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there'. The dérive acted as something of a model for the 'playful creation' of all human relationships. [...]

To dérive was to notice the way in which certain areas, streets, or buildings resonate with states of mind, inclinations, and desires, and to seek out reasons for movement other than those for which an environment was designed. [...]

...the situationists developed an armoury of confusing weapons intended constantly to provoke critical notice of the totality of lived experience and reverse the stultifying passivity of the spectacle. 'Life can never be too disorientating,' wrote Debord and Wolman, in support of which they described a friend's experience wandering 'through the Harz region of Germany while blindly following the directions of a map of London.' Hm, what a weird and splendid idea. Anyway, this all seems to fit into my ongoing quest for the deeper patterns of life, beyond the superficial and confusing details that are swirling around us. An example of a situation-creating technique is the dérive. The dérive is the first step toward an urban praxis. It is a stroll through the city by several people who are out to understand the "psychogeographical articulation of the modern city". The strollers attempt an interpretive reading of the city, an architectural understanding. They look at the city as a special instance of repressed desires. At the same time, they engage in "playful reconstructive behavior". Together they turn the city around. They see in the city unifying and empowering possibilities in place of the present fragmentation and pacification. This "turning around" or détournment is a key strategic concept of the Situationists. Détournment is a dialectical tool. It is an "insurrectional style" by which a past form is used to show its own inherent untruth-- an untruth masked by ideology. It can be applied to billboards, to written texts, to films, to cartoons, etc., as well as to city spaces. Marx used it when he "turned Hegel on his head." He used the dialectic in the study of history to expose the ideological nature of Hegel's idealism. The Situationists use détoumement to demonstrate the scandalous poverty of everyday life despite the plenty of commodities. They attempted to demonstrate the contrast between what life presently is and what it could be. They wanted to rupture the spell of the ideology of our commodified consumer society so that our repressed desires of a more authentic nature could come forward. The situation is based on liberated desires rather than alienated ones. What these desires are cannot be stated a priori. They will emerge in the revolutionary process of situation-creation, of détournment. Presumably, communality, unification, and public urban space will emerge as more desirable than commodification, fragmentation, and privatization. OK, not the easiest stuff to read, but I like it. Wonder who's doing things like that around here. Sounds like something French avantgarde art and philosophy types would easily get into.

[ Culture | 2004-07-23 15:35 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Dan Bricklin writes about software that might last for a really long time. In many human endeavors, we create infrastructure to support our lives which we then rely upon for a long period of time. We have always built shelter. Throughout most of recorded history, building or buying a home was a major starting step to growing up. This building would be maintained and used after that, often for the remainder of the builder's life span and in many instances beyond. Components would be replaced as they wore out, and the design often took the wear and tear of normal living into account. As needs changed, the house might be modified. In general, though, you thought of a house as having changes measured in decades.

Likewise, human societies also create infrastructure that are built once, then used and trusted for a long period of time. Such infrastructure includes roads, bridges, water and power distribution systems, sewers, seaports and airports, and public recreational areas. These also would be used and maintained without major modifications after they were built, often for many decades or even centuries.

By contrast, software has historically been built assuming that it will be replaced in the near future (remember the Y2K problem). Most developers observe the constant upgrading and replacement of software written before them and follow in those footsteps with their creations. So, how about if we started building software as infrastructure that was meant to function for a great many years, despite changing conditions? Not that he provides the answers for exactly how to do that, but it is a call to think bigger.

It is not just about the software itself, of course. It is also about the format and media of data for example. A piece of paper can last hundreds of years. A digital CD surprisingly starts rotting within 10 years or so. It seems like we have access to 'everything' on the net and in various databases. But really we only have access to the most recent stuff, that happens to have been made in a recent format that still is popular. Only fairly rarely do we go back and convert the old stuff into the new formats.

Anyway, he specifically calls for the development of an different 'ecosystem' for societal infrastructure software. Certainly makes sense, as our societal infrastructure increasingly is totally dependent on databases and software. Makes the whole foundation of our society kind of shakey if it is based on pieces that stop working after only a few years.

[ Information | 2004-07-23 16:12 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, July 21, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

So, over the years I've written all these software modules for an assortment of online purposes. Like: So, over the years I've written all these software modules for an assortment of online purposes. Like: - Weblogs

- Bulletin Boards

- Chat Rooms

- Calendars

- File Sharing

- Membership Sites

- Online Directories

- Work Groups

- Personal Information Management

- Shopping Carts

- Online Website Generation

- Forms and Database Generation

- Mailing List Management

- DNS Administration

- Server Monitoring

- Content Management

- News Feed Aggregation

- Image Manipulation

- ... and Wikis

And probably some I'm forgetting right now. All of it is in use in one place or another. And some of it isn't half bad. For that matter, some of it was a bit ahead of its time. And the users of some of these things seem exeedingly happy with what they do.

But there's a considerable problem with spreading oneself that thin as a programmer. Most succesful programmers will do one or two great things, or they'll have a team to work with.

Anyway, since I don't really, the result is that all of my modules are somewhat unfinished. Or, rather, they work well in the particular setting they were made for. As long as I manage the server, and fix things that go wrong, and tweak them for new purposes. But it doesn't mean they're easy to export.

I've been paid well for making some of these things, and some of them I made because I needed them myself, or to make nice places to hang out online. But generally I've never figured out how to make the jump to making a business out of any of them. And neither have I made the jump to package them as open source packages that people can just take and use, and others can contribute to.

And, well, Internet time moves quickly. So, while I can still enjoy that my weblog program does some things better than any other weblog program I've tried, other pieces are at the risk of slipping into obscurity, by being somewhat outdated and mediocre in how they look and what they can do. And across the board I've missed a lot of opportunities for doing something with these things at a higher level.

I can't count the number of times I've shown a selection of these programs to some business-wise person, who's told me that I could take any one of these and turn it into a thriving business. Usually accompanied by stories of people who've made it big with some fairly mediocre piece of software or other product, that they just managed to position well, and work hard on it, until it became a viable enterprise.

But which one should I pick? I'd be leaning towards most all of them. That is, a membership site where the users can easily set up an assortment of different resources, by picking from a menu and doing a bit of configuation. OK, so you want a website, and it should have a weblog and newsfeeds and a shopping cart and an event calendar, and you want an intranet for your employees with spaces for different teams and wikis, etc. Shouldn't be any great reason you shouldn't be able to have that up and running in a day or so, without needing to download any software or having to know any HTML.

I call that OrgSpace. That's a registered trademark. There's a corporation ready in England with that name. I've talked a good deal with Julie about launching something of that nature, starting back when we had a company in L.A. called Synchronicity. I've discussed pieces of it to great length with quite a few people.

But it doesn't work if I'm the sole programmer. And I'm sofar not as much of an entrepreneur as I'd like to be. So, it is stranding a bit both on the level of finishing the software, and on the level of doing the normal stuff one does to start and run and grow a business.

It could take all sorts of formats and directions. Like, a particular software piece might be a separate product in itself. Doesn't have to be an all or nothing proposition. It depends on what other people are inspired to be part of.

But I need programmers to collaborate with. We're talking about PHP. People who aren't as inclined to start from scratch as I am, but who'd feel inspired to do great things with pieces that already are 70% there, and to work as part of a team. This is in no way beginner's stuff, so some hardcore coding ability is needed.

A graphical design and layout person would be very helpful too. Most of my sites look like they were made in 1995, mostly because they actually were.

Some business help would be a good thing. I'm not ignorant of the basics, so it is maybe more a matter of coaching. Well, of course if one of you just wanted to finance the whole thing, that would certainly make everything easier.

But, barring that, we're talking about people who're interested in freely collaborating for the purpose of future business, or for making useful open source software, and useful online services. Or in making online communities and networks that work better. Whatever inspires you, and whatever format that is structured in. I can easily think of a variety of avenues for business or rewarding non-profit activities. I just need to get beyond wearing the programmer hat all the time. And I'm not going to give away just all the secrets here.

My own problem is that I'm a perfectionist, so I'm not the right person to do everything myself. It doesn't mean I'm necessarily hard to work with, but it means that I'm usually not sufficiently happy with what I do to get it out the door. You know there's the wise rule of 80/20 that says that you go for making 80% of what needs doing, and you get it out the door. And in the next iteration you do 80% of what is left. The hard lesson for a perfectionist to learn is that other people than yourself usually are quite happy with the 80% solution, as long as you actually put it into their hands.

A few little anecdotes:

I gave my shopping cart code to somebody once, when I considered it just half-way done, even though it basically worked. Somebody who was a much more novice programmer than myself. He worked hard for a month and set up a flashy online shopping mall site, where quickly hundreds of customers had paid for having their own online stores.

I wasn't very satisfied with my online website design tool, even though it actually did much more than anything else available at the time. Unbeknownst to me at first, a big Beverly Hills newspaper used the beta test demo version to put their whole paper online every week, with all previous issues archived. I would have said it was impossible, as it wasn't really a content management system suited for that purpose, but they found ways of working it so that it did what they needed, and were quite happy with it.

I made this opt-in mailing list management system. It handled mailing lists with several million subscribers and daily mailings. One of the companies using it wanted a faster mailing engine. I knew very well what to do, but I needed a C programmer to do a fairly minor piece for me, but instead I insisted on trying to do it myself, and procrastinated it. So instead they spent 1/2 million dollars or so on somebody else's system, which was inferior on various other counts, but it mailed really quickly, and it was supported around the clock by a team of people, where I was just myself.

You catch the drift, I'm sure.

So, if you're the right kind of person, and any of this is of the slightest interest, let me know.

[ Programming | 2004-07-21 06:45 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

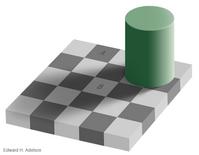

Is square A and B the same color or different colors? Want to bet? They ARE the same color, but almost all of us can't see it, before it has been proven to us, and we've stared at it another five minutes. Your brain is so good at filtering out the effects of shadows so that we can make the best possible guess at what we're seeing. So good that we actually can't see what is really there, but only what is supposed to be there. The illusion is most obvious in the large version. See here for the details, and proof of why it is so. If you still don't believe it, you'll have to download the image and cut out little pieces of it in a graphics program, and put them next to each other. Is square A and B the same color or different colors? Want to bet? They ARE the same color, but almost all of us can't see it, before it has been proven to us, and we've stared at it another five minutes. Your brain is so good at filtering out the effects of shadows so that we can make the best possible guess at what we're seeing. So good that we actually can't see what is really there, but only what is supposed to be there. The illusion is most obvious in the large version. See here for the details, and proof of why it is so. If you still don't believe it, you'll have to download the image and cut out little pieces of it in a graphics program, and put them next to each other.

[ Information | 2004-07-21 13:56 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

If my weblog is a little too dull for you, try to pornolize it. That'll give you the dirty pornstar version. It seems to do a particularly good job at insulting (or flattering) everybody in my blogroll. You can do the same with any site. OK, it is tacky, and not particularly smart, but it is a good laugh.

[ Culture | 2004-07-21 14:04 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Tuesday, July 20, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Anthony Judge mentioned his article The Isdom of the Wisdom Society. Anthony is one of the smartest people I know of, and his enormous site and his articles are somewhat intimidating to approach. Certainly clear enough to read, but he covers so much ground that it takes your breath away a bit. Anthony Judge mentioned his article The Isdom of the Wisdom Society. Anthony is one of the smartest people I know of, and his enormous site and his articles are somewhat intimidating to approach. Certainly clear enough to read, but he covers so much ground that it takes your breath away a bit.

This piece was for the UN World Summit on the Information Society, and is exploring information and knowledge and wisdom, and then points to what's maybe at the core - what IS and how to BE with it. Many studies explore the importance of the distinctions in the sequence from "data", through "information", then on to "knowledge", and finally to "wisdom" [more]. At each stage there is a much-studied challenge of "management" (as in "information management" and "knowledge management"). Arguments are also made for the importance of a corresponding "information society" or of a "knowledge society" -- perhaps expressed as a "knowledge-based society". But clearly it is easiest to argue the case for an "information" focus, especially to hardware, software and information vendors -- hence the title of the UN World Summit on the Information Society. It is more challenging to make a case for a "knowledge society", especially since "knowledge management" is in process of being disparaged as a fad term lacking any real content -- notably in those corporate environments that claim to practice it. And yet it is precisely the transfer of knowledge, in the form of "know-how" that has been a preoccupation of the United Nations over many development decades. But knowledge is a troublesome thing to get a handle on. If I know one thing, and you know another, and a lot of knowledge is hidden in the library or on the net - what do we really know? Is it knowledge if we put it all in the same database? We so easily end up scattering both our information and our knowledge about, and apart from ourselves. Maybe splitting something apart that really isn't apart. Like ourselves.

What we usually really need is the wisdom. To somehow transcend keeping track of the information and the knowledge, and somehow have the instinct for making good decisions, even in difficult circumstances. The distinctions between data, information and knowledge are increasingly problematic as is to be seen in efforts to give content to "knowledge management". It is perhaps helpful to see the sequence as a progression from more objective to more subjective -- namely an increasing dependence on judgement, cognitive ability, experience and the capacity for synthesis (see Evaluating Synthesis Initiatives and their Sustaining Dialogues, 2000). Whilst software can be provided to manage information, those packages designed in support of "knowledge management" are far more dependent on the knowledgability of the user. Similarly, whilst data and information can be readily explained, this becomes more of a challenge in the case of knowledge. This is exemplified in the case of appropriately ordered information on a food recipe. Although the recipe may be followed, it is only in the light of the knowledge acquired through past learning and experience that there is any guarantee that the result will be tasty. OK, we need to understand wisdom better. Wisdom involves subjectivity, and it isn't easy to just break it down and explain it. It can't easily be transferred.

Wisdom seems more intimately bound to space-time than information and knowledge. But in a way that makes it sort of timeless. It has more to do with the quality of how you know and how you go about things than with the actual content. It involves a quality of discernment largely absent from conventional knowing. So, maybe that all leads us towards the mysterious quality of being present, of the "Now", of what IS, and how we act in it.Paradoxically, as one might expect with respect to a "timeless" quality, its uniqueness derives from a way of "being in the present". This focus on the present is echoed in many sources of wisdom -- as the key to appropriate action in the more extended framework of space and time. Its proximity is for example stressed in various religions. Judaism and Islam recognize that the separation between Heaven and Hell is but a "hair's breadth" -- echoed by Zen in the acknowledgement that the separation between enlightenment and ignorance is again just one "hair's breadth".

It is for this reason that -- playfully -- it is suggested here that the domain of wisdom might usefully be recognized as "Isdom". This might be seen as corresponding to terms such as "Kingdom", "Dukedom" or "Fiefdom" -- except that the focus is on the domain of "is-ness" in the present. Well, that's very refreshing. The Zen of the moment. Again, hard to take apart, by its very nature, but it can be hinted at, maybe a bit poetically.As the domain of the present moment -- the present instant -- Isdom is a place of being characterized by a quality of appreciating that moment, and sustaining that appreciation. It might be understood as the mode of expression and interaction in the instants before conventional exchanges occur. As such it resembles a kind of existential foreplay -- in part made of glances and understandings that are global in their quality -- an interplay of being. For example, one international event focused on The Butterfly Effect as the "coordinates of the moment before discovery". It is the sparkle on a pool -- or in a person's eyes (or those of any other animal).

The moment may be imbued with a sense of incipient knowing or of intuitive re-membering -- of re-cognition. It may be understood through the anticipatory quality of "happening" -- a sense of in potentia -- as when encountering a significant other (perhaps for the first time). It is, for example, the instant before any process of falling in love -- "at first sight" -- namely before intentionality or action of any conventional kind. Well, I'm not going to go on and quote the whole thing, but Anthony goes on to explore how we might possibly "contain" the is-ness. It so easily gets spoiled and reverted into banal normalcy. So hard to hold on to. It is like the plasma needed to create nuclear fusion. The hardest part is to keep it together without it being messed up by the stuff that isn't it. How can the present be reified - made more real? How can we recognize and tap into FLOW? We might have to look for answers in quite different places than what we normally use to take things apart and analyze them. Indeed the addictive "normality" of our habitual world is exactly what keeps us from understanding the zen of the present moment, from tapping directly into the consciousness of wisdom and becoming more fully alive. The things we need to *get* easily border on craziness when seen through the eyes of our collective normalcy. The things we can neatly describe and categorize are not it. From the Tao Te Ching: The Tao that can be described is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be spoken is not the eternal Name.

The nameless is the boundary of Heaven and Earth.

The named is the mother of creation. To really BE in the present moment, and to be in touch with our inherent wisdom, we need to get beyond most of what we can think of putting a name to. Yet, the world is made of the stuff that is observed and named. Ah, delightful paradoxes.

[ Knowledge | 2004-07-20 14:55 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

So, I wrote a wiki program. Now, that is maybe stupid, as there are plenty of excellent wiki programs around. But the ones I first looked at didn't have the combination of features I was looking for. OK, looking closer, there really are some impressive choices out there. But, again, not necessarily how I'd want to do it. So, I wrote a wiki program. Now, that is maybe stupid, as there are plenty of excellent wiki programs around. But the ones I first looked at didn't have the combination of features I was looking for. OK, looking closer, there really are some impressive choices out there. But, again, not necessarily how I'd want to do it.

And then I have the troublesome tendency to feel really compelled to make my own programs from scratch. Oh, not everything, but the moment I stare at somebody else's code that I need to make changes to, to make it do what I want, and it is likely to take more than an hour or two, it is inescapable. I instantly imagine that it is easier to just do my own, rather than spell myself through the odd ways somebody else has done it. Oh, in reality, it is never faster or easier. But I do usually end up with something I'm comfortable with, and that I can easily add new features to.

Anyway, it works now, even though it only does the rather basic stuff that most wikis do. Being able to edit a page, keeping track of revisions, searches, recently modified list, user login, various kinds of markup, etc. There's a little page about it here. It is a PHP program, using MySQL database, attempting to be standard and use XHTML and CSS.

I'm trying to force myself, for the first time, to go through the necessary steps to successfully give my software away. Oh, lots of people are using my software for free, that's not what I mean. I mean, the open source way, where you can actually go to a site and download the latest version, and install it without too much trouble, if you're a bit technically minded, and you have a linux server account. Now, that is not altogether trivial. There's quite a jump from being able to run something on my own server, to expecting that other people can go and do the same without running into a wall. I usually make it difficult to do that by adding a lot of features to my programs, and linking them all together, so that it is difficult to extract one of them and make it survive in the wild. So with this program I'll try to restrain myself a bit.

Now, if it is its own program, it needs a name, of course. Wiki programs have silly names that usually rhyme more or less badly with "wiki". So, how about Ziggy Wiki? Doesn't seem to be taken.

Some of the features I have in mind are things like:

- Being able to embed a number of different kinds of objects in a page, like RSS feeds, web service calls, calendars, etc.

- Using a wiki to design and generate a "real" website.

- Importing content from various non-wiki sources

- Organizational features, categories, etc.

- Image handling and storage

And I guess I'll integrate it as a parallel dimension to my weblog program somehow. Probably starting by making my own public wiki and seeing how it works out.

To test my wiki, try the SandBox where it shouldn't do any damage.

[ Programming | 2004-07-20 15:01 | 0 comments | PermaLink ]

|

|

| Sunday, July 18, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

I occasionally wake up sweating, thinking I've forgotten to do my paper route, and undelivered newspapers are stacking up somewhere. When awake, the feeling gets replaced with a vague feeling that there's something somewhere that I've forgotten, and it is important. Of course I haven't had a paper route for, oh, close to 30 years, so it probably isn't that. Except for that I'm not totally sure if I handed in my resignation, so maybe there really is 20 tons of bundles of old newspapers standing there, and a lot of angry customers waiting for their morning paper. How do I know? I occasionally wake up sweating, thinking I've forgotten to do my paper route, and undelivered newspapers are stacking up somewhere. When awake, the feeling gets replaced with a vague feeling that there's something somewhere that I've forgotten, and it is important. Of course I haven't had a paper route for, oh, close to 30 years, so it probably isn't that. Except for that I'm not totally sure if I handed in my resignation, so maybe there really is 20 tons of bundles of old newspapers standing there, and a lot of angry customers waiting for their morning paper. How do I know?

But the feeling is quite close to how I relate to many kinds of information. You know, there's something I should know about, and that I should be doing something about, but currently it is disconnected from what I actually do, and I don't quite remember. But it might come back and bite me at any moment, at which time the *information* will clearly show that I'm an idiot who's not doing what I'm supposed to. Until then, the information might well be hiding somewhere where I'm not looking. So, where should I look to find all the information I should be aware of?

Paying bills is a bit like that for me. Relations with public authorities certainly is. I have the sneaking suspicion there's probably some big things I should be doing that I'm not, like paying taxes or having the proper licences, permits and immigration papers. I have some vague ideas. But, I look around me, and there's nothing in my environment that tells me much about any of those things. It takes some hard work to go and track down the information I'm supposed to have, and then figuring out what to do with it. And I never know if I got the whole picture. Yet, there's no excuse for not knowing the law. Meaning, there are 10s of thousands of pieces of information I really should know about, many of which could put me in jail if I didn't act correctly in accordance with them. Oh, most other people don't know them either, but they somehow manage to get the most vital pieces, and then they look around themselves and see what other people do, and they figure they can't go all wrong if they do roughly the same.

My point is that information is typically something disconnected and abstract. Data certainly is. It is some kind of extract representation of something, which possibly might be real. Information is when we put some of that data together so it seems to say something coherent.

I get a bill in the mail. That's a datum, or maybe several. If I study it and discover that, aha, I'm supposed to pay this before the 10th of next month, and this is the amount, then that is information. At that point it is still unconnected to everything else. Who says I'll remember that next month, or that I have any money at that time? Where do I put this thing so I find it again? Well, if I really think it is terribly important, I make some kind of system to remind me. I make a folder for that creditor, I write it in the calendar, I try to estimate my budget over the next month. Of course, you say, everybody does that. But it is not that *of course*. It is just that you're used to living in an information world where things like bills and deadlines appear to be real. Even though they're disjoined and often inconsistent abstractions, several levels removed from anything real.

If you call up Microsoft for tech support, based on some odd problem you have with Windows, they'll usually end up telling you that the answer is there, plain and clear, in technical note number 17536, and you're a bit of an idiot because you didn't know that. They have their information asses covered, just like the law. It is your fault you don't know.

To be fair, most open source mailing lists work like that too. You ask a question, and there will always be somebody quite willing to tell you how stupid you are because there's some file somewhere that has the answer on line 514. And you didn't know. It is a bit of crime to not have processed and tabulated all the information in the world.

In a society like the french, often things aren't said explicitly, but it is assumed that you'll somehow know. The school doesn't necessarily give you a piece of paper that says when vacation is over, because it is assumed that everybody knows. If you apply for being admitted into a new school, they might not even bother to tell you if it was accepted or not, because you somehow ought to figure that out by yourself. The business world works like that too in many ways. You're sort of supposed to guess what is going on, even though the information isn't readily available, and your boss isn't talking. You've gotta be well networked, drawing on an extensive intelligence network when you do anything. You're supposed to know things, but there might not be anybody who tells you exactly how. And the available data itself might not help much.

There's an implicitly idea somewhere that data adds up to information. Which potentially might be structured into knowledge. And if you then really internalize it, it might become wisdom.

It is a questionable model. It assumes that the direction is from disjoined snippets of data towards something more integrated and useful. Who says it works like that? Nature doesn't seem to me to work like that. There nothing quite equivalent to data out there. Nature includes lots of systems that have partipating elements that send messages to each other. A plant or animal that is trying to procreate often sends out millions of little seeds or pollen or eggs. And there are millions of ways they might get activated. DNA is certainly information, but it is replicated billions of times. There are billions of ways that DNA might hook up and produce the next generation. Billions of signals with certain receptors might be met with billions of possible counter-parts that have matching receptors. It certainly doesn't depend on one little piece of information hidden once somewhere, which somebody has to remember to go look for.

That is where our informational systems tend to go wrong. We put something in some suitable place, and then one is just supposed to know where to find it. And, oh, one can make all sorts of reminders that makes it easier. Like, if on the web a piece of information is stored in some place, other sites can link to it, and people can make bookmarks, and they can write a little note for themselves to remember where it was. And you can go search in a search engine. And that helps, and somehow most things work out. But it still seems vastly inferior in some way to the relatively effortless manner information is used in the natural world. Our systems depend on somebody remembering what to look for, at the right time, and discovering the right context. It is very fragile.

Just like our technology, which is built on similar models. One little wire is disconnected or one little comma in the wrong place in a program, and the car doesn't start or the space probe misses Saturn. Our constructions often have many single points of failure. Nature generally doesn't.

We can learn, I'm sure, from nature, how to help things link up more often, and more reliably. Of course what I really want is for the information I need to be available exactly when I need it. I want the information to come to me at the right time, and I want to not have to analyze large amounts of data to find out what is going on. I want to be reminded of my bill at a reasonable time to pay it, and I want the expectation of having to pay it to be wired to my budget somehow. I would want to know of course, the moment I try to buy something else frivolous that it would mean that I couldn't pay that bill next week. Well, really I'd rather not have a bill. I'd rather that my economic metabolism took care of the needed energy exchanges, continuously.

A lot of our information use carries with it the phenomenon of "Now the cake should have been in the oven for 1/2 hour". You know, you get to a certain point in the recipe and it tells you that there's something you should have done at an earlier stage, but you weren't aware of it at that stage. I might put a reminder in my calendar to pay a bill, and when it rings, I will remember that I should have made sure I had money to pay it. Which I might not have done.

Disjoined information doesn't necessarily add up. There's no guarantee it adds up to meaningful information and useful knowledge. Just because you spread a lot of screws and other mechanical parts around on the floor there's no guarantee you can construct a refrigerator from it. If I started with a working refrigerator and dismantled it, then I likely could. But independently aggregated bits and pieces, no. And most of our information is like that. It doesn't come from a dismantled whole, but rather from unrelated bits and pieces, which you're then supposed to put together into a whole. Which is next to impossible.

We are pretty good at managing anyway. Despite that we live in a sea of disjoined information, we're pretty good at creating some kind of network between them and making useful things happen. We do it in a rather primitive low-tech kind of way, maybe. Most countries have an enormous and ridiculously complicated system of law. Most people, including the politicians who wrote the laws, and the lawyers and judges who interpret them, do not at all have an overview of what it adds up to, and many laws contradict each other. So, for normal people the answer is usually to look around you and guess at what the laws seem to be. Stop for red lights, don't steal other people's stuff, etc. And the lawyers will just search for laws that support a particular point when the need arises. We find a pragmatic way of dealing with it, in the face of the impossibility of knowing what the laws actually say in total. So what do we really know, if the pieces are scattered all over, and we're just barely coping?"In what sense is a thing known if five hundred people each know one constituent of it and nobody knows the whole? Or again; what if this truth has a thousand constituents and half of them are not known to anyone, but only stored in libraries? What if all of them only exist in libraries? Is it enough that somebody knows how to look them up if they should ever be needed? Indeed is it enough that this person should have access to a system which will look them up? Does the enquirer even have to understand the questions which these truths answer?" - Mary Midgley (Wisdom, Information and Wonder: what is knowledge for? 1989) Is that really the best we can do? Can't it all connect better? Well, one possibility is a structured semantic web. If all information is meticulously categorized and related with all other information. Possibly in some huge all-encompassing hierarchy. I don't know how likely or possible or even desirable that is. Another possibility is making everything easier to find, and to constantly look for matches for everything. That's more like nature's way, I think. You put everything that needs to be remembered out in loads of redundant copies. And then loads of little pieces are constantly looking for matches to what they're looking for. You know, a Synchronicity Engine of some kind.

There's still some major key missing, though. We need a paradigm shift that takes us from the overwhelming complexity of scattered information to a world where things might again be simple, but at a new level. You know, you're hungry, there's an apple on the tree in front of you, so you eat the apple, and you feel good. That kind of simplicity. You're tired and you sleep. But while at the same time being globally connected with a vastly bigger network of people and information. Rediscover the simplicity in a higher order of complexity. I have no doubt that it is there. And if we don't find it, it is probably because we still address information complexity the wrong way.

[ Knowledge | 2004-07-18 10:15 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Friday, July 16, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

Hm, didn't get around to blogging for a week, which is unusual. For me it is a certain rhythm, that is real easy when I do it every day. Requires very little energy and flows effortlessly. But if I get out of it, either by traveling and not having access to my normal channels of information, or if I just get busy with something else for a few days, it is suddenly an effort to figure out how to start again. Hm, didn't get around to blogging for a week, which is unusual. For me it is a certain rhythm, that is real easy when I do it every day. Requires very little energy and flows effortlessly. But if I get out of it, either by traveling and not having access to my normal channels of information, or if I just get busy with something else for a few days, it is suddenly an effort to figure out how to start again.

Doesn't matter a whole lot. There's no change in how many people drop by my blog, really, as many of them come from search engines, and there's plenty of stuff in the archive. It is really just a psychological thing for the blog author.

Many people who think or talk about blogs, like at BlogTalk, worry about the phenomenon of bloggers who stop blogging. People present statistics that show that lots of people have abandoned their blogs, or projections that show that before too long there will be more abandoned blogs around than active blogs. So what? There's sort of an implied assumption amongst people who are blog advocates that everybody really ought to be doing it. Which isn't going to happen, unless a blog gets to be redefined as something else. A Personal Presence Portal maybe. But even then, a majority of people really have little interest in being more visible and present on the Internet. Lots of people try to be as invisible as possible. Blogging really appeals most to people who think of themselves as having something to offer to the world. Who have a message, or particular viewpoints on things, or something to sell, like themselves. Yes, you might just be writing your thoughts or taking pictures of the cheese sandwich you had for lunch, but the underlying factor is that you like sharing it, and you're happy with the attention. Maybe you only want the attention from a very limited group, like your friends or your family, but you're never posting things only for yourself, even if it works well to pretend that you are. It is a bit of a paradox. The focus is usually on you, and most people write kind of like they're speaking to themselves, not directly to anybody particular, and you're somehow just cataloguing what you're interested in, or what you're doing, but the format wouldn't work at all unless there was somebody to share it with.

Allan Karl writes about when a blog is dead. He shares his own anxiety about not blogging and mentions another article by Mary Hodder that notes that some people are travel bloggers, who write predominantly when they're traveling somewhere interesting. Which Allan often seems to do. So while this quick paragraph reduced my blogging anxiety for a fleeting moment due to the fact that for the past few months the majority of my active posts have happened while I have frolicked somewhere around this grand planet, the fact is I feel that like a newspaper, magazine or newsletter the key word is "periodical". Now define this as you wish but for me a blog is a published piece. And as such it should be updated on a regular and recurring interval. Hence, the result of my anxiety when I have a lapse of week (let alone a day) or two where the pressure (on myself) to blog mounts until I finally grapple with some material I feel to be of value and interest to readers of the Digital Tavern. Personally I usually have much greater difficulty blogging when I'm traveling, unless I end up somewhere with an always-on WiFi connection, and I have sufficient free time.

Stephanie Booth talks about (mostly in French) bloggers who stop blogging, picking up on some themes from BlogTalk. You know, there's the Blog Blues, which most bloggers recognize. The times when you feel you really should be writing something on your blog, but it doesn't flow, and you have an assortment of anxieties about that. And there's the phenomenon when you start that you feel you have no readers, so it is not worth it. You know, somebody's first post is "Test, test, test", and the second one is "Anybody there?". Nobody comments, and then the third message is "Well, guess I'll come back and try this some other time". And then they don't. It is of course a misunderstanding of what a blog is. It is not a chat channel. Nobody might notice you right away, and if you really aren't saying anything interesting, nobody's going to bother. And it takes a while to build up a network of people who care about what you write, if you don't already have them handy (your friends and family).

But I must note also that it works a bit differently in the blog environment I live in. The blogging program I wrote was originally meant just as a feature in the New Civilization Network. Members can set up a hosted blog without needing any kind of technical knowledge about how it works. A couple of hundred people have set up blogs with that, and a fairly high percentage (for the blog world at large) of them are still active. But many of them are fairly unaware of that larger blog world and don't think much about it. And that is in part because the blog comes with instant readership and aggregation of all the local blogs. There are pros and cons in that, but basically the deal is that there are few enough blogs there that quite a few people comfortably can read all of the postings every day. And new people will right away get welcoming comments and encouragement, no matter what they wrote about, no matter whether it was terribly interesting or not. And if they haven't posted for a while, somebody might come along and encourage them to do so. So one doesn't feel alone at all. But that also carries the potential drawback with it that one doesn't get any further, and one thinks that IS per definition one's audience. And a certain group-think develops where one feels one has to fit into that group, or one complains about other people writing stuff that isn't kosher for that group, etc. Worries that normal bloggers don't have, because they generally start from scratch and then connect up only with the people they somehow are aligned with, and they don't worry about the rest.

There a parallel (to the question of why people stop blogging) in NCN in that an occasionally recurring discussion is "why do people leave and what can we do about it?". NCN was in some ways a forerunner for online social networks like Ryze or Orkut. It had many cool features before anybody else did, and still has stuff you don't normally see. But nowadays it also a bit dated and disorganized, and still has a look that was ok in 1995, but which isn't particularly contemporary now. Anyway, as opposed to more generic online networks, it has a theme or focus, even if it is a big and all-encompassing one. Basically it was meant for people who want to change the world. So, more than 9000 people have signed up over the years, and many of them thought it was a good thing at one point or another, but now there's probably not more than maybe 100 people who're active. So, some people worry about what happened to the rest of them. Why did they get scared away, how can we avoid it, etc. What is special here is that, even though they often are dissatisfied with something about the place, the people who are there have a certain attachment to it, and in the back of their mind some kind of hope that it could be more than just a place to hang out, so they care. Probably a lot more than Hotmail or ICQ cares that the vast majority of people who created an account have abandoned it.

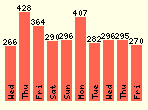

I can easily think of stickyness features for an online network site. Send people regular messages about how many people have looked at your profile, what messages are waiting for you, what postings are new, etc. And I need to finish implementing that for the network I did create. But, then, how about a stand-alone blog? Are there any personal sticyness features there? For my own blog, I have a graph of daily visitors in the side bar, a list of recent referrers (sites people came from), and a list of search engine searches that brought people there. There's the comments of course. And I religously watch Technorati or Bloglines to see who has linked to me. All of that is very motivating to keep posting. But only if you're already up and running and there's something worth visiting for others. If you just started a stand-alone blog and didn't post much, there will be no activity to make you motivated. There's of course aggregators. If your blog is associated with other people's feeds that you read, and a contact list, or blogroll, where you list other blogs your interested in, you'll keep being reminded of things to write about, and other people will find you, simply because they're mentioned by you.

Anyway, the answer might indeed be to bring more communication channels together in one place. If the blog is merely one integrated part of your interface to other people on the net, and there are many channels available, there doesn't have to be any stigma associated with not posting. You have to share *something* with *somebody* to be blogging, but what you share doesn't have to be some big article thing. It might be pictures, it might be your list of other websites, the feeds you're reading, the weather in your town, the books you're reading, the movies you've watched, or whatever. Not everything feels right for everybody all the time. So, if you have more channels of communication available, both incoming and outgoing, it is more likely that at least one of them will work for you.

[ Information | 2004-07-16 08:26 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

|

|

Al Qaida couldn't dream of a better government in the U.S. than George Bush's. They're a splendid help in the direction of destroying the United States, in providing plenty of new places to have terrorist bases, and plenty of new well-motivated recruits. And Bush could sure use another terrorist attack to boost his ratings. Quite some win-win synergy there. So, what do you say are the chances for that happening before November? Or, even better, around the election itself? Bush's people seem to be planning for just that. Cancel the election, declare a national state of emergency, and just stay on as a dictator. That's a great plan. Al Qaida couldn't dream of a better government in the U.S. than George Bush's. They're a splendid help in the direction of destroying the United States, in providing plenty of new places to have terrorist bases, and plenty of new well-motivated recruits. And Bush could sure use another terrorist attack to boost his ratings. Quite some win-win synergy there. So, what do you say are the chances for that happening before November? Or, even better, around the election itself? Bush's people seem to be planning for just that. Cancel the election, declare a national state of emergency, and just stay on as a dictator. That's a great plan.

It would be quite appropriate if the U.N. would monitor the U.S. elections, like a group of congress people proposed. The U.N. unfortunately said no. And the Bush government wouldn't have let them, of course. The system probably wouldn't stand up to any kind of organized scrutiny. You know, faulty voting machines without a paper trail, run by companies that support the Republican campaign. Plus the long list of other tricks and irregularities. The kind of stuff that Congress strikes from the record if somebody dares to mention it.

Anyway, just wanted to complain a bit. I'm no longer there, but the state of the U.S. unfortunately affects the rest of the world greatly.

Oh, and for something more to be freaked out about, Thomas mentions this story about a lady who believes she experienced a dry run for a terrorist attack on a plane, and the apparent inabilities for the system to respond well to that, because of rules for political correctness, etc. For example, an airline can't take aside more than two middle eastern people at a time, or they get big fines.

[ Politics | 2004-07-16 19:51 | | PermaLink ] More >

|

|

| Wednesday, July 7, 2004 |  |

|

|

|

I'm back from Blogtalk in Vienna. But let me just comment a bit on the second day. I'm back from Blogtalk in Vienna. But let me just comment a bit on the second day.